Tone Glow 035.5: The Hafler Trio

An interview with Andrew McKenzie of The Hafler Trio for a special midweek issue

The Hafler Trio

The Hafler Trio is a project spearheaded by Andrew McKenzie that began in 1982. While the collective originally featured McKenzie, Chris Watson, and someone referred to as Dr. Edward Moolenbeek, it has also featured and collaborated with numerous artists including Steven Stapleton of Nurse With Wound, Jóhann Jóhannsson, Autechre, and more. Joshua Minsoo Kim talked with McKenzie on September 26th, 2020 to discuss his childhood, the mysterious third member of the Hafler Trio, the artists who have influenced him, his time in Iceland, and more. All photos courtesy of McKenzie.

A note about this interview: Andrew McKenzie initially contacted me after my interview with Jim O’Rourke, wanting to see if I’d be interested in interviewing him. We initially discussed conducting an interview in a similar style, which involved picking 10 or so events or pieces of art that really impacted him and defined periods of his life. We decided to nix that and instead have a more straight-ahead conversation. Also: McKenzie is against his music being present on YouTube—which makes sense given what he talks about in this interview—so there will be none of the Hafler Trio’s music present throughout this interview. Thank you for understanding.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Hello?

Andrew McKenzie: Hello!

Hello! How are you Andrew?

I’m… reasonable! (laughs). Good day to you! Where are you in the world?

I’m near Chicago, in Illinois.

Near Chicago! Alright. It’s in the morning though, right?

Yeah, it’s 11AM right now, 11:10AM.

Alright! Well, as usual, with Skype you have to check whether it all works. It’s not like an old fashioned telephone which immediately does work. As technology “improves,” we have to check it even more than we used to.

Right, that’s the irony of it.

So, I don’t know how you wish to proceed, but let us proceed!

Yes! I’m planning to make this rather casual, that’s the way I tend to work.

Sure!

Before we start: How has your day been?

My day? Well, at the moment we’re sort of having what they call an Indian summer. My body doesn’t like the weather going backwards and forwards. My stomach, and a large part of the rest of me, doesn’t like this air pressure stuff changing rapidly, so I don’t enjoy this very much. On a more general note, this country got off quite lightly compared to many other countries with regards to the virus thing. It does look as if that might be taking another turn for the worse, but it doesn’t really affect me very much—I almost never go out (laughter). I’m not a socializer, so I just plod on basically. That’s really what I do. I’m a slow learner—I’m slow at most things—but I’m persistent! Or, the more negative side of that particular coin, I’m stubborn! (laughter). It depends on which way you want to look at it, really.

I mean, persistence is always going to be important regardless. I think that trait always trumps whether or not one perceives themself as stupid, or a slow learner. I think there’s a beauty to that process of going slowly, rather than just picking up things and going, “Okay, I get it.”

It is definitely a thread that runs through a lot of what I’ve been interested in. There’s things that take time to unfold, and they aren’t instant. You know, the old joke—well, it’s not that old—the more recent joke about instant not being fast enough anymore, especially in the United States. All the things I’ve ever wanted to make—or ever was interested in listening to, or reading, or watching, or getting involved with—were things that did take a lot of time to unpack, or to reveal themselves, or to make themselves known. And you could go back to them again, and again, and again, and still see or hear or experience new things. I think a large part of that is sort of lost now.

I do notice that because there is so much stuff, people don’t have the patience anymore. If it doesn’t yield any kind of benefit, people pass on to the next thing, which is a bit easier to digest. That’s kind of 180 degrees from how it was when I first started getting interested in these weird things, just because they were difficult to work out and they did take a lot of effort, and they weren’t easy to digest. So it seems to have gone, even with the more avant-garde people—in a lot of cases, they seem to simplify things in order to sell it. Again, maybe I’m just out of step with absolutely everybody else, but it does baffle me. There’s a place for the instant, but if you really want to go deep into something, it has to be something that was created in that way; you have to match the effort of the creator, the audience has to match the effort of the creator. And if the creator didn’t put that much effort into it, then the chances are—it’s not impossible—but chances are you’re not gonna get that much back anyway!

It’s a weird situation because I’m of an age now where I do remember when we didn’t live in a karaoke society. This idea that you’re supposed to be able to sing along with everything now; you come across a piece of art or music and you think, “Oh yes, well I can do that as well, if only I had the software and I knew exactly how they did this.” When I was first getting into these things, you’d value things because they were unique and uncopyable. Now, if you can’t be copied, you don’t end up on anybody's radar. It’s a really strange, diametrically opposed situation, as far as I’m concerned.

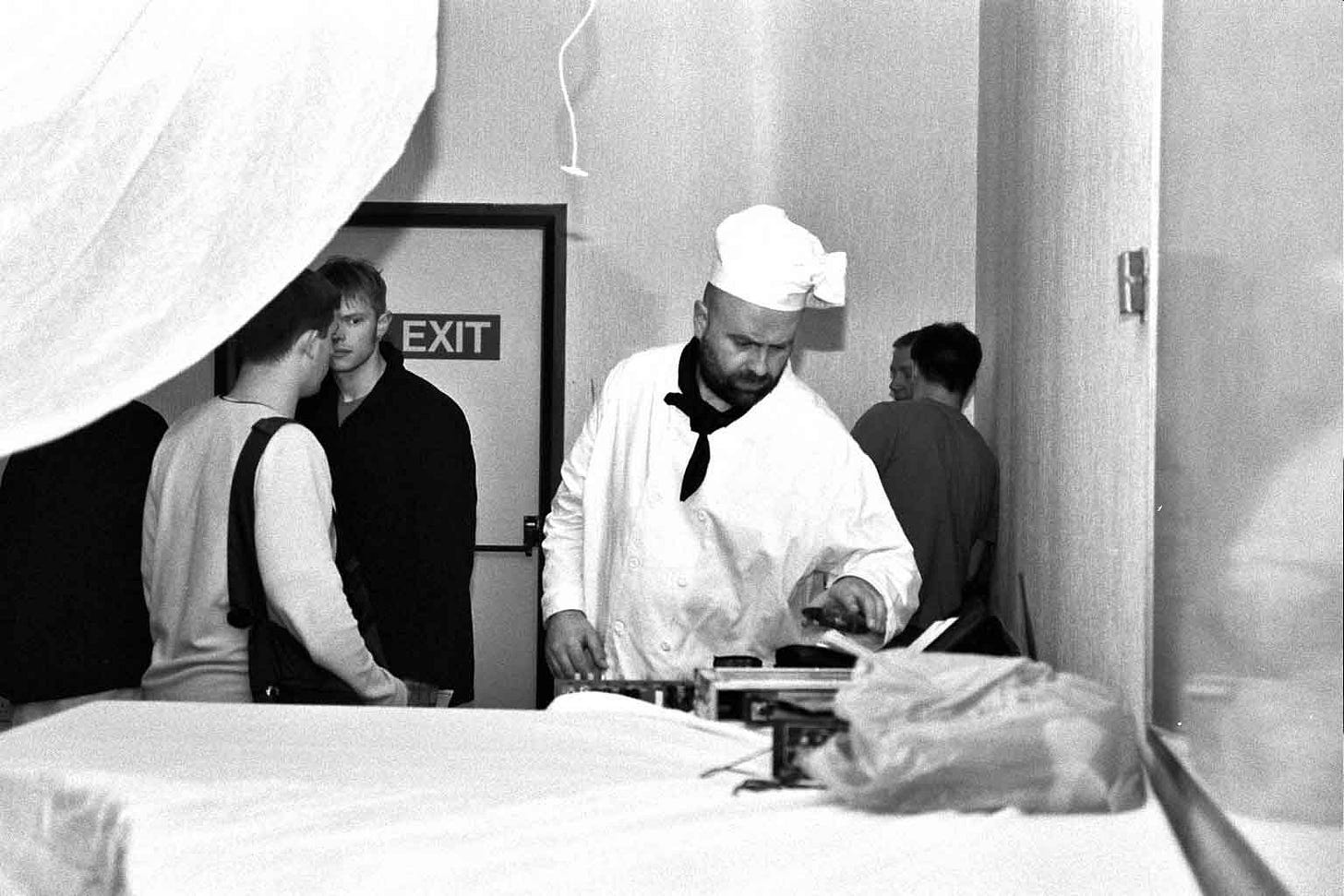

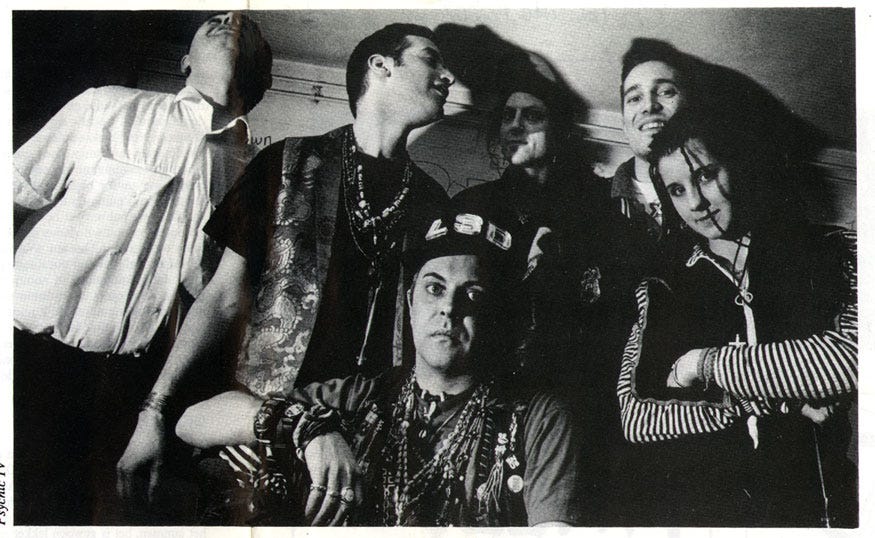

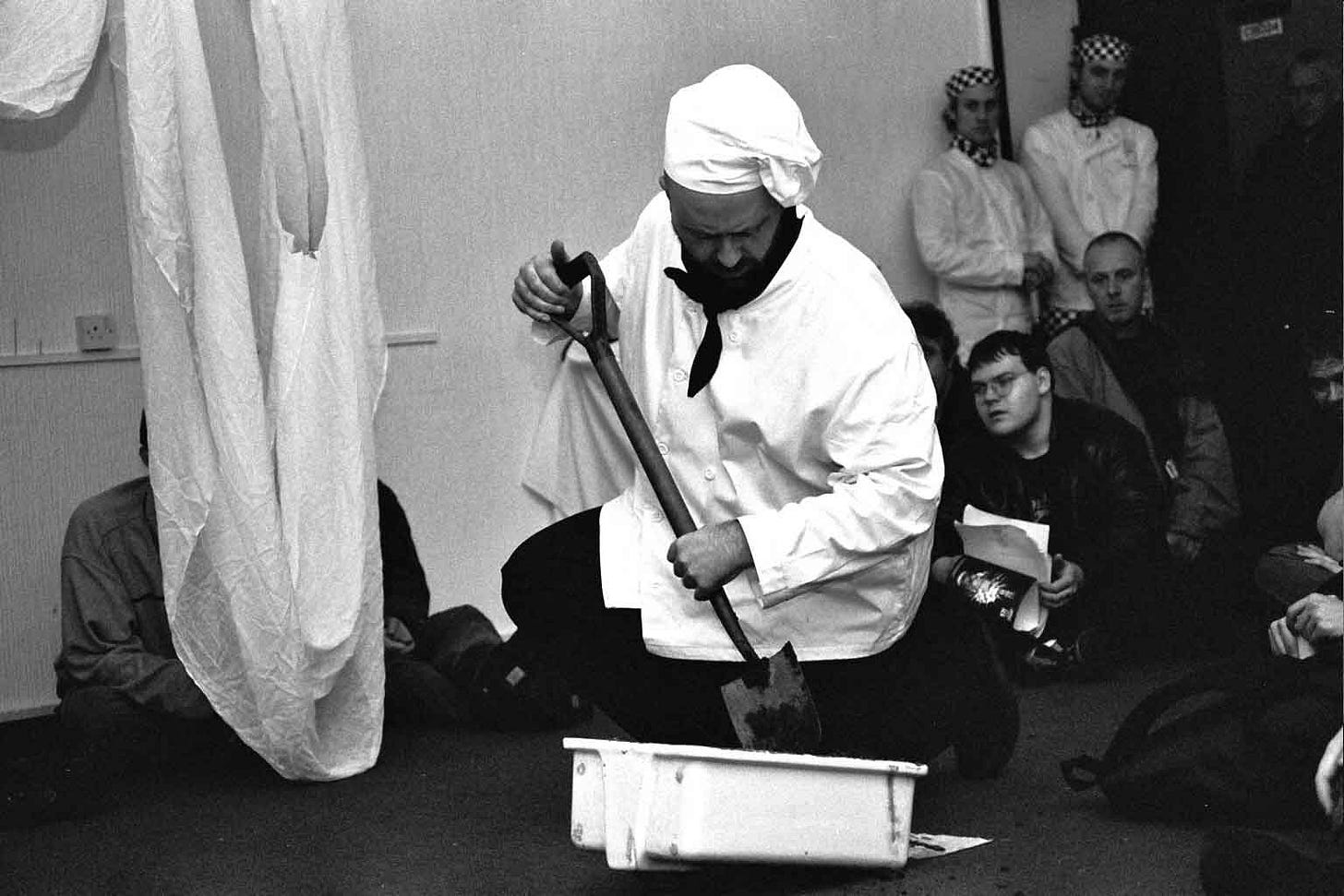

McKenzie back stage at CBGB

From my end, as someone who’s interacting with press folks regularly, it feels very much that if you aren’t in this ecosystem, you’re just going to get ignored completely.

Absolutely! Yes, very much so! I’ve never been a joiner, I’ve never been anybody that wanted to be a part of these cliques and groups and stuff. Now it seems even more that, like you just said, you don’t exist really unless you’re part of these things, if you’re not constantly sticking your two cents into this situation or that situation. It’s baffling to me, but it’s always baffled me—this herd mentality of wanting to be part of these groups and stuff. Even when I was a kid, I never really understood this whole thing; I never wanted to be in a football team and I was never interested in those kinds of things.

So what were you like as a child? You were born in Scotland, how shortly after did you move to Newcastle?

Very, very soon afterwards.

Do you have any memories of growing up in Newcastle? Is there anything that feels emblematic of having grown up there? Any memories with your family or anything? I’m just trying to get a picture of who you are, your surroundings, your family.

My mother worked at a library for most of her life, so I kind of grew up in a library. My father was a policeman, but in those days, a policemen were—as he described it—society’s rat catchers. They were paid nothing in those days. I can actually remember my mother having to sell her clothes in order to buy me and my sister shoes. These days, they have to pay policemen in England and a lot of other places a reasonable wage, otherwise they wouldn’t do it, but in those days it wasn’t like that. It was very tough. My sister and I used to think that Santa Claus was the guy in the police uniform who would sleep on the sofa on Christmas morning.

[My father] would have been a really good criminal because he thought like that, but his father forced him to become a policeman or else he would have thrown him out of the house. So he was an excellent policeman because he had a mind like a criminal!

What do you mean by having a mind like a criminal? Is there anything that comes to mind that reinforces that idea for you, that made you realize that when you were a child?

You have to think in very odd ways to be a really good criminal. You have to see solutions to situations that other people don’t see. You have to find your way around barriers that other people can’t find their way around. That flexibility of mind is really what I’m talking about. He never got far in the police because he wouldn’t join the Masons. At that time in the British police force you would have had to become a Freemason—that’s changed now, I believe—but he wouldn’t. So they kept on trying to make him quit by putting him into the worst possible jobs. It didn’t work (laughter).

He eventually became a playwright and wrote for the television and radio and theater, and is still doing it as far as I know.

What’s his name?

His name is Arthur. Arthur McKenzie.

Awesome. You sent me a list of music that influenced you, that inspired you. What was the earliest piece of music that really sparked your curiosity that you would also consider to be relatively challenging? How did you come upon that?

Now I have to run around some definitions of challenging! The radio was on a lot in the house while I grew up. We’re talking about… I was born in ’63, so the middle-to-late ’60s. We’re talking about a period where England changed over from being black-and-white into color (laughter). I mean, it really was like that. It really was! When I was a child, everybody wore brown or grey, and it was the north-east of England, which was grey. People still burned coal, so there was a lot of pollution and smog and all this other kind of stuff.

Suddenly in the ’60s… color! It was literally like, in those days color televisions were quite rare, and when one arrived in the street, everybody on the entire street would go have a look at it. It really was like that! I grew up with the same stuff that was on the radio, nothing too challenging of course. That was British radio, and of course they wouldn’t play anything really extreme.

My father, being a policeman, had to interact with some of this stuff. He had to be part of a bodyguard team for The Beatles. He locked up The Rolling Stones one day because they trashed a hotel room and he had to arrest them. The ’60s was happening, and I was a bit too young to take part in it, but by that time I was beginning to become aware of stuff. My grandmother on my mother's side would come every weekend, and when my sister was old enough she would come as well—[my sister] was three years younger than me—and we would be taken out. There was a regimented order to the day, and at a certain point we would be given a small amount of money and we could actually decide what we wanted to spend it on.

The first record I ever bought was by Spike Jones. It was a 7-inch single called “You Always Hurt The One You Love”, and the other side had “Cocktails for Two” on it. I don’t know why [I bought it]—I cannot actually tell you why—it must have been suggested to me. I must have had some sort of proclivity for odd things because it is an extremely odd record, even today. But I didn’t think it was odd! I just thought it was interesting. I remember thinking his formula was to play the original standard, the original popular song, and then just completely explode it and destroy it and mangle it. I thought this was a perfectly reasonable thing to do! (laughter). I didn’t see anything weird about that at all!

Coupled with that—I didn’t hear them the first time ‘round, I’m not that old—there was a radio series called The Goon Show which had been very popular and had been repeated every four or five years on the radio. This—you will find, if you go looking—was basically the genesis of all of the surreal English humor that everybody knows in the form of Monty Python, or anything like this. It was audio surrealism! If you listen to it today, some of it’s dated, but some of it you just can’t believe what you’re hearing. It’s just so bizarre. It was just part of the air that I was breathing. If you listen to it, it’s just impossible, the sound effects and the situations and stuff would only be possible on the radio. You’d never be able to do it on a screen, it would just be impossible.

There’s a very memorable moment where one of the characters is in Scotland and he wants to get somewhere, so he calls a taxi, but the taxi is actually just some bagpipes. The bagpipes actually draw up, and you hear the bagpipe motor running and they take off, and there’s a sort of Doppler effect. You get into a set of bagpipes and you just drive off! Stuff like that. I came across surrealism later on. Actually, it’s been fairly tame compared to this kind of stuff, which was genuinely anarchic in the best sense of the word.

As to challenging: in those days there was such a thing called a radiogramme. A radiogramme was basically a piece of furniture which would have a radio in it, and a record player. It wasn’t meant to be a piece of high-tech, it was actually a piece of furniture. It was in mono, and it had one large speaker, but it was just a walnut cabinet. On the left and right side there was a cupboard where you could put LP records towards each other. When you opened the top—there was a lid that you lifted—there was the record player. When my parents bought it second hand, there were a bunch of records in it already. One of them was The Beatles double White Album in mono, which is different from the stereo version—there are different endings to certain tracks and stuff. When I heard the stereo versions eventually, I was really shocked because they had all sorts of stuff that I wasn’t used to. That must have been when I was about six, because it came out in about ’68. It must have been around that time.

There were a few other things; my father won a record in a radio competition. Or, he won a record voucher, actually. He went off to this record shop and bought a record by a woman called Diana Dors. [My Mother nearly killed him] Diana Dors was the cheap, slutty version of Marilyn Monroe in Britain. She actually made a record with the superb title Swingin’ Dors. It was the very first colored vinyl record—bright red. So there was that, and there was Johnny Mathis’s Greatest Hits. We also had a record of classical guitar, and that’s what started me off on that.

What was that record?

It was a compilation of short-ish pieces of different composers played by Andrés Segovia, who was considered one of the world's greatest guitar players. A few years later that made me want to start playing classical guitar, and I did. I ended up becoming a guitar teacher. So there was all that being mixed in.

The thing was, there were so many things happening at that time. When you originally asked me to [email] you ten [pieces of art that influenced me], there were too many of them all mixed together, and they all lead into each other. So you have a situation where you have The Beatles double White Album, and of course I’ve tried to play along with it, and work it out, but of course you’ve got “Revolution 9” at the end of the fourth side, which is a tape collage! They all bleed into each other, and they all influence each other.

So the first one, this Spike Jones record. For many years I had no idea what he looked like. In America in the ’50s there was a television show that he had. A lot of Americans actually grew up and they knew what he looked like, but I had no idea what he looked like. I remember the shock from seeing him, that he actually looked as outrageous as he sounded!

Right! He has a cartoonish face.

It’s bizarre! And those suits, and the rest of his band: they are cartoon characters, living cartoon characters! I was very pleasantly surprised that it wasn’t just a bunch of ordinary looking chaps making weird stuff. I mean, they lived it!

When did you start playing guitar?

My father was an athlete, as well as being a policeman. He—unusually for that time—actually had a passport. He actually left the country—British people are notorious for not going to other countries because, of course, (mockingly) they’re foreign. But he used to go to these athletics meetings in various countries. He was in the Commonwealth Games and won a lot of medals and all this for the discus and the shot put and the hammer, and weight lifting as well. All his friends looked like Michelin men (laughter).

One time, he went to Spain and he came back with a guitar as a kind of souvenir. It wasn’t meant to be played, it was meant to be hung on the wall to demonstrate that you’ve been to Spain. I put fishing line on this thing and started twiddling around with it. Eventually my parents got the message and as a Christmas present I got… I think it was six guitar lessons at a music shop in the center of the town. This guy gave six lessons, and I went through these lessons very quickly. It looked like I was getting serious about it, and then I had private lessons, which was quite unusual at that time because any interest in art or music meant you were gay in the old days—if you were playing classical guitar you had to grow your right finger nails long, which didn’t help. This was the era of the Northern English skinhead. Things were a bit violent, shall we say.

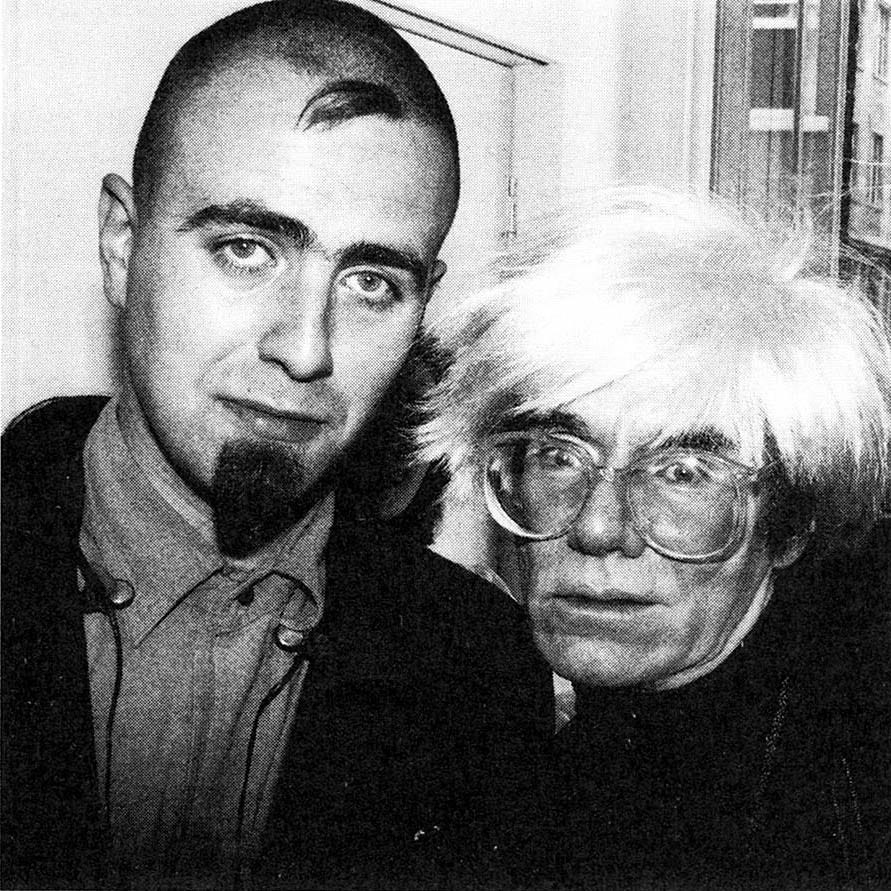

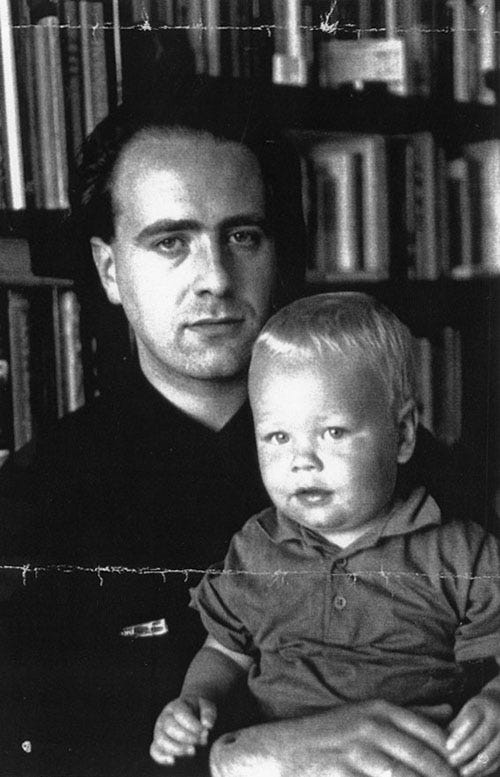

McKenzie and Andy Warhol

How old were you when you got the lessons and the guitar?

The lessons started when I was either ten or eleven, I don’t remember. More likely to be eleven. I qualified and passed these exams and stuff when I was twelve. I was also very tall for my age. When I was twelve I was the height I am now, which is 6’ 1½”. This also meant that in school I got the job of playing double bass because nobody else could do it, nobody else had big enough hands (laughter). I ended up being able to play most of the instruments in the orchestra to some level because they were just lying around and actually people weren’t that interested. I used to not take the school lunch, and I would be locked up in the music room and I would basically learn to play these things, because nobody else was interested. I would listen to classical music and the music teacher was so happy that somebody was actually interested in this kind of stuff.

Would you say that you were the only person doing this? You had no other classmates that you could commiserate with in regards to playing and talking about music?

For a while, yes. Certainly [in regards to] playing, for a long time. There was one other kid who I was friendly with—one of just a few other kids, I was always kind of a loner. His father was an artist, which was, to use an old phrase, as rare as rocking horse shit (laughter). These were very bizarre animals, not seen in the northeast of England in the late ’60s, early ’70s. He was a Scottish guy and he had two sons and a daughter. I became very friendly with the middle kid, which meant I used to be able to go to this place. They were very progressive—they allowed their kids to smoke and swear and have girlfriends and all this other kind of stuff. Of course, this was heaven as far as I was concerned. There were some weird records around as well. This is where I first heard some of the formative things, because they were just lying around. We made a little pact: we would save up money and buy a record every three or four weeks. We would wash cars, and do stuff like this to earn money and we would buy these records together.

Do you remember your friend’s name?

Stephen Park. His father was called Alistair Park. He had been a friend of Ivor Cutler’s, if you know who he was. He once read us a bedtime story.

What the heck? That’s so random!

(laughs). I didn’t know who he was! I did later on, obviously.

Stephen was a big drawer. He used to draw all the time. We used to listen to stuff very intensely. If you bought a record then, you memorized every square centimeter of the cover. If there were words, you would know those words. You’d listen to nothing else but that record for two weeks straight. If you were awake, you were listening to that record. That level of change that could be brought about by one of those records… you would just never be the same again because you would be able to go into it at a level—for better or for worse—that I don’t see happening very much today.

With the scarcity of records that one would have at their disposal, it forced a closer engagement.

And you value them more because they’re almost impossible to get. You couldn’t afford to go and buy 20 at once, you bought one every month, if that.

What were some of the records that you remember you and Stephen purchasing and listening to and really cherishing?

His older brother Laurence was a bit more advanced. He liked rock music, like straight-ahead rock music. But he had some slightly odd tendencies, and those would filter down. So Stephen would borrow one of these slightly more odd records. Laurence was a big Free fan. I never liked this sort of white men playing the blues thing, I’ve always detested it. I think the first one was a Van Der Graaf Generator record.

I think that was the first record. Downstairs in the living room in the same house I vividly remember the Fripp & Eno record Evening Star. I remember this very vividly because the cover was like nothing else I’d ever seen before. I had bought (No Pussyfooting), but I was very disappointed because it was basically just two long guitar solos, and I just wasn’t very interested in that. The second side of Evening Star… the first side has some wonderful things on it, but the second side, which is just one track, is this thing called “An Index of Metals”. This sounded like it was literally from another world. I had absolutely no idea how this was made and how this was possible. It felt like being at home! It was totally like nothing else.

The Van Der Graaf Generator stuff of course, it wasn’t the blues stuff, and it wasn’t the awful prog-rock stuff that was so prevalent at that time. It had some sort of link to it, but there were no great long drum solos or, “Look at me! I spent 20 years in the conservatory and this is what I can do on the keyboard.” There was nothing like that. It was really tight, and it was nasty, and it had all sorts of philosophical ideas it borrowed from. There were references in the lyrics to the Eddas and to philosophers and all this different kind of stuff.

If you want to make a thread—it’s always easy to make these things in retrospect—any of these things that I was very interested in, they always have references to other things. They are never self-contained. With this Evening Star record, there’s all these references: there’s the Peter Schmidt painting on the front, and then you’ve got this whole idea of cybernetics, which is part and parcel of the modus operandi of Mr. Eno there, and you’ve got references to all sorts of other things. All of these things which I ended up being interested in, they weren’t just a jolly tune; they were always referring to what we would later on refer to as multimedia, with references to film or literature or philosophy or whatever. It just became something that you did. But in those days, if you were a musician, that’s just what you were. You weren’t expected to make any references, but all the greatest ones really were doing that.

The first Van Der Graaf record I’d heard was Pawn Hearts, which was a hell of a way to come into it. It’s like psychotherapy or something. Even today, it’s pretty heavy stuff. It doesn’t seem to come from any other tradition, it comes from tinges of this or that or whatever, but it really seemed to come out of nowhere, and it’s pretty impossible to copy as well. That record, I mean, I could probably do the whole thing for you right now.

Around this time—and I only know this from looking at your Wikipedia page—you released a 7-inch when you were 14 with a group named Flesh. Can you talk to me about that? Who was in Flesh and what was that music like?

(laughs). This was myself and a lovely man named George Handleigh. He was a small guitarist who was a lot older than me. I met him because I was babysitting for a guy who worked for Arista and Chrysalis Records. I used to get a lot of free records as long as they were on Arista or Chrysalis. They had three children, and they would go out and leave me with these three children and [I was on] piles and piles of drugs. They could come back and the kids could have been murdered, I wouldn’t have known (laughter). So I got all the drugs out of the way very early.

I met George, who was a friend of a friend of his. We just hit it off. He used to play guitar very much just like Robert Fripp. This was a very big plus in my book because, again, it wasn’t just the usual sort of blues stuff. This was ’77 or ’78 I think, something like that. I was never really a punk because I thought that most of the punk stuff was basically just heavy metal but played not even much faster. I found other things far more disturbing and antiauthoritarian than the rest of it. Obviously [I like] some of it, yes, but I remember being bitterly disappointed—I bought The Sex Pistols’s Anarchy in the U.K. on what I think was the day it came out. The same day I bought The Sex Pistols single, I saw hanging above the record store’s counter The Residents’s Duck Stab! EP. This was a far more anarchic and a far more mindblowing record than any Sex Pistols record, as far as I’m concerned.

That’s so true. It’s funny—growing up I heard so many things about punk music and I remember the first time that I heard The Sex Pistols’s Never Mind The Bollocks I hated it! It was absolutely nothing like I thought it would be in terms of the intensity and the energy, and what I thought punk music was gonna be. It was so tame! It’s nice to know that you had this experience when the music was coming out. It’s so funny that The Residents are the group juxtaposing The Sex Pistols in this case.

I just thought that—it was shrink wrapped, it was an EP, and it had a fold out sleeve—it was a 7-inch. I had no idea what was on the inside of it or whatever, but I saw this thing. It was quite expensive because it was an import. I actually bought it, and I remember putting it on after the Sex Pistols thing and I thought, “...my God!” I don’t think I ever recovered from it! I think it’s amazing music, an amazing piece of work.

Anyways, we were interested in the mavericks of what was available at that time. There was a lot of changing going on because of the punk thing, so maybe the music wasn’t the most important thing anyway. So we formed a group and we didn’t feel like we wanted to have anybody else. I’ve been experimenting since I was a kid with broken cassette tape recorders. I didn’t think anybody in the world did this, but it turns out years later, there were lots of people doing it! How was I going to know?

We made these backing tapes, which were just these sped-up, slowed-down, looped crazy stuff. The two of us would just stand there, I would be wearing clothes that I got from a secondhand shop, which were like old mens’ suits. I would stand there and say the first thing that basically came into my head. People hated us. We were actually held up as a standard of how bad things could actually be.

There was an alternative record shop in Newcastle. Associated with that record shop was a drug dealer who had this money that he wanted to get rid of. So they thought, “Okay, we’ll start a record label,” because there were all these independent record labels starting up at the time, and everybody wanted to be the new Factory or the new whatever. Somehow—and I don’t know to this day why—they said, “Okay, well, you two do something.”

So we went off to a recording studio, which was actually a four-track run by an ex-policeman who was also a dope dealer—maybe that’s why he was an ex-policeman, I don’t know. We made this record, (fond reminiscent laughter), which was a version of Millie Small’s “My Boy Lollipop,” but slowed down and with nasty lyrics and a strange original thing on the other side of it. They pressed it, but I think it only sold like ten copies. It didn’t fit into any [genre]. It wasn’t a rock record, it wasn’t a punk record, God only knows what it was.

We did a few concerts. We did a support of The Clash of all things. When The Clash were on tour in the U.K. at that time—basically any time they played—there was a full scale riot. At that time, to show your appreciation for a group, you spat on them. So you would come out completely covered in human spit. They were throwing pints of beer at us, and we take that as a compliment in Newcastle in 1978 or ’9. But yeah, we supported The Clash because the bass player [Paul Simonon] really liked the single for some strange reason. I don’t know why, I can’t make this stuff up.

We also supported The Fall and Cabaret Voltaire, which is how I met Cabaret Voltaire for the first time. Of course that became important later on because of Chris Watson. There were such a small amount of people involved in doing anything like this. There were so few people. We kept in touch via the postal service, but many times you’d be writing to someone for some years who you didn’t even know what they looked like. I grew up in Newcastle and from the age of 14 I was friendly with Ben Ponton, later from Zoviet France. We did all sorts of recordings together. He had a punk group with some other people and I joined. We made all sorts of experimental tapes from a broken reel-to-reel tape recorder in his bedroom. We listened to John Peel on the radio, which was the only place you could really hear anything new, even vaguely.

This is all very exciting for me to learn! I feel like I’ve had no idea about anything in your life prior to the Hafler Trio. It’s cool hearing all these things that led to you and Chris Watson eventually making that first record. How did you and Chris decide on making music? How did you two come together? Was there something about him that made you want to work with him in this sort of context?

Well what happened was that very shortly after, I was doing these concerts with George, and through this guy that I babysat for, I got a job at Virgin Records, which was a record store in what Americans would call a shopping mall.

You were working the shrink wrap machine, I remember reading that!

I did indeed, and I’m sure that had a lovely effect on my lungs! (laughter). A lot of things came out of that because in those days that was how you got your information about music. There were three main music papers, Melody Maker, New Music Express, and something called Sounds. I don’t think any of them exist anymore. This is how you got your information. Also by hanging around in a record shop and hoping. That was what you did! And I ended up working there.

Eventually I got Ben a job there as well. We were actually working in the same place. That allowed me to hear all sorts of records and buy records at staff discounts that nobody else could get, because I could actually order these things that the shop would normally not even order and put in the racks. I, and later on Ben, were able to get these things. We were responsible for introducing a whole bunch of people to weird things that perhaps would not have come in. David Tibet, for example, was a regular who would come in trying to get free or cheap records. It was me that suggested that he listen to Nurse With Wound! So that’s actually where he learned about Nurse With Wound. That resulted in—well, you can see what happened later with that. He was living in a place called Benwell, and he was a student at Newcastle University. He used to come into the shop—the thing I remember most about him is that he had the worst breath I’ve ever, ever come across (laughter).

This was David Tibet?

Yes! I have no idea what he was doing, he must have been eating musk-oxes or something. It was just horrible. He lived in a series of appalling squats all over Newcastle, and then in London when he moved out there. He sold me a bass guitar once, which I’m sure was stolen. He was always trying to get something free, or cheap—so was everybody else, of course. He was mad keen about Throbbing Gristle, but I think I also introduced him to Whitehouse along with Nurse With Wound and a few other things.

He wrote a fanzine. In those days you could go to a photocopy shop and you could run off ten copies and you sold them for almost nothing. He did one about Charles Manson. As far as I remember, he wrote his university thesis on why The Third Reich were the greatest performance artists of all time.

Ah jeez, god. Of course.

Of course! A lot of people were doing that kind of stuff. A lot of people were flirting with that kind of stuff at the time. It was part of the whole rebellion thing. I have no idea what they were talking about. It was very common.

Newcastle never really had a scene like Manchester did, or Liverpool did, or any of those kinds of things. There were just a few people doing this kind of strange stuff, it wasn’t much. Not long before I left the Virgin Records job, Chris [Watson] moved up to Newcastle from Sheffield. He’d split off from the whole Cabaret Voltaire thing and he was really sick of the record industry. He had some bad experiences, and this and that. He was working as a sound recordist. He got a job at Tyne Tees Television, which was the local TV station. He had a part time gig which he was also doing for something called the RSPB, which is the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. His job there was to basically jet around the world recording the last squawk of a particular bird that was about to disappear off the earth. That was his sound job.

He came into Virgin Records one day. I hadn’t seen him for a very long time. I kept in touch a little bit with the other Cabaret Voltaire people. I went around to where he was living, and very reluctantly we started doing this strange stuff. That’s basically what happened. He was a very suspicious person about everything, basically. I think he had a very bad time with the whole end of Cabaret Voltaire, and the dealings with Rough Trade and things like that. I don’t know all the details, so it would be wrong for me to say. He definitely did not have a good attitude towards us. He didn’t want to do records anymore. We were gonna make radio plays. This was the big thing.

We were both mad keen radio fanatics. I’d been co-owner of a food shop and used to have Radio 4—at that time there were four radio stations, this was BBC radio. They used to have documentaries, and I used to record these weird bits of documentaries about Welsh housewives having too many pumpkins (laughter), and you know, all this great stuff. This was long before the internet, long before there was access to all this weird stuff. There was a particular manner that they had on Radio 4. It was not quite condescending, but well on the way to being that. It was a very old-fashioned kind of genteel, and this is what we were trying to emulate.

These were the days of the cassette magazine. There was a cassette magazine called Morrocci Klung! run by a guy called Rob Pierce. He also had—which was also quite popular at the time, and highly illegal—a pirate radio station in London. Richard Kirk from Cabaret Voltaire had already given him an hour long program for this. It was Richard, who Chris was still very friendly with, who asked if we wanted to do one. Chris said, “Oh, no no no no no,” and I said, “We could use all this mad stuff we’ve been doing and we could put this on there!”

So we gathered it all together, and of course that meant we had to think of a name. That’s how all that came about, which is worthy of a book in itself. That’s basically how it went up. But there was never any intention to make the record. That only happened because later on—about a year later I think it was—Doublevision records came to be. It was also me pressuring him. I think it was Richard who just kept on and on and on at him saying, “Look, we need stuff to put out on this label. Why can’t we put them out?” So then we re-edited it and came up with all the other stuff. But it wasn’t intended, the first thing that did come out was this radio thing. The interesting thing about it was that in those days very few people had cassette recorders hooked up to their radios. It was just a one time thing, it would be on the radio, and there it was, and then it was gone. That was actually the nice part about it, it was just one of those things that would be on. You might turn the radio on and there’d just be this strange thing—you’d have no idea what it was. That was the whole idea. The fact that it was on a pirate radio station—the fact that people would only bump into it by accident was also a nice thing.

It heightens the experience. It makes it feel even more serendipitous and it makes the oddity of what you’re hearing even more odd. It feels like you’re listening in to something secret, or private.

Yeah. We both really liked the sound of the radio, the way that—when you broadcast something on the radio—it gets compressed in a certain way. Good radio has a kind of warmth that comes to it that you don’t get so much with other systems. It was a really, really nice medium. The fact that it was flying through the air (laughter), not through wires and all this kind of stuff, this was also very nice.

We both listened to a lot of shortwave radio. That culture has pretty much completely died now. These stations that you would find, and you would tune in and it would be half way—it wouldn’t be a complete signal. It would drift off, and you’d hear these exotic voices and you’d have no idea what they were talking about. There was all this interference and beautiful distortions and all this other kind of stuff.

Again, it didn’t start off being like, “Let’s get together and make a record.” We were both interested in these more… esoteric recording practices, shall we call them? [Chris] had access to all this high-tech stuff with working at the television studio. On a famous occasion he actually used The Rolling Stones’ 32-track mobile when they weren’t using it! (laughter). Stuff like that happened. He would be able to rent boxes that did strange things and we would process a whole bunch of stuff before anybody else knew what was going on, and we would use it later on.

On one wonderful occasion we actually rented a thing called a Quantec Room Simulator. It’s this amazing box—I’m not sure you can even get them now. What it did was, you could punch in some coordinates and materials and it would give you the acoustics of that. One of the presets was the Taj Mahal, another one was a match box! There was everything in between. We rented this, I think it was £150 for one weekend, which was an enormous sum of money then. We rented this thing, and I remember that I sat and put through many, many, many recordings through this machine, and then re-recorded them. That ended up being used, pretty much all of that got used on various projects.

The funny thing was that this machine, there were so few of them and they were so expensive—this machine had come from a recording studio, and it had been used by Wham! for “Last Christmas.” It was the sleigh bells—sleigh bells had been put through this machine. Every Christmas everyone always plays this record and every time I hear it I remember that there is a link between me and Wham!’s “Last Christmas.” A particularly bizarre association. So there we are (laughter). You never know! Like we talked about before—all these things you never really know. There are lots of people who say they planned this or they have a nice chronological order, but you could never plan that! (laughter).

What was the reason behind the name of the group? And what was the name behind the fictional character Edward Moolenbeek?

He wasn’t fictional, and he was fictional at the same time. Without going too much into detail: we originally were not going to be called the Hafler Trio. There was a magazine called Studio Sound, which was for professional recording studios and people who worked in them. Chris was subscribed to it—you got it free if you were a registered sound person. I wasn’t, but he was. He used to get it sent to him every month.

The day we went to master the LP, there was an article about David Hafler in it. The three speaker system he invented—he also invented a four speaker system—which uses outer phase information from a stereo signal from the third speaker, and the third speaker is connected to the positive terminals of both the left and right speakers, but not to the negative terminals. You get all the out-of-phase phase information. You can actually stand in the middle of this triangle and it would be equidistant. You would also hear new things—on records that you know very well you would actually hear new things come out of it. Eno had put this on either Discreet Music or Music for Airports, I can’t remember which one. He actually itemized this, but it was actually invented by a man named David Hafler. David Hafler’s main business was that he made kits of very high-end hi-fi equipment but it was cheap because you’d have to make it yourself. In the world of hi-fi you could pay as much as a house for an amplifier, but in his world you could buy a kit for a fraction of that price. They still exist, I believe—Hafler amplifiers and other things I think still exist.

But it was the Hafler Trio—we couldn’t call it the Hafler Duo.

Wait, why not?

Because it sounded wrong! (laughter). Oh, I don't remember why. So we came up with that, and we thought, okay, we want to squeeze as many influences [in], and these were the days where many people were starting to refer to themselves as researchers. They had broken tape recorders but they called themselves “researchers,” they weren’t messing around just like everybody else. This sort of, “We aren’t really musicians, we are Scientists!” We thought, well let’s take this to its logical conclusion.

Just like a novelist, we made a composite of our favorite people of that time into a person. On the insert of the LP, it says, “All material by the Hafler Trio.” So there’s no excuse for being taken in by, “Oh, but it’s not real!” Well, complain to a novelist then! It’s not real, no, but it contains truth. All the great novels contain truth, even though they are not literally true.

Edward Moolenbeek was actually a composite of several people—real people! He was in fact a real person, except he just didn’t have that name. It was a friend of Chris’s and later became a great friend of mine called Alan Cook. Alan was a born surrealist, or dadaist, or a combination of both. He was never, ever doing it to be recognized as such. He just was that way. He had been a fireman—he got thrown out of being a fireman because he stole all of the instruction slides that they use to demonstrate and show people what different kinds of fires were like. They [Cabaret Voltaire] used to use them as backdrops for their shows.

His father’s attic was actually where Cabaret Voltaire used to rehearse and make tapes and stuff like that. Alan is the great unsung hero of this thing. Then he became a policeman, and he got thrown out of the police force because he was caught photocopying books by Wilhelm Reich on the police photocopier. He built a scale model of the Great Pyramid of Giza in his back garden. He then became a private detective, and that bored him so much. He thought, “What do I like doing more than anything else in the world? Ah, drinking! Okay!” So he set up a homebrew shop, where you could buy supplies for making your own beer and wine and all the rest of it. He used to brew large quantities of beer and wine in big plastic garbage cans. He said he knew the end had come when a man came in and complained saying, “I bought this set from you the other day and the pipette is broken.” Alan was a big man, and he took off the lid of one of these garbage cans and stuck his head into whatever it was—beer or wine or whatever. When he eventually came out, the man had gone. He said he knew that the end had come.

He then became a counselor for troubled youth. Instead of—as was very popular in those days—treating them with kid gloves, saying, “Oh, you’re from a poor disadvantaged background,” he used to say, (in thick Sheffield accent) “I’ll fuckin’ kill ya if you misbehave again!” And it always worked (laughter).

Unfortunately I lost contact with him for a very long time. But he was a real person. He embodied the spirit of all of these things. But he never did it, he never made records, he never made art—he was just like that. He’s on several Hafler Trio records, he’s responsible for a lot of ideas. His voice and his writings are all over the place. [Moolenbeek]’s basically an amalgam of all of these people we have respected and admired at the time rolled up into one person. You can say he didn’t exist, but he did! There’s always been all this confusion but it’s actually just as valid as anybody inventing or using a whole bunch of people to create a new person, which is just as real. If you want to write about somebody but you can’t use their real name, you just describe them and change the guilty party’s names.

We live in a situation now where truth and untruth—we were dealing with that [back then], the first release on many levels is addressing this quite important problem, or situation, or whatever you want to call it. It’s just become more relevant as time has gone on.

What sort of ideas do you feel like Alan brought to the Hafler Trio that you feel like wouldn’t have been in there otherwise?

I still have a folder full of letters [from Alan]. These are high art. Nobody else is going to see them, and he spent ages and ages writing them. They’re insane, beautifully, wonderfully insane letters. I’m not a small man, but he was a lot bigger—he must have made quite a policeman, I tell you. When he walked into a shop, the room got dark, basically. We were walking along the street in Sheffield one day and we were talking about some sort of nonsense and he just said, “Wait a minute.” He just walked across and opened the door of the baker’s, stuck his head in and shouted at the top of his lungs, “Mainly, carrots!”, shut the door, and carried along talking to me as if nothing had happened!

(laughs). Eccentric guy!

Well, no, because you see I already had done things a bit like this myself, and this idea that you will set out your lease… I mean, those people in that bakery will have been thinking about that for a very, very long time! There is no possibility that they will ever find the answer. That’s actually a very important principle. We’re so obsessed with finding answers to things that we don’t realize the questions are actually far more important. We don’t need better answers, we need better questions. This idea of putting up questions where there possibly are no answers is very important. I used to call them time bombs. There are little things in every single release, sometimes many of them. You wouldn’t notice them at first, but years later you would sometimes see where that reference was from or to. And then you go, “Oh my God, that’s what it means!” That’s what a lot of these obscure references are actually all about. You’re not meant to get them all at once, it’s meant to be something that will continually surprise you as you go back to it and peel back the layers, and layers, and layers.

I lived in a small town called Darlington in the north-east of England and its only claim to fame is that it was at one end of the very first railway in the world—the Darlington to Stockton railway—where The Rocket, which was the very first ever train, went. And it’s [Darlington’s] only claim to fame, basically. I lived there for quite some time. There was a sex shop there. This sex shop was a British sex shop, so there wasn’t anything particularly… the laws in England meant that you couldn’t sell anything hardcore in those days, but it was a sex shop anyway.

These were the days when video recorders first became possible to get in your house. Most people didn’t buy them, they rented them. You can rent them from a television shop. I had one, and it mysteriously had a button on it which allowed you to make a new soundtrack on your video recording. I have no idea why anyone would want this but it did have this. What I used to do was go rent videos from this sex shop and put my own soundtracks on them and bring them back. So there were something like 15 videotapes being circulated—maybe more—with Hafler Trio soundtracks (laughter). I will never know!

There is no way I will ever know or ever see the reaction or anything. But that’s not the point! That is the thread that runs through these people, the greats. You don’t care! It’s going to live a life completely independent of you, and you don’t know. And you don’t really care! It’s out there like a child: you prepare it the best you can, but you don’t really have any control over what’s gonna go on. That’s true of anybody who does anything in public—you can get misinterpreted, and all sorts of misapprehensions, sometimes quite serious ones. But you can’t control it; as much as you might like to, you can’t! It’s better to just build into the whole scenario this possibility. I’m sure there’s a huge possibility that someone had taken one of those videotapes and put it on and had their lives changed. That’s what it’s all about.

Later, I was getting involved into different philosophies where this idea of a shock—which completely turns your world upside down. This comes from George Gurjieff, one of my major influences. Again, that was the whole point of dadaism; dada is far more interesting than surrealism. It was quite a rough shaking that you were getting, originally. To be able to see the world from a completely new perspective even if you didn’t quite want to. So there was a sort of belligerent aspect, you could say. But not for the sake of doing that—it was actually for the sake of providing this sort of opportunity, just like with the great records, and books, and films, and stuff that had a big influence on me—they were major shocks! They weren’t just pleasant interludes, they were really foundation stones of a completely new way of seeing things: a new perspective.

Thanks for sharing that story. That’s fascinating. I love it! (laughter). Does that mean that you have all these other projects that aren’t catalogued?

Oh, yes, yes—many. Something that Chris started off with Cabaret Voltaire was picking somebody at random out of the phonebook and it was a butcher in Sheffield. I don’t know if Chris is still doing it, but for many years they sent a copy of everything they did to this butcher. Most of the Hafler Trio records got sent to him with no explanation or return address (laughter). Consistency is the key thing here! So you get one, and you think, “Oh well that’s just a mistake.” And then two, and then three, and then years go by and you keep getting sent these damn records! (uproarious laughter). So there are lots of things like that.

The thing that I appreciate about this story, and the sex shop videos, is that there is an inherent humor to all this.

Oh yeah! (laughs).

How important is humor to the art that you create? Whether it’s these projects, or the actual Hafler Trio records that people know?

It’s intrinsic! Without it you can’t understand it. Unless you actually approach it with at least a large dollop of that, you’re not going to get anywhere. Most of these things are completely ridiculous! You have a list of publications on the insert of the first LP. They look like a joke, but they’re not. They’re real!

Oh, I didn’t know! I was unsure about whether they were real or not.

They are real! They are real! I sent out a whole bunch of little booklets that actually had an extensive bibliography. I spent weeks going through, in the library, the most ridiculous research papers I could possibly find. They’re real! They’re absolutely real. One was Results of Temporary Threshold Shift in the Inner Cochlea of the Chinchilla (laughter). This person spent two years researching how to make chinchillas deaf! That’s basically what he did!

The real absurd is far more absurd than anything you can make up. The real absurdities are the things that are. All of these things that I used to get accused of, “Oh, you’re just making it up”—actually, no! All the stuff that looks real is actually fake, and all the stuff that looks fake is actually real. Right from the very beginning you’re playing with this whole thing. But it’s true, the cliché that truth is stranger than fiction. It’s true! Some of the things that happened in my life, if you were to put them in a film, people would go, “Oh, no, real life isn’t like that.” But unfortunately—or, even fortunately—this is the way things turn out.

If you just take a little peek into any aspect of life, and you look at the specialists, you’ll find some people doing some very, very strange things. It’s just beneath the surface. It’s not outlandish in any way. All of those books, with the exception of one, are completely real.

Of the different Hafler Trio records, is there one that you consider to be the funniest?

(laughs delightedly). No, there are funny bits on just about all of them. To point out… no, it would sort of destroy it actually, if I was to point out some of them, it’s better if you just go find them yourself.

I agree with that, that makes sense.

There are really obvious ones. For example, I got a title from a record I grew up with of an English comedian called Tony Hancock. There's this series of three records which were originally a wedding present for somebody: Cleave, No Man Put Asunder, and… the other one [No More Twain, Of One Flesh: 11 Unequivocal Obsecrations]. I called it a trilogy in thee parts, which is completely stupid because that’s what a trilogy is! Of course, nobody picks up on that, they just say, “Ah, a trilogy in three parts.” But it’s really stupid! (laughter).

There's the whole thing about the Irish saying, they take jokes very seriously, and everything serious as a joke. To look beyond just being absurd, it’s also one of the reasons artificial intelligence is having great problems with jokes, because jokes involve being able to see something from multiple perspectives simultaneously. That’s why they work, and that’s why computers, and computer languages—which are based on logic—can’t handle it because something is either one thing, or another thing, and can’t be two things at once. That’s why it’s sort of a resistance movement against reducing everything to this materialist view of the world.

The first record is also a critique of that scientific method. There are many levels to it. A lot of it is done screaming with laughter! This is the one thing that’s missing from all these histories of industrial music—if you want to call it that—or any of these kinds of histories that are coming out now that people are dying and everyone is deciding to write these things, is just how silly it all was. All this pall-faced, (mockingly deep serious voice) “Serious research into the dark underbelly of the subconscious.” Actually, no. For the most part, no. They’re just doing really, really daft things. But from the daft things you also get all sorts of extremely interesting things as well. All the greats, the great writers have got that memo. James Joyce for example, Beckett, The Residents. There’s always something. All the people who take themselves way too seriously, you can spot them a mile off. I know there’s a tendency to overlook that, because they think if it’s funny it can’t be serious.

Yeah, it’s a false dichotomy.

Yeah! Exactly. Just like with a novel, a great joke can contain great truth. That’s why it hits home so hard. It’s also extremely direct. You don’t have to argue with someone, or convince them of something. You either convince them of something or not. You’re not going to convince someone of something by explaining it.

I totally appreciate you saying that. I think it’s good and totally in line with the whole ethos of the Hafler Trio. It totally is this better experience when you discover it on your own, or when you stumble upon things, or when you sit with things and realize stuff later on.

I think so. Like I say, a lot of them are time bombs and they do eventually go off. I remember the very first Hafler Trio performance I ever did was in Holland. It was basically lectures. We never intended to do ordinary concerts either. It was a series of lectures in Holland. I got a letter 25 years letter saying, “Oh, I finally get it!” That’s the sort of thing that interests me, when you can make something that can resonate for that long.

The effect of that is going to be far more useful—I think—than something which just titillates, or amuses. There’s nothing wrong with amusing, or titillating, or whatever, but if you really want to allow people to have that kind of experience that I was talking about when I was first buying records—the ones where your life is actually going to change—then you have to be really clever about it now. People are so much more sophisticated and they have access to so many more things, and they have so many more explanations that they’ve already had and all the rest of it. You’ve got to be really on your toes now to be able to do it now, to seduce, or to threaten, or to shock. People have seen it all, and they’ve heard it all. It’s very hard. You have to bury the bones very, very deep.

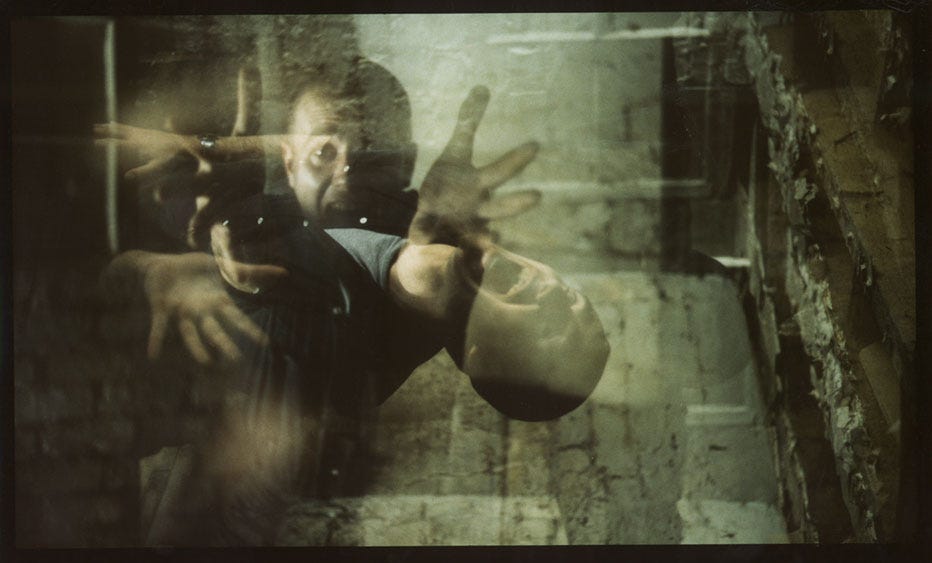

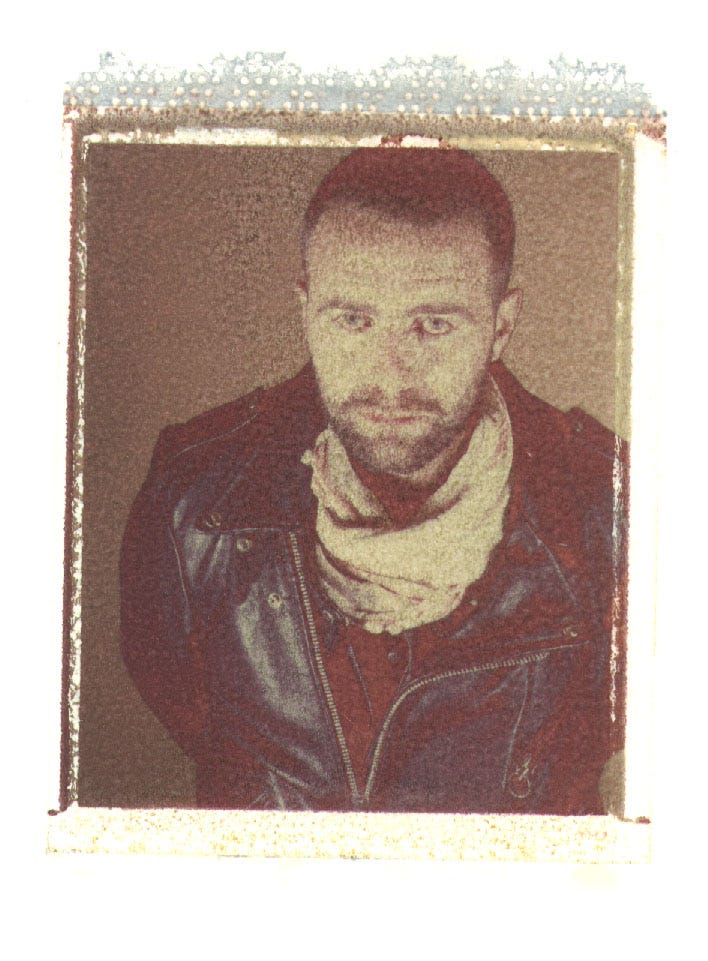

McKenzie and Willem de Ridder in Iceland

That’s a good way of putting it. To shift gears a little bit, you’ve collaborated with a large number of artists. Are there any artists—after having worked with Chris—that come to mind that you feel like really transformed the way you thought about your artistry?

It wasn’t so much that they changed anything artistic, it was just the way that they lived. I lived with Willem de Ridder for quite some years. That, of all the people I ever had anything to do with--but it wasn’t anything to do with the art, it was his basic attitude towards life.

Can you talk to me about him? Slowscan just put out a record of his works. I’m not super familiar with him aside from that one and a few other records. Can you talk to me about what it was like living with him and the way he viewed life?

Willem was the head of Fluxus in Europe in the ’60s. That mainly ended up being—in good Dutch fashion—he was basically the one who had all the merchandise (laughter). But before that he had done various things. He was doing layout design—layout design in those days was basically just cut-and-paste and drawing, there were no computers or anything like that—for a magazine called Hit Week--or Hitweek, in Dutch. It basically invented the idea of being a teenager in Holland. There was no concept of teenagers in those days. The teenager is basically a late ’50s, early ’60s invention. This was the magazine.

He would go to the place where they printed it and he would always do the layouts last thing. He would basically finish it off at the layout table at the printer and fall asleep beneath it. He eventually ended up living there, with the people who made the magazine—they took over the printer's place. That house became—in those days, that was when Americans first got cheap flights to Europe, and they would turn up, get off the plane, and they would have a piece of paper in their hand and this house would be the address they’d have. They’d turn up and that door was never closed. It was never locked. You could sleep on the floor and you could basically get involved.

About 100 meters away from this house was the Concertgebouw, which was one of the major music halls in Amsterdam. You’d have situations where The Doors played there, and The Doors played there and Jim Morrison was so stoned he couldn’t go on stage. So the three other members kept on playing and he just fell asleep at this house 100 meters away. Stuff like this used to happen all the time.

It was four floors, this house, filled with basically all the people that worked on the magazine. That house was a magnet for many, many years. Another magazine came out of it called Aloha. One of the people [Koos Zwart] involved in it made the cover of Time magazine because he used to read out the drug prices on the radio as if it was the stock exchange (laughs). It was the invention of counterculture, or youth culture, in Amsterdam. After I moved to Amsterdam and got introduced to Willem, I went around the house and they were making radio plays, and I helped them do that. I gradually ended up living there, after spending more and more time there. It was the most amazing place to be. You would wake up, you would have no idea who would be there, you would have no idea what would go on. There was always some lunatic who just arrived from somewhere who was a friend of a friend of a friend who ended up sleeping on the sofa somewhere or whatever. That was before the internet. I met a lot of people who came through that house who later became quite famous, but who were not known then.

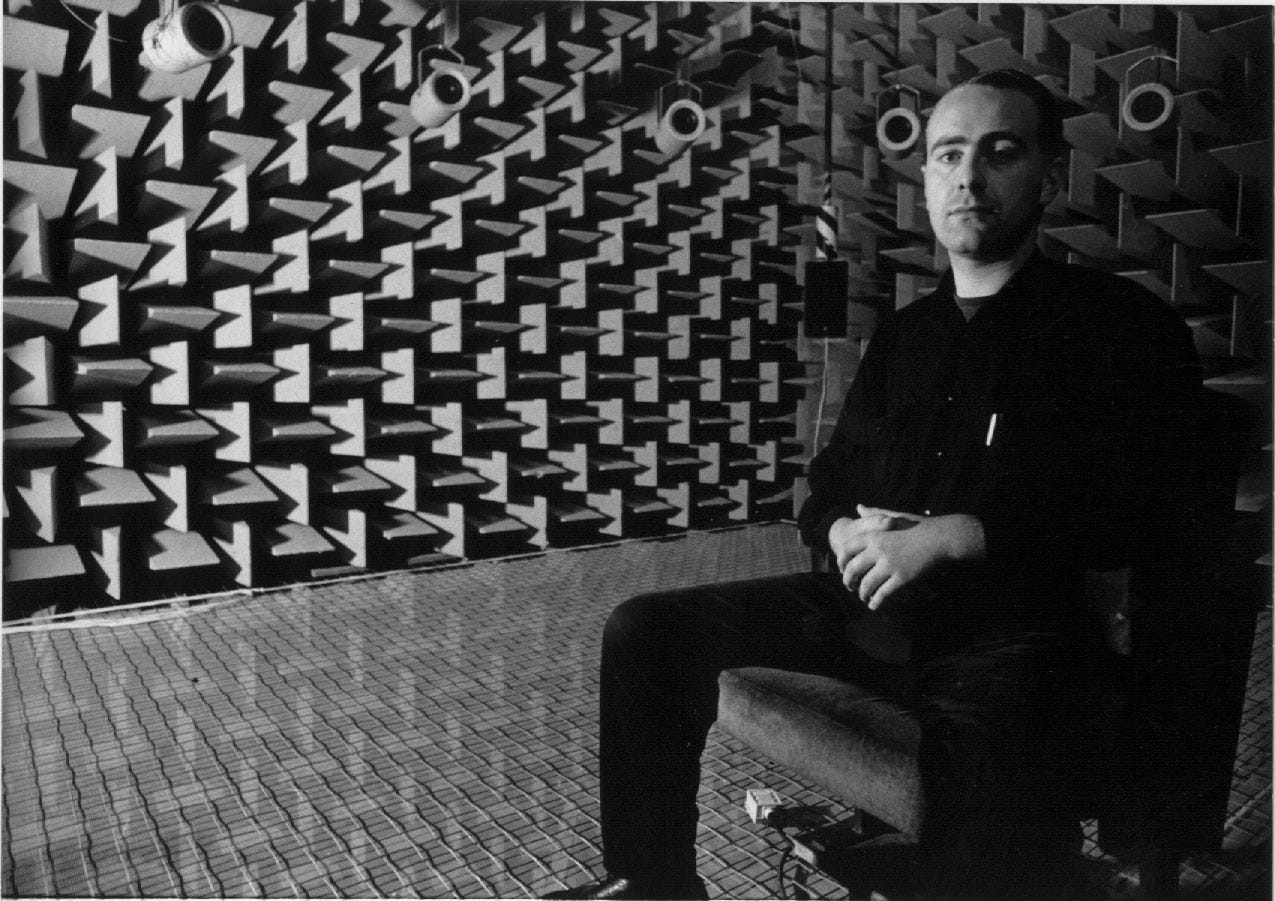

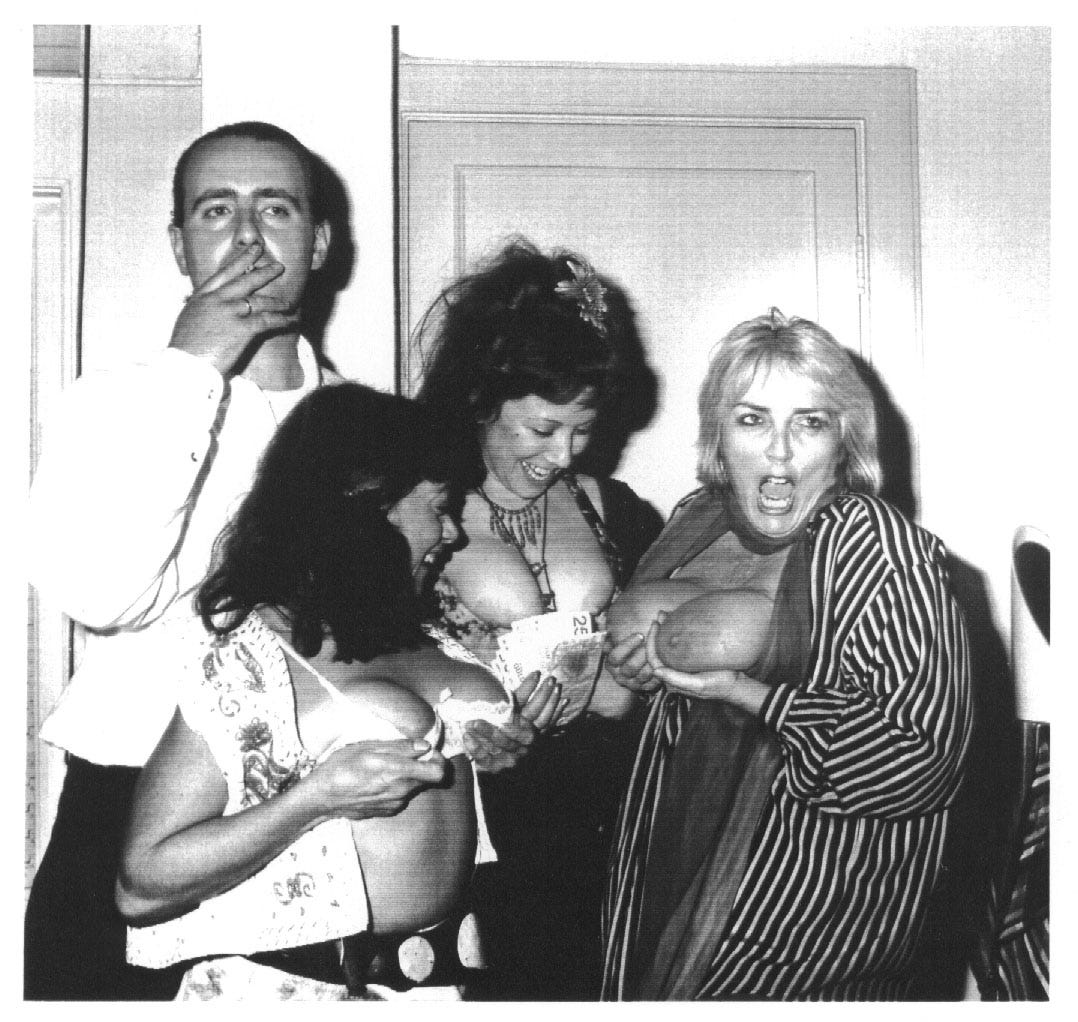

McKenzie (far left), Annie Sprinkle (second from right), Xaviera Hollander (far right)

Like who?

Like Fakir Musafar for example. He became a good friend [of Willem's] because he was a friend of Annie Sprinkle, and Annie Sprinkle had been Willem’s girlfriend in Italy years before. He came through with his bizarre French wife. But yeah, people who are now famous on the internet, and all sorts of things.

Coupled to that, the woman who basically ran the whole place, she worked as the programmer at a new age center, or the new age center, called De Kosmos in Amsterdam. These people would come along to give what we would now call new age talks, but they would come to the house to either stay, or eat, or something like that. A lot of these people, most of them were completely insane! There’s no other word for it! Incredibly stimulating. We made magazines and newspapers, radio plays—we did all sorts of stuff. We had a little bit of equipment which I was able to use. Most of my stuff has always been broken, or hasn’t worked properly, or is far too old. I’ve always just begged or borrowed stuff.

The biggest project we ever did was the Annie Sprinkle book. She came to Amsterdam to do her one woman show, which was basically her life story. She’d done it in America, but it caused all sorts of scandals. Willem directed it in Holland, and I ended up doing the soundtrack to it. There was a book that was to go with it published by a high quality art postcard company who also had an art gallery. They paid for this book. There was an Atari computer that had no harddisk, and I had to crack a program—I had to learn how computers worked—and I cracked this program that allowed us to do typesetting on it. I would basically typeset this book, and it would come out of the printer very, very slowly. Willem would rip it out of the printer and cut the pieces out and then stick them all together on the book. Basically we would do that for two months.

Fax machines had just happened, so every day there would be a six-foot length of paper hanging out of the fax machines with corrections and, “Oh god, we have to do this, this photographer won’t allow us to use his photograph, so I have to take this one out, this photograph is too much for the printer…” all this kind of stuff. That’s how I learned how to do computer stuff. That became my role for Willem, and for a lot of people. Because I’m persistent, I’ll stick to something and learn it when other people just give up. In those days, operating a computer to do that kind of work was not that easy. It wasn’t like we have now. Basically, Willem being in that environment was just absolutely amazing.

What were the years you were living with him?

I’m terrible at remembering years (laughter). Honestly, I’m really, really bad. It must have been the late ’80s. That’s all I can say really.

That would make sense.

I would have to do some weird calculations to figure it out. But then it all came to an end, and it was all very sad when it did. But then I moved to Iceland. But it was already falling to pieces. Its time had come, its time was over—I was very sad to see it go!

You mentioned earlier that weather doesn’t sit right with your body, and I know the past 30 years you’ve had an illness. I actually don’t know what illness you have—

Several! (laughs). There’s also a problem with getting things diagnosed properly because I’m not insured, and it’s always been a bit difficult to get anything properly diagnosed. What we do know for sure is that I have arthritis and gout all at the same time, extremely bad psoriasis—this is all probably linked to other [immune system and liver] things as well. I haven’t been able to walk properly for quite a long time now. This has all been going on for literally 30 years.

Given this, obviously you have to approach creating art differently to accommodate what your body is like now. Are there certain ways in which you approach art differently, or created art differently because of this?

I’m pretty tired a lot of the time, that’s also one of the problems. But no, I just carry on. That’s okay. I’m not really doing sound stuff anymore because, well, the whole thing has changed so much. I’m not really very interested in taking part of that whole thing anymore. I do this Tibetan (and other kinds of) calligraphy. I like doing that much more! (laughs).

When did you feel like you got disillusions about wanting to be a part of this whole music world?

Well, I didn’t have anything to do with it for some years because I gradually moved to Denmark—but not really, because I was living in Iceland at the same time as well. Again, this sort of, “Well, nobody else can do this so why don’t you do it?” And then I open my big fat mouth and say, “Okay, I’ll do it.” Then I stupidly got roped into doing some rather crazy computer work for police and governments and all sorts of other stuff that I can’t even talk to you about. Really hardcore stuff, we’re not talking about web design here! (laughter). At a certain point I could even program assembler—that’s one step away from zeros and ones. Pretty hardcore stuff. For three or four years, maybe even longer, I didn’t really do anything to do with this.

This is when everybody came on to the internet. This is when businesses had websites and started to get interested, and ordinary people could get access in one way or another. It just wasn’t interesting—to me it just wasn’t interesting. You have this whole rise of this first wave of people that were genuinely interested in doing something different, but then came a wave of people saying, “Me too!”, at that time. There would be people who thought, “Well, I’ve been buying this person’s records for years. Let’s start up a record label and I’ll put my own stuff out.” It just became too much. I used to use the analogy of a swimming pool. You’ve got a swimming pool, and there’s a little area where the children are supposed to be, and they pee—they don't know they’re not supposed to pee, so they pee. But the pee doesn’t stay in that corner, it just goes everywhere. It spreads out, so then everybody gets it. That’s to me what the internet did to all of this stuff.

Just like we talked about before, the value of everything just started to disappear. There’s a lot of criticism you can level with people like me—us old farts who are not with it and don’t understand this whole thing. There’s an Oscar Wilde quote where you “know the price of everything and the value of nothing.” That’s how it seems to me now. Everybody can do it now. But that doesn’t mean everybody should do it. (laughter).

There’s a great side to it, it means that it’s easier and more accessible to many, many people. But that’s also its downside. It’s like we talked about at the very beginning—how do you rate these things? How do you value one thing against another? Well, in a world where you have to constantly be seeking out the next new thing, if one thing is being a little tricky and a little difficult, you just pass on to the next thing which is a bit like it and it’s easier to access. That’s what people do.

I also did quite a lot of psychotherapy and hypnotherapy with people [I was the therapist, not the client] . I think the only changes that you can make in the same way that I had when I was first listening to records is you do one-on-one now. You don’t do it by producing an artifact, you do it by having an actual interaction with a person. That’s why I started doing workshops where I would introduce these ideas that I had collected over the years, whether I had been given them, or stole them, or seduced them out of somebody—whatever it was—and then gave them back to people. They were—and are—applicable to way more situations than just artistic things. Basically anybody could make use of many of these techniques. That’s a direct thing, because these days it’s fairly impossible to gather people together into that kind of situation. That hasn’t happened in quite some time.

That was what I finally ended up deciding: okay, we can make it. At the end of one of the workshops there is a 14-hour performance where all the participants use these ideas, but the “music” part of it is only a coat peg to hang these ideas on. It’s a practical application of those ideas, it doesn’t necessarily have to be a musical experience at all. It goes far beyond that. All the things I’ve ever really admired went far beyond their own mediums anyway. It was just a matter of progression.

I don’t think it’s possible, except with a very small amount of people, to have that sort of cataclysmic effect that it used to be possible to have. I think it still is possible to have that effect, but in other mediums. It has to be more direct, and it has to be more personal, and it has to be more skilled. I don’t think you can use brute force anymore. I think you have to be a lot more sophisticated. It’s a lot tougher. I would also say it’s probably more necessary than it’s ever been.

I would agree.

Good, because that’s a hard thing.

I feel like some of the most exciting things I stumble upon are things where it feels like it’s being created for a very small group of people, and they know it won’t attract a mainstream audience, or even a semi-mainstream audience.

Right. One of the most influential—if you want to talk about pieces of music—is this piece by Gurdjieff/De Hartmann, “Holy Affirming, Holy Denying, Holy Reconciling.” The whole of his philosophy is contained within that piece of music. It does exactly what the title says, it actually demonstrates this extremely central point of his philosophy in a piece of music—you feel that! You don’t need to know what that philosophy was, you actually feel it as a reality. It’s not an argument, it’s not a set of theories being put in; it’s a real, living piece of teaching done without words.

There are many cultures where that is actually done. In many pieces of Indian music there is a central point. Music is not supposed to be entertainment, it was supposed to be a teaching. Architecture wasn’t about expressing personality originally, it was about expressing the glory of God, if it was a church. Music was supposed to be representative of the stars and planets, “the music of the spheres”; it wasn’t meant to express your personality, which is mutable. We’re talking about eternal things that these art forms are supposed to express, where personality was basically unimportant. There was a greater purpose to it.

Of course, any kind of art that is based on personality is first of all limited as to what it can do, but it also ruins it as far as I’m concerned. You need to get out of the way. The best artists are the ones who get out of the way, and they allow the creative process to do what it’s supposed to do. The analogy is of a radio: if you buy a radio, you don’t want to hear a radio, you want to hear the program that’s coming through the radio, and the worse the radio is the worse it interferes with the signal. Right? The more a radio colors the signal, the worse a radio it is. That’s what it’s all about. That’s why there were never any pictures of us on any of the record covers. It’s not necessary! It’s not to do with me!

It’s a distraction if it were to be on there.

I think so. Many people feel like they need this, but I have enough experience to tell you that when people are freed from this, it’s a big relief as well. When you no longer have to deal with the personality of the person who created this thing, you can really benefit from this channeling that they did. You don’t own it. It’s not an ownership kind of thing. You may be very skilled at channeling, and that can be a reason why people go and see you do what you do, or listen to or read what you do. But as soon as you start to color it, that’s a big red flag, really.

I think most of the things that I’ve ever really admired have been of that nature. If I read Raymond Roussel, the French writer, he’s not there. It’s a very strange experience, there’s no author, it’s just there. It’s extremely strange stuff. You have The Residents, you didn’t even know who they were. Well, you know now obviously, but not then.

I’m very into everything you’re saying because it feels so consistent with your whole life and what you care about and the art that you’ve made.

Thanks very much, thank you!

I don’t actually have any other questions! Is there anything else that you wanted to talk about, or wanted to be asked in this interview?

Pssh, no, unless you wanted to go through that list of things, but they were already—

No, no that’s not necessary. I know that you might be against this—and that’s totally fine—but with the Jim O’Rourke interview that I did that you contacted me about initially, I had Jim list some records that he liked, that he said he feels never got their due. Is that something you’d be interested in? I understand if you’d be averse to that.

I’ll think about it. I’m not rejecting it out of hand, but it’s a bit tricky because I would have to explain why in most cases. A lot of the things that did it for me then are—a lot of people now know who Florence Foster Jenkins was. Now, I tell you, before that Hollywood film was made, very few people knew who Florence Foster Jenkins was. People of my generation will always remember where they were when they heard her for the first time (laughs). There’s no question of it!

Now, of course, it’s too knowing. There’s no innocence to it anymore. The same is true of Mrs. Miller, or these weird people who used to exist; weirdness is now just a style. It’s too self-conscious. The people who are genuinely weird were just weird. Just like Alan Cook was not weird, he was just an oddball. He wasn’t doing it for attention, it was just who he was!

You can’t make blanket statements about all of this stuff, but I could, of course, list a whole bunch of stuff, but I’d have to really explain it so much that maybe it would destroy it.

Yeah, that’s the other thing I was thinking about, because if you were to explain it, that goes against what you were saying earlier: It tells the person reading what to expect. I’m okay with whatever, but I’m also okay with you not doing it at all too. I was just throwing it out there just because you know a lot of music, you know a lot of weird music, you know a lot of music that isn’t necessarily popular.

You know, I performed that function for Iceland. When I moved to Iceland, I came over there with a whole bunch of records. Basically, everybody just borrowed all of those damn records. Stilluppsteypa, I don’t know if you ever heard of Stilluppsteypa, with Helgi [Thorsson] and Sigtryggur [Berg Sigmarsson]. Anyway, they’re sort of Nurse With Wound-ish, or they were anyways. When I came through Iceland they were a rockabilly group (laughs). Björk used to borrow a few weird records from me. I introduced a lot of people to… there’s a quote somewhere on the internet you can find from Björk who said that there was no avant-garde music in Iceland until I moved there.

Jóhann Jóhannsson, who died a few years ago… we used to share this crappy studio, I used to suggest things to him. Several of those became, well, that’s how he made his career. It’s not me, but that record collection—which disappeared—was actually hugely influential. Again, you can’t predict where these things are gonna come from. Nobody could have predicted that I would move to Iceland and lend these records to people, or that they would steal them or whatever, and that it would have such an effect.

It depends very much on the individual circumstances. Jóhann at that point had gotten some recognition for some of his stuff, but he hadn’t really made himself into his own voice. You can find interviews with him where he says hearing [these] records was totally pivotal to what he ended up doing. There’s a few records that really had this [effect]. He could never have predicted this. Nobody could have predicted this, but the effect that it had on him, I’m sure it wouldn’t have… there’s a couple records where people can’t hear them that way now. I can remember playing him Jesus Blood Never Failed Me Yet. I remember the look on his face, because that is what changed his life into making this hybrid between this very emotional music, and the slightly experimental side of things. Before that, he hadn’t done that. But hearing that record, for him, was the start of him making those kinds of records, which of course he did so very well.

I don’t want to give the impression that I’m trying to steal any thunder here, but what I’m trying to point out is that he would have never predicted that. Stilluppsteypa were a Rockabilly group, I remember playing them a Nurse With Wound record and they just looked in astonishment that this kind of thing actually existed. I’m not sure you can have that effect now. If I was to put forward a list of things that used to do that, I’m not sure that they would do that again to anybody else. I’m sure you understand what I’m saying.

Yeah that makes sense. Thank you so much for talking with me.

There’s another few hours worth in there as well if you ever wanted.

I’m sure we can talk again sometime in the future.

I’d be happy to. I remember a lot of people in my generation would say, (in a grumpy voice) “Oh, these interviews.” But they’re actually a great opportunity to find out what you think because if you’ve got to put into words something which has just been floating around in your head like grey soup—if I have to explain it to you and put into words, I get to see it more clearly. I think there’s an enormous value in that, so thank you very much.

Purchase music from The Hafler Trio at Bandcamp. Visit McKenzie’s Simply Superior website.

Thank you for reading this special midweek issue of Tone Glow. Take art seriously!