Tone Glow 032: Jean-Marie Mercimek

An interview with Jean-Marie Mercimek + album downloads and our writers panel on Sarah Davachi's 'Cantus, Descant' and Sarah Hennies's 'The Reinvention of Romance'

Jean-Marie Mercimek

Jean-Marie Mercimek is a French duo made up of Marion Molle and Ronan Riou. The two have been creating music together for the past few years, and released their debut album, Le voyage avec Jean-Marie, in 2017. They’ve recently released their follow-up, La Flourenn en Mars, and it features a fantastical mix of field recordings, electronics, and pop. Joshua Minsoo Kim talked with Jean-Marie Mercimek on September 13th, 2020 via Zoom to discuss the origins of their duo, their new album, and more.

Marion Molle and Ronan Riou

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Thank you so much for doing this, I’m excited to talk with you both. I really love the new album [La Flourenn en Mars], and I love the album you made a few years ago [Le voyage avec Jean-Marie]. To start off, can you start off by saying your name, and also when you first started getting into playing music. How old were you, what were you playing?

Marion Molle: I start? (laughs).

Yeah!

Marion Molle: Okay, so I’m Marion Molle, and I started making music when I was a child. I think I started when I was six years old—I was learning the violin. I went to a classical violin course and a music theory [course].

Ronan Riou: My name is Ronan Riou, and I started music maybe more when I was a teenager. Me and my sister started when we were kids, but it was a very bad experience. My sister was crying during the lesson, so we left together (laughter). When I was a teenager I played in a traditional band from Brittany called Bagad. So I started back with this kind of music, with folk. I also played the accordion. I also studied music for my bachelors, I studied a bit of music. Was this what I had to answer? I don’t remember the question.

No that’s good! (laughter). How did you two first meet? When did you start making music together, how did that happen?

Marion Molle: I think we met at a film festival in the deep countryside where I’m from. We had a common friend, so that’s how we met, with this friend that I came with. At the time I was living in Amsterdam becauseI was studying there. We got along really well, and we actually became a couple then afterwards.

Oh! You two are dating?

Marion Molle: We’re not anymore, but we used to!

Ah, I see.

Marion Molle: And I think—maybe you can say how we started playing music together, Ronan!

Ronan Riou: Yeah, it was in your flat, no?

Marion Molle: Yeah! I think it was for this music game we were playing, Le Marathon de la semaine.

Ronan Riou: Was it?

Marion Molle: I thought so! (laughs).

Ronan Riou: I don’t—I think it was a game with your PMC. She had a… how do you call it?

Marion Molle: A synthesizer.

Ronan Riou: Yes, she had a real synthesizer, from Holland.

Marion Molle: A real synthesizer (laughs).

Ronan Riou: You put a tape inside and we recorded on this, and then it became the beginning of the first tape.

Marion Molle: That’s true, right.

Ronan Riou: And then the rest was the cadavre exquis game with your friend.

Marion Molle: Because I think one thing that made us play more together was this online game that we both participated in. Each week you would get a theme and you had to make a song. There was a whole point [system] with how fast you made this song, and if people like it, then you got more points. This made us play and experiment a lot together.

How many people were a part of this game? Was this something that you and your friends did? Was it on a public website?

Marion Molle: Yeah, it’s on a website. It started with a few people—I wasn’t playing, but Ronan used to play for a long time I think, since almost the beginning.

Ronan Riou: About five years—the game had gone for about ten years or something. At first there were about ten people, but now it still exists!

Marion Molle: It still exists, and a lot of people are playing!

Ronan Riou: Yeah there is a big crowd, 40 or 50 people.

Marion Molle: A lot of French people (laughs), French musicians. They have a website, it’s called Le Marathon de la semaine, so it’s like The Weekly Marathon.

How do you feel that being a part of that helped you, then? Were there specific ideas or types of music that you wouldn’t have tried making if you didn’t have this game?

Marion Molle: (thinking) …You mean if this game made us experiment with different types of music?

Yeah.

Marion Molle: I guess so, yeah. It doesn’t have to be a specific style, but I think we liked to use this game to try new things, like sometimes really weird things.

Ronan Riou: It helped to increase the narrative of our music, to tell stories. I remember we adapted some dialogues or books we have on vinyl. It was a good place to do that.

I like your albums because they both have a narrative, and it always feels like you’re telling a story. Even with the new vinyl, you have the art that you made, on the front and the back cover.

Ronan Riou: The first album we made, the tape we started with, it deals also with—not random, but found stuff. We collected sounds and then we made a mixture.

Marion Molle: A collage, it’s sort of a collage. Both of these albums, they took very long to make and to finish (laughs). It’s a really long process. A lot of things from different years. We have a lot of material, and a lot of music. It’s all about putting it together and telling a story from the material we have.

Ronan Riou: And from the life we are experiencing, also. I remember on the first album I had some sounds from my trouble in Cambodia. I had some sounds of the really heavy rain, and some sounds of the tropical forests in Thailand. It also tells some little stories from our lives, and the fairy tales that we can bring around.

Marion Molle: Some parts are things that we composed, composition work. There is also a lot of jamming and improvisations and field recordings.

What was the hardest part about making these albums for you?

Marion Molle: (laughs). Difficult question! I think the hardest thing was that it took so long (laughs). For me, it’s that it still would make sense after all these things. The album was finished two years ago. Making the cover, it took a long time to agree on what we wanted. It was a lot of work!

Ronan Riou: I think that was where we had the most problems.

Marion Molle: It’s true! (laughter). I guess that was the problem, yeah. We thought about asking some other artist we like, but we are used to controlling everything and doing everything ourselves. We both like to draw also, so we wanted to do it. But being so far apart…

Ronan Riou: We spent so many months trying to make some graphic designs, but we didn’t like what we did. We were fighting every time. When we were in Paris together for a few hours we made the cover—we had to meet for it.

Was the music something you two made together in person?

Marion Molle: Yeah, it became difficult when we moved apart. When I started to have this full time job it was difficult to work from a distance. Before, all the music was made while we were living together.

Ronan Riou: On the new album, some parts of the music is just you alone playing.

Marion Molle: That’s different from the first album. Some parts are composed only by me.

Ronan Riou: And mixed with my text.

Ronan Riou and Marion Molle

You worked together on this album. Can you share what you feel the other person brings to this project? What does the other person do that you can’t that makes this project better?

Ronan Riou: First, it is about having a vibe that you cannot extract from your own habits. Marion can work really efficiently, she said earlier that she found it took too much time to do everything, but she likes to go fast. For me, I’m really slow in getting an idea. I have some projects that can last forever, for years. It’s something that has to come alive in me. But I also like what Marion brings, to… (explosion noises and hand gestures), to spit it up. (laughter). The music that she builds, the funny sounds… it’s hard for me to explain (laughter).

Marion Molle: What I like about Ronan is his ability to listen. It’s also hard to explain. I think he has a very sensitive ear, and he can… it’s hard to say! (laughs). He can make something balanced, but he knows how to balance not only sounds, but also energy, how to get to what comes next. All these collage things, I really like how he approaches that. I like how he knows how to collect. Sometimes I am so into what I do it’s almost like I can’t hear it, but I have the feeling that Ronan is good at stepping back and saying, “Well, that’s what sounds wrong, and we should do that, and that.” These little details are what make it balanced.

Thanks so much for sharing, I really like that. I love how your music has this fairy tale aspect. Were you thinking of any specific fairy tales, or any stories in general when you were making this new album?

Ronan Riou: Actually, the text that Marion was reading in French were largely extracted from Jean Giono, a French writer from the southeast, from Manosque. From the Provence. I really love how he can describe nature and bring myths alive through nature. I really loved it so I took some sentences from one book I have, and I put the sentences in a different order, so it’s a kind of like poetry from his words.

Also from another book I have, a French painter from nearby Brittany named Lucien Pouëdras. His paintings are from life in the countryside some time ago. You can see in his paintings scenes of people working in the fields and in the village, so it’s close by. It can also join with the ideas of Jean Giono, who is really talking a lot about his life on the coast.

Marion Molle: Also there is one last part from Gargantua by this Renaissance writer François Rabelais, who was a writer from the Renaissance.

I know Jean Giono because he’s the one who wrote The Man Who Planted Trees.

Ronan Riou: Yes!

What book were you taking the text from, for this album?

Ronan Riou: It was Le chant du monde.

It’s okay!

Ronan Riou: I have a book now, it’s called Rondeur des Jours, or The Roundness of Days. All the names of his books are already dreamy and blend together, so I don’t remember the name. I think it was from your mother, Marion!

Marion Molle: Oh yeah! (laughs). I don’t remember either.

It’s interesting how you are influenced by artists who aren’t musicians. For the album, were you looking at other types of music at all though? Or were you just thinking about Jean Giono and the painter, trying to capture that feeling?

Marion Molle: I don’t think we were influenced by the text for the music. It’s more about, at least for me, I always have a hard time writing, and I like when there is text or when there is voice in music. It was more so something to help with finding words, but it’s not that we started with this to make the music. Being influenced by musicians… I guess we are, but we were not thinking consciously about specific musicians. I don’t remember thinking about a specific music, what about you Ronan?

Ronan Riou: I was thinking also that Jean Giono came along when I was starting to build this vinyl collage at your grandfather’s house. That was when I started to collect all the music we recorded. I was with this book by Jean Giono when we were doing this. It was not when we were making the music, though. We were just playing music like we did all the time in France.

Marion Molle: In between these two albums we made a lot of live sets. We were asked to play live, and for that we had to figure out different ways to make music. All these sets—we had many—we never recorded. Some of the music on the album is maybe from… I think there was one residency we did where we were jamming a lot, and then from these jams we—

Ronan Riou: These jams weren’t played live, though.

Marion Molle: Yeah, so we selected them for the album. It was a lot of things coming from different moments.

Did you have a specific goal for the album? Is there something that you wanted listeners to get out of it, to feel or to understand?

Marion Molle: I think one goal was to not make the same album that we made before. (laughs). We didn’t want to repeat ourselves. With sound collage it can easily become that.

Ronan Riou: A goal was maybe to increase the fairy tale aspect with this long track you made, Marion.

Marion Molle: Yeah.

Ronan Riou: Like you said, we wanted to change from our first album, which had shorter sounds.

Marion Molle: We tried to have longer [sounds], but otherwise it was more like trying to make something that you would like to find yourself. Something that we would like to stumble upon.

Can you share your favorite fairy tale? Do you have a favorite fairy tale?

Marion Molle: I don’t! I have a very bad memory for names and everything. I’m sure there are fairy tales I love, but I can’t tell you one right now!

Ronan Riou: It’s hard for me to have a favorite thing, like a favorite music, or a favorite movie.

Marion Molle: Yes, it is the same for me (laughs).

Ronan Riou: When you ask this I first think of Passolini, he made a movie that I really like, Canterbury Tales. I don’t know, I don’t have a favorite fairy tale.

A painting by Ronan Riou for an expo in Antwerp

When you make music do you have specific images that help guide what you make? I’m wondering if you think very visually when you work with any sort of art, if that visual aspect is something you think about.

Ronan Riou: I think all the time that I have these—not primitive, but rough aspects. So when I’m creating maybe I see some mud or stuff like this (laughter). It’s just an example! I think we have to create a vibe. I also like to paint, so it’s really connected to colors and shapes and sounds. Also text, I really like to switch from text or poetry.

Marion Molle: I remember after we made the first album we were asked to play some live concerts. The first thing we did was make film. At first we were so lost in what we would do on the scene. We first made a film, and for the concert we played the film and we played a soundtrack to the film. So we were making a soundtrack for a film. We made the film in the same way that we made the music: we just used images we had, as we would just use sounds that we had. It’s a very weird collage. This you can see on YouTube, I uploaded it.

Ronan Riou: The first show was really connected to the first tape. It was trying to do that as found footage.

I just want to say I really like the name of your project. Someone just told me how it’s supposed to be like, “Thanks dude” in French—merci mec! (laughter).

Ronan Riou: Actually, it’s the name of a soup—

Marion Molle: It sounds like that in French, but Mercimek—the way we wrote it—is a Turkish word for red lentil soup. (laughter).

I love it! Wow! So you just like the soup a lot? Is that why you came up with the name?

Ronan Riou: I like the soup! (laughter). It’s like I said about favorites, I like this soup, but I don’t have a favorite meal (laughter). Actually the name—we have to tell the story of the kombucha!

Marion Molle: We had these friends that gave us this kombucha, and they said to us, “You should give it a name and take care of it.” Jean-Marie Mercimek was the name of our kombucha (laughter). So that’s actually how we got the name.

That’s funny, that’s cute (laughter). What is the French underground music scene like right now? I think a lot of people in America don’t know anything that’s going on. Can you describe what it’s like, what the musicians are like, what the shows are like. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Marion Molle: You can go first, Ronan. (laughs).

Ronan Riou: I’m trying to find my words. There are a lot of little places who welcome concerts, or in some bars…

Marion Molle: There is a big underground, kind of. Quite big I think. A lot of people organizing. Once you step in there, it’s easy to tour around France. There are a lot of very nice people organizing and welcoming you. I think it’s hard to say because that’s one thing, the experimental scene is big, the underground scene is big (which we know, because we have a lot of friends involved in it). I think it depends on which city you are in. For example in Marseille it’s a lot about trap music and rap. In Brittany, there are a lot of musicians there as well. A lot of people are organizing.

Ronan Riou: There are a lot of little festivals. This summer in Brittany there were so many, even with this COVID vibe. There is a lot happening, just a lot of D.I.Y. scenes. It’s also connected with this—not eye-level, but more in the big… um…

Marion Molle: Professional?

Ronan Riou: Yes, in the professional world. I know in Brussels, in Belgium, we have some friends that come from the D.I.Y. scene, and now they are playing and making music for movies and theater, plays. The dance scene is really connected also, there is a lot of experimental dance.

Marion Molle: Yeah, I think we know more… at least I feel I have more friends who are into music who live in Belgium, Brussels or Brittany. For example, now I live in Paris, and I actually don’t know that many musicians here. And I’m sure there is a scene here. I had the feeling Paris was more active.

Marion Molle photographed by Ronan Riou (seen in the reflection)

Are there any underground French artists that you two want to shout out so people reading can check out their music too? (laughter). You can even shout out your friends, it doesn’t matter!

Marion Molle: Yeah, you can check out my boyfriend, my new boyfriend’s music Leo Hoffsaes (laughs). He released twovery good albums recently. Otherwise, we have these two friends with a project called La Fureur De Vouivre, who released a tape recently also, which is very good.

Ronan Riou: I don’t have names… In Antwerp there’s a very good musician named Fyoelk, he’s making electronic music, dance, almost Italo disco. Also, there are people like Francesco Cavaliere from Italy. In France there’s also Humbros and Au revoir la société étrange.

I don’t have any other questions. Is there anything else that you two wanted to mention or talk about, anything that you wanted to make sure you say? (silence). It’s okay if you don’t!

Marion Molle: (laughs).

Ronan Riou: I was thinking also to say that Jean-Marie is a character who died recently. The name, we took it from this guy in the deep countryside in France, Jean-Marie Massou. He was a really wild guy. He was taking rocks from the mountains and recording music and making collages with radio and stuff. We learned that he just died last month, or recently. He was like 70-something. There is a movie actually, a documentary on him called Le plein pays by Antoine Boutet. It’s a good documentary!

Purchase La Flourenn en Mars at Bandcamp.

Download Corner

Every issue, Tone Glow provides download links to older, obscure albums that we believe deserve highlighting. Each download will be accompanied by a brief description of the album. Artists and labels can contact Tone Glow if you would like to see download links removed.

Takahashi Kûzan - The Sound of Bamboo (self-released, Year Unknown)

Rare is the instrument that is as simple as the shakuhachi, and rarer still that such a simple instrument has such a complex history. Essentially just a piece of bamboo cut to the right size, with a notch to blow into and five small holes to control the pitch, the very simplicity of it was what enticed the monks of the Fuke-shû sect of Zen Buddhism to start their practice of “blowing meditation” called Suizen. The concept was to use the precise breathing techniques required to play the shakuhachi as a tool for meditation and enlightenment; since carving a flute from bamboo was so easy, theoretically anyone could emulate the technique.

The Fuke-shû sect was originally an unofficial and unorganized group of Zen radicals until around the turn of the 18th century when they cohered into an organized church and appealed to the shogunate for state recognition. In return for this recognition, the shogun demanded two things: liturgical proof of their existence as an independent sect and proof of their total allegiance to the shogunate. As proof of their independence the Fuke-shû wrote the Honkyoku, a repertoire of songs for the shakuhachi in their distinctive style; as proof of their allegiance to the shogun they offered to become his spies. For the next 150 years, distinctively dressed Komusō monks roamed the islands, playing the shakuhachi and spying on the populace.

Knowledge of the Honkyoku repertoire was a calling card for shogunate agents to recognize each other in public and as such was a closely guarded secret. As the shogunate disbanded, so too did the Fuke-shû sect and the shakuhachi swiftly became a common secular instrument rather than a symbol of the religious elite. Much of what we in the West would recognize as “stereotypical shakuhachi music” from samurai movies and the like is derived from this style. That such a simple instrument could have such a complicated history is probably some sort of metaphor about the ingenuity of mankind.

Takahashi Kûzan, regarded as “the last komusō,” was born a few decades after the official disbandment of the Fuke-shû and was key to its survival into the modern era. A grandmaster in Yagyû Shin-Kage-ryû Budo by the age of 20, he thereafter devoted himself to Buddhism, going on a pilgrimage to visit the last of the living Fuke-shû grandmasters in turn and learn the Honkyoku from them. He eventually became a grandmaster of the Fuke-shû school himself, modernized and systematized the Honkyoku canon, wrote the definitive book on the history and theory of Fuke-shû shakuhachi, and travelled the world showcasing Japanese culture. The Sound of Bamboo (竹の響き) was the only album he recorded in his lifetime and is a definitive example of the Fuke-shû style. Built entirely around the beautifully expressive tone & timbre of the shakuhachi, simple pentatonic melodies become backgrounds for subtle modulations of breath, pitch, and volume, all tightly controlled and palpably focused on creating mood and feeling from the simplest of means. Sparse and gorgeous to a degree that defies the ludicrous string of historical circumstances that birthed it. —Samuel McLemore

Aum Shinrikyo - Various Recordings (not an official release)

The death penalty in Japan as we know it was established in 1993 after a series of high-profile, gruesome murders that captivated and terrified the Japanese population. By this time, an anti-cult lawyer named Tsutsumi Sakamoto had been murdered by mysterious forces after his lawsuit against the cult Aum Shinrikyo was to go forward despite their intention to negotiate. A couple years later, after the notorious sarin gas attack that decimated the Tokyo subways, it was found that Sakamoto had been killed by the same group who orchestrated the terrorism: Aum. Fast forward to 2018, and the largest group execution of all time was conducted on thirteen Aum Shinrikyo members, including their messiah figure leader Shoko Asahara. This was effectively the end of the cult, now known as Aleph.

Relitigating the cult of Aum Shinrikyo in 2020 is weirdly prescient, especially considering the rise of QAnon in the States and abroad. There is a staggering amount of magical thinking afoot that conveniently falls in line with the rise of fascism in many a country, buoyed by orthodox understanding of religion that is used for promoting hate. This is essentially how Aum operated, as Asahara became this mythical messianic whose appearances on TV and magazines led him to amass enough followers to build a substantial community, in which there was a massive compound composed of various military equipment like explosives, chemical weapons, and even a Russian military helicopter.

There was also culture. Behind the veil of terror lay a musical movement, though not much is known about to what ends the songs performed were used for. To my knowledge, when the Aum Shinrikyo compound was raided, these recordings were found and released to the public, although the only English-language archival of this is from a /mu/ sharethread, so take it with a grain of salt. The same user then shared a download link for the Jim Jones and People’s Temple Choir album, proving their cult music expertise. In any case, even with the anonymity of the posts, it’s likely these are real. There’s a certifiable creepiness throughout the compilation, like you can detect everyone playing was brainwashed by doomsday prophecies.

Notoriously, Asahara’s music was documented in The Sounds of Japanese Doomsday Cults, although it’s merely two songs. Here, he takes a backseat, though there are times when you can tell it’s his voice, like on “Keppaku”, aka “Lord Death’s Counting Song.” It’s remarkably weird new age music, reminiscent of stuff in ’80s children’s anime except pledging allegiance to a maniacal cult leader. “Habatake” is the most prominent example, the chorus a chant of “Fight! Fight! Asahara!” Pretty chilling stuff that sounds like it should be a fight song for a Koshien high school, not a Jesus figure who excitedly welcomed the rapture.

As a piece of history this makeshift compilation is endlessly fascinating. It’s a portrait of a shadowy group that operated with extreme prejudice, carrying out planned killings and tried to bend the entirety of Japan to their will. The innocence exuded by this bizarre folk music is a wild irony. You truly couldn’t ask for a more on-brand documentation of what Aum Shinrikyo was than this enigmatic collection, a calcification of theological terrorism that mirrors our current society depressingly well. —Eli Schoop

Download link: MP3

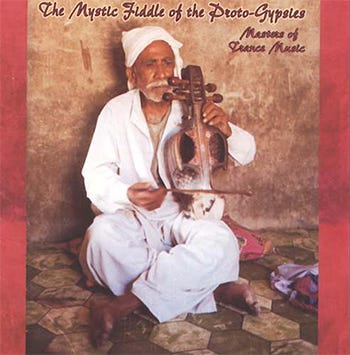

Mohammad Ramazân & Yâr Mohammad de Malir - The Mystic Fiddle Of The Proto-Gypsies: Masters Of Trance Music (Shanachie, 1997)

I don’t know who exactly is responsible for the incoherent and downright offensive title this collection of recordings was sullied with, but, considering the slew of other contemporary releases by label Shanachie with ridiculous, confusing, or racist titles, I assume the craven manner in which they attempted to pander to orientalist & colonialist urges was just their standard marketing gimmick at the time. “Mystic Trance Music” is a shallow and flashy reading of a rich and powerful tradition, the players are Baloch, not proto-anything, and even in 1997 the word “gypsy” was a slur!

Despite all this, Masters of Trance Music stands as one of the best of the rare documents of traditional Balochistani music that have been released to this day. Recorded in Pakistan in 1996 and culled from what appears to be hours of recordings of two master performers of Qalandari music designed for spiritual ceremonies called guâti-damâli, the album aptly displays the unique nature of Balochi music. Centuries of migration and the vagaries of politics have scattered the Balochi people over thousands of miles of territory and at least a half a dozen countries and their music reflects this history.

The tanburag—a three-stringed lute related to the Persian dotar—provides a sharp, chiming rhythm which never once falters or slackens while the sorud—a ten-to-thirty-stringed fiddle related to the Indian sarangi—plays melodies derived from Baloch Zahirig modes; often these are simple three or four note motifs that are effortlessly repeated and developed ad nauseum for minutes at a time until, “all of a sudden,” they are playing practically a different melody entirely. This tight, repetitive interplay between the players combined with the subtle morphing of each composition creates an astonishing flow of energy that is hard to compare to anything else in devotional or traditional music. —Samuel McLemore

Writers Panel

Every issue, Tone Glow has a panel of writers share brief thoughts on an album and assign it a score between 0 and 10. This section of the website is inspired by The Singles Jukebox.

Sarah Davachi - Cantus, Descant (Late Music, 2020)

Press Release info: The title of the record—‘Cantus, Descant’—has both literal and metaphorical meaning and, in a way, this is something like a concept album that addresses the relationship between the two. In medieval music, the Latin ‘cantus’ was used as a general term for unadorned singing or chant and by the end of the Middle Ages it came to represent the highest voice of a polyphonic choral texture, often improvised.

‘Descant’, at that time, was used in part to denote the structures of polyphony and counterpoint, the harmonious play of two or more voices against one another. Harmony is a musical device that is particularly meaningful to the material on this album, especially in the ‘Stations I-V’ series and its use of a sixteenth-century meantone temperament, but the inherent dialogue that persists between the individual (the cantus) and the larger time and space that it occupies (the descant) came to inhabit a more significant presence in the ideas and feelings that inform the album as well. In this way, the album takes solace in a suspension of the private within the collective, and the moment within the mythic.

Purchase Cantus, Descant at Bandcamp.

Nick Zanca: Sarah Davachi is at home in anachronism—whether she paints with electromechanical keyboard samplers or borrowed baroque gestures, her palettes largely remain primordial and unscathed. In an era where selfsame drone has been done to death, it’s no small feat that she consistently creates panoramas of euphony that can enjoy interchangeable functions between floral wallpaper and focal points on behalf of the listener. Her LP for Sean McCann’s Recital Program has been an early morning staple on my turntable since its release; regardless of whether I spend the crack of dawn reading in bed or nursing nasty hangovers, its textural beds are an ideal score for confronting corporeality and mindful maintenance.

I first pressed play on this double album the other morning at 7AM shortly after getting out of bed and sluggishly making my way to a horizontal position on the couch; though it became clear a few tracks in that it contributes no new developments to her oeuvre beyond introducing her curiously Kranky-ready, rotary-processed voice on two tracks, it was hardly surprising that the music worked wonders in recline. This record does it for me due to its tactile engineering—the sylvan creak of pumps and stops carry as much weight and potential for immersion as the pipes and bellows.

Considering the upgrade in distribution through partnering with Warp, perhaps the seamless sequencing here is simply meant to serve as a summation of the ground Davachi has covered so far. If that’s the case, Cantus, Descant certainly does its job. I predict some members of our panel will claim this as the work of a single-skilled specialist amid the recent tired bombardment of organ worship bred by Boomkat, but if there’s one thing I’ve learned from home listening, it’s that those typecast as musically monogamous can often contain multitudes.

[7]

Marshall Gu: In 2019, Kali Malone introduced me to a sound I didn’t know I wanted: 71 minutes of spiritually-cleansing pipe organ ambient music. This year, Sarah Davachi ups the ante: 81 minutes of ambient music played on pipe organs all over the world. I should say that the similarities end there: the songs on Kali Malone’s The Sacrificial Code were unhurried, with most songs over 10 minutes in length. By contrast, Davachi’s are roughly the same tempo but are ‘brisking by’ at five minutes. Furthermore, Davachi’s use of the pipe organ is earthier, and I don’t say that just because the cover depicts her and a lot of greenery; “Oldgrowth” features wind and the clacking of what sounds like rocks deep in the background while the pipe organ by itself evokes nature elsewhere. It’s also more varied: a bowed string floats in the air with the pipe organ on “Ruminant,” while Sarah Davachi’s own vocals grace “Play the Ghost” and “Canyon Walls”; the slow chords and echo filter accentuating the sadness in Davachi’s voice. And my personal favourite: “The Pelican,” which opens with a very Bach-sounding passage and becomes an Erik Satie nocturne performed by De Leeuw. Ultimately, both of these albums are exercises in pure minimalism and tone beauty.

[7]

Vanessa Ague: With Cantus, Descant, composer and performer Sarah Davachi makes music that shimmers with poignant resonance. An 80-minute experimentation of voice, organ, synthesizer, and piano, the album flows through a series of compelling drones that vibrate with full-bodied reverberance. At its best, it mesmerizes; at its worst, it fades away into the background, unnoticed. The sublime trembles of the bass in “Midlands,” the brilliant energy and soft voice of “Play the Ghost,” and the twinkling stillness of “Gold Upon White” stand out as the peaks of the record. In other moments, like “Canyon Walls,” the nasal-toned drone and lagging pace is a slog. Each piece exhibits a moving exploration of harmony, and a deft understanding of drone music, but at a certain point, they tend to get lost within each other. This is an album that’s best as a companion for solace and quietude, for contemplative nights and deep listening. Every moment doesn’t shine perfectly, but the sound is stunning in its tranquility, allowing you to listen and drift away.

[7]

Shy Thompson: This past week has been one of the worst I can remember. I’ve had about six straight days of physical anxiety symptoms, which mostly manifests in the form of having a sharp feeling in my chest that prevents me from doing much of anything but lying down completely motionless. Doing nothing is pretty unhelpful for anxiety, as you can imagine, so I’ve been trying my best to accomplish as many small tasks as I possibly can—those little things that I’ve been meaning to do, but I can get them done in no time so I decide to do them later. Those little things have piled up into a mountain of a to-do list, which turns out to be pretty fortunate; I have ample escape from pesky idle thoughts. I frequently pair these menial tasks with listening to music, and it’s become an effective way to get things done while being paralyzed in the face of loftier responsibilities. I decided to apply a skin to my phone while listening to Sarah Davachi’s Cantus, Descant for the first time.

It’s very cavernous, spacious music and I immediately sensed that it was not a good fit for the task that I selected. Perhaps more appropriate for prayer at a Sunday Mass with its billowing organ arrangements, I found myself spacing out and getting lost in thought while trying to follow along with a tutorial video showing how to apply the protective case. I messed up at every single step where I had to hit the adhesive with a hair dryer, and by the time the album was over it was obvious I would have to peel the thing off and try again. Cantus, Descant may not have helped me to make my Pixel 3a look cute, but it did provide me a moment where I was completely comfortable in my own mind—I’ve had precious few of those lately, so I’m appreciative.

[6]

Alex Mayle: Cantus, Descant feels like an album too afraid to say or do anything meaningful, instead content to sit around and be aesthetically pleasing. It doesn’t explore any interesting space that a drone album should, nor does it do anything particularly noteworthy with its occasional vocal interludes. I feel like it would be an insult to Sarah Davachi for me to try and diagnose where she “went wrong” here; I have no doubts that she created exactly what she wanted, and there are plenty of people who enjoy this sort of neoclassical pop drone. I’ve warmed up to a few albums in this category, though the vast majority of offerings is exceedingly bland, factory-produced slop.

I wouldn’t go so far to claim Cantus, Descant is that bad, but there’s very little on the album that makes any sort of lasting mark. The instrumental drone pieces, like the series of “Stations” tracks, aimlessly slide around exploring vaguely interesting textures while offering up nothing of value beyond that. The aesthetics don’t feel particularly entwined with anything else and I simply don’t feel anything emotional when listening to any piece. I’ve genuinely struggled to find anything positive to say about Cantus, Descant, even though it’s an alright listen. The instrumentation is pretty standard, the overrall texture of the album is fine, and there is not a single sound on the album that I can identify as bad. But there’s also nothing that I would identify as good. With how much music is out there, being inoffensive is far from the worst thing I guess. Not enough to warrant any future listens though.

[5]

Sunik Kim: Music like this brings nothing, absolutely nothing, to mind. But is that such a bad thing? There’s a certain twisted comfort (and void) to be found in blandness—not the expertly-crafted, intentional, adjective-ized (e.g. meditative, sad, thought-provoking, relaxing, scientific, materialist...) surface-level ‘blandness’ of great ‘ambient,’ ‘field recording,’ or generally ‘experimental’ music, but true blandness: I’m thinking of muzak, elevator music, lobby music, actual musical wallpaper—music that is formally conventional, not ‘ambient’ or ‘experimental,’ that definitely exists (versus being ‘studies in silence’ or ‘deep listening’ etc.), but even in its popularly recognizable existence generally provokes no reaction or thought whatsoever—the painfully visible somehow made invisible.

What is the effect of 80 minutes of such careful blandness? If anything, it’s an unexpected novelty: here, music voiced in somber, searching, emotive textures and chords (what else can the church organ be used for these days?) becomes almost entirely denatured, reduced to pure movements in sound that are tangible, instantly recognizable, but not moving in any way. The odd ‘skill’ involved in making a more-or-less bulletproof formula a void is kind of fascinating in itself—I’m imagining the kind of (truly interesting!) musical acrobatics it would take to turn a song as stunning and devastating as Judee Sill’s “The Kiss” into muzak, a mere karaoke back-up choice. At this point, I think it’s obvious that there’s only one possible score to give here.

[5]

Gil Sansón: Lovers of the organ will find much to enjoy here: its peculiar tunings, the droning of the instrument, the emphasis on air through pipes—it’s all in generous display. This is not ambient music: the music sounds big, and when it’s not, it errs towards the traditional music found in folk traditions that employ drone (it’s closer to, say, Popol Vuh than Tangerine Dream). The pieces tend to take one mode and stay in it, which may make some pieces overstay their welcome, but there’s enough variety to sustain the interest of a concentrated listening. On first hearing, a number of tracks captured my attention fully, strong in character and sound, while others went by without me registering much, as with the shorter tracks that feel more like vignettes than anything fully developed.

Cantus, Descant is often a bit too blissful for my liking, but in short doses I find it quite charming. A couple of songs with vocals and sparse guitar add a nice touch to the album, with “Canyon Walls” being a strong highlight, bringing to mind a sleepy Vashti Bunyan as well as the obvious comparison to Grouper. The album could have been fifteen minutes shorter, as the timbres do get excessive over time and most of the tracks feel like Davachi recorded a number of improvisations and selected the ones that sounded more promising; it would have been nice for a couple of tracks to include some disrupting element added for contrast.

[6]

Ryo Miyauchi: Though “Play the Ghost” and “Canyon Walls” are both what I’d more or less imagined as a Sarah Davachi vocal track, they are welcome pieces to encounter amid the organ drones. The gossamer filter that outlines the vocals gives her voice a spectral quality, like a phantasmagoric presence that hovers over an earthly organ hymn; it might evoke Liz Harris’s recent Grouper tracks but less ghastly. That said, both ultimately stick out in Cantus, Descant as an outlier than a breaking of new ground. While those two tracks provide a soothing weightlessness, Davachi’s album offers transcendence more from the immensity of the various organs. The physicality of the instrument is very much felt with each buzzing hum, and the “Station” series in particular grants me a relieving moment of decompression as I surrender to the dense reverberation.

[7]

Average: [6.25]

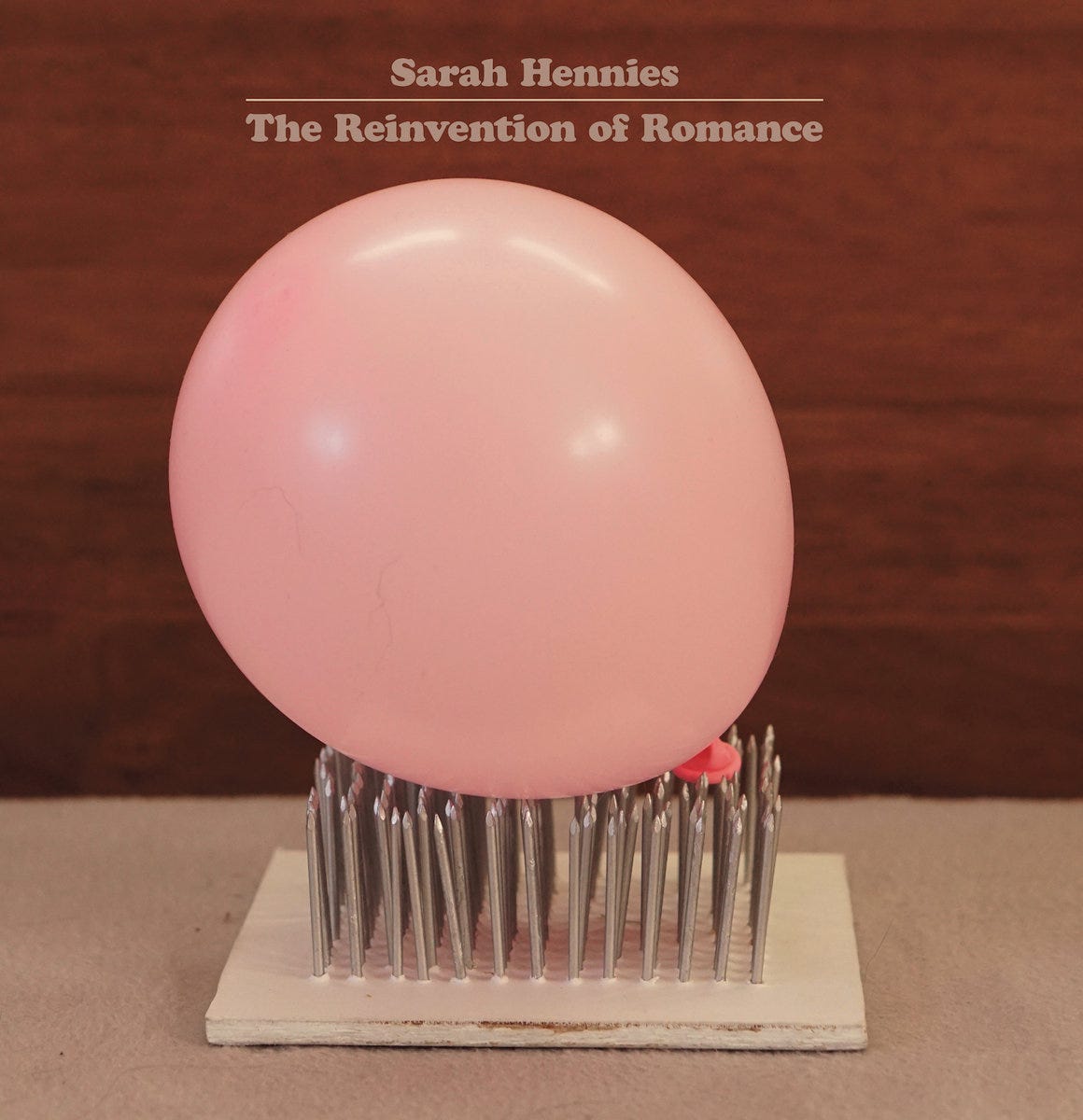

Sarah Hennies - The Reinvention of Romance (Astral Spirits, 2020)

Press Release info: The Reinvention of Romance, a new work for percussion and cello that examines the care and empathy that emerge when two lives share space. Over the course of 90 minutes, a series of repeating patterns creates a peculiar kind of harmony in which two musicians are rarely “playing together” but are nonetheless intimately bonded. The Knoxville-based duo Two-Way Street (Ashlee Booth and Adam Lion) commissioned Hennies to compose “a very long piece;” for this recording they step into its two intertwining roles.

Purchase The Reinvention of Romance at Bandcamp.

Mark Cutler: Over the last few years, Hennies has been a rising star in the world of experimental composition. After a string of pieces mostly ranging between twenty and thirty minutes in length, with many being released only online, one felt that it was high time for her to produce a Major Statement album. This 90-minute behemoth is precisely such an album.

The Reinvention of Romance, like most of Hennies’s work, is unbelievably patient. The pace varies between movements, but once a movement begins, it just pummels away at you for ten, twenty minutes. Yet this is not to say the work as a whole is monotonous. Though Adam Lion is credited simply with “percussion,” he gets to play in an extreme range of frequencies here, often sustaining ear-shredding drones on what might be a singing bowl. Likewise, Ashlee Booth sometimes plays her cello so slowly that it resembles a barely-played panpipe, or so low that it calls to mind a heavy chair dragged along a concrete floor. In this way, the piece feels remarkably full for a 90-minute duet piece in which each of the players takes extended turns playing unaccompanied.

Comparisons to later Feldman are warranted here, particularly in the earlier movements where the cello and percussion weave almost imperceptibly in and out of sync. (Notably, Hennies has performed and released a rendition of Crippled Symmetry before.) However, as the piece progresses and the two instrumentalists stray further apart, the piece becomes more unmistakably Hennies. As a reward to the patient listener, Reinvention culminates in a surprising and lovely melody. After so much time playing sonically apart—or at least at a distance—Lion and Booth converge in a torrent of sound which, after seventy acerbic minutes, feels almost overwhelming.

Reinvention is almost self-consciously punishing, both in terms of endurance and in what, specifically, one endures. It’s not a work I see myself revisiting often. However, it is a formidable achievement which will surely satisfy her existing admirers, and earn her many new ones.

[7]

Nick Zanca: Mere minutes after sitting with this piece for the first time and tenderly basking in the subsequent silence alone after sunset, my partner arrived home from catching up with an old friend after work that he hadn’t seen since the pandemic began. Inebriated, he reached for the aux cord to blast Lil Uzi Vert before stumbling to the shower. It was a beautiful and hilarious instance of anti-mimesis—the pulses and timbres of this particular day spent on our own could not have contrasted more; the space we share and curl up in together at night only accentuated the split. I’ll keep this blurb brief so as to let these sounds sing for themselves: there’s already an abundance of recorded evidence of Hennies’s non-verbal mastery of conveying the carnal and the intimate from the past few years alone, but this duet for cello and percussion (an orchestration most human) is full proof she’s simply outdone herself; that love of all colors is but a crippled symmetry.

[9]

Jesse Locke: Sarah Hennies’s latest composition is an exercise in balance, patience, and awareness. Keeping your mind deeply locked into its unbroken patterns of seesawing strings, low plucked notes, or metallophone chimes is a test of the listener’s meditative state and how long it takes to be lulled into mesmerization. Underneath these miniature movements by cellist Ashlee Booth and percussionist Adam Lion (the duo Two-Way Street), a thin layer of sustained notes snakes in and out like mist at the feet of a Halloween dance party, where attraction between two people could spark for the first time.

It’s tempting to read into the concept behind this piece and consider every element to be a musical metaphor. Early on in the 90 minutes of The Reinvention of Romance, the appearance of a piercing whistle tone created by Lion’s bowed glockenspiel quickly becomes abrasive. When a couple decides to move in together, the repeated solo behaviours that have long gone unchecked can turn into a source of annoyance. Shared existences may seem at odds until any pair develops compatibility, like a balloon on a bed of nails that doesn’t allow it to pop, or the ways these instruments deftly weave around each other in the composition’s final 10 minutes. Perhaps it could even be used as a new form of couple’s therapy for two musicians to play this piece from start to finish.

[8]

Jinhyung Kim: A couple of years ago, I read a book called Wittgenstein’s Mistress. The narrator, Kate, may or may not be the last person left on earth, but she behaves as if that were the case. She talks to no one—not even herself, really; she just transmits words into the ether. She tests out different signals in dry and procedural sequence, fixing or recalibrating them in the hopes of finding some resonant object, of getting back a response. It’s monologue chemically distilled, austere and absolute. It’s also deeply, unbearably lonely. I wish I could reach out to Kate, but I don’t know if I’d be able to get through.

On The Reinvention of Romance, it at first feels like cellist Ashlee Booth and percussionist Adam Lion don’t play with each other so much as transmit their signals in parallel. The piece appears to consist of isolated, self-moving automata, patterns whose iterative simplicity requires nothing more than for someone to press “start.” As a younger Wittgenstein might have put it: all one has to do is situate the “facts in logical space” (prop. 1.13), and everything will take care of itself.

In our world, however, the facts don’t take care of themselves. In the world you and I live in, romance (among other things) is an emergent structure, arising in subtle and oblique fashion from its parts. It’s not a direct consequence in the Cartesian void of logical space. Of course, this means it’s easy to forget the parts once you’ve got the whole. But… might that be the point of romance? For each person to shed their componential individuation and move toward a mutually inclusive state of being? I don’t know. It’s a way of losing yourself that has a certain appeal.

All I know is that Sarah Hennies rejects that definition. She finds romance in the vast, silent expanses of the Cartesian void. She puts together two voices whose isolation rivals Kate’s, and makes them… talk, connect, communicate. I can’t explain it, but I hear Booth and Lion listening to one another throughout the entire piece. I hear it in the spaces around and in between sounds. Even when only one musician is playing, I can feel the other waiting, listening. And when the sonorities of their instruments blend together, they still maintain the discrete boundaries of each. They don’t try to fill up the boundless space that lies between their voices—they just try to measure it as honestly as possible. There’s no pretense of dissolving into metaphysical unity, or converging upon a monologic expression of their collective essence. The commitment to dialogue between such empathetic yet resolutely independent actors in The Reinvention of Romance is what imbues all 86 minutes with an ever-renewing tension and vitality. It gives me hope: if I ever return to Wittgenstein’s Mistress, maybe I’ll find a way to talk with Kate.

[9]

Marshall Gu: My eyes couldn't help but roll a little two minutes into The Reinvention of Romance. With nothing else but a repeated non-harmony between the cello and percussion as advertised, and knowing that there was another 83 minutes of post-post-post minimalism to go, I guessed that these sounds would drone on for much longer. So I opened up my browser and researched more about Sarah Hennies and backtracked to Contralto, a similarly long work for strings and percussion, but at the heart of it, showcasing a number of transgender women speaking and singing, framing the listener's attention to their voices.

There's less on The Reinvention of Romance, quite literally. No viola, no violin and crucially, no voices, and thus, less of an emotional impact as well. I was right, by the way: the cellist and percussionist did drone on for much longer, followed by long stretches of atonality, silence, and a climax hammering on for ten minutes.

From the press info: “The Knoxville-based duo Two-Way Street (Ashlee Booth and Adam Lion) commissioned Hennies to compose ‘a very long piece.’” Wouldn’t it have been better if they commissioned her for an interesting piece instead?

[3]

Gil Sansón: Minimalism is often a test of endurance. At some point the listener has to come to terms with the fact the music isn’t going to change much. Some composers aim for the hypnotic and trance effect—as many in the first waves of the genre did—but Hennies aims differently, emphasizing endurance and tension so that when there’s a change in the music, it feels like relief. Repetition is used here along with a displacing of simple patterns, staying in one place but refusing to gel into a single ostinato. This way of working has the effect of making the listener think about the perceived subject matter, with the title seemingly implying the pitfalls of romance as well as the highlights, and how certain aspects of a person force us to adjust our personal parameters for the sake of acceptance and harmony. For me, this realization arrived with the bowed vibraphone; what was at first a tad annoying became as natural as an insect chorus at a summer night.

It’s reasonable to be skeptical about the inherent value of long duration music; a person may very well think that such a piece is more of a vanity project than a serious statement. In the case of The Reinvention of Romance, the duration feels necessary to make the point it needs to make, and the music is never less than fully engaging. Could this piece have been twenty minutes shorter and still be a strong statement? That’s debatable, I guess, but the cello and percussion live together here, exploring the musical instant in strong engagement, wisely employing tension and release to make the music breathe.

[7]

Sunik Kim: Ashlee Booth's cello sounds like waves (or, the gentle, regular creaking of a boat)—Adam Lion's percussion sounds like water (or, a reflection on the water)—for some reason I'm seeing the final shot of Straub-Huillet's Too Early/Too Late, where the camera plunges from the heights of a twin Egyptian skyscraper [under construction] to the depths of the river below; the buildings dissolve into a distorted mirror image of themselves, dispersed by the waves, which threaten to wash the monuments away altogether. The Reinvention of Romance is a duet, two forces moving in and out of harmony with one another; but beneath the placid surface of any great duet is a duel, an antagonistic back-and-forth with real stakes, real consequences—here muted, sublimated, but no less real:

Q: After the film people talked a lot about the end, the last shot. After the towns, after Cairo, after the countryside, come these two towers, skyscrapers, not built in the city but stuck down there by the water, like a threat to the countryside.

Huillet: For the first time I got an inkling of the story of the Tower of Babel, which I had always seen as just a Bible story, part myth, part piety, in other words not very interesting to me. And suddenly I got an inkling of the madness, of the hubris.

Q: So it’s what might happen to the countryside, or is happening.

Huillet: Yes, and one can’t tell whether the water, that is the movements of the water, will wash it away or...

Q: …whether the water will quieten down again and show it once again.

Huillet: So it isn't determined yet…

Straub: …who will win, whether it will be the hubris or the water.

[8]

Maxie Younger: Comfort is a complicated sensation, but its absence can always be felt. The Reinvention of Romance wears comfort like a snake wears old skin, bunching, ripping, tearing; moments of unease flash from beneath its surface, made all the more impactful by the piece’s minimal framework. Conceived as a reflection on the mutual, asynchronous care exhibited between two bodies in a shared space, the work opens itself up to further interpretation as it moves through dream-states of repetitive, intimate musical gestures.

The star of the 90-minute piece is the cello, from which each note is wrung like blood from a stone, sawing double-stops and chalky pizzicato reverberating, punching across the accompanying drones and percussion. Hennies takes care that these voices travel in parallel, never quite meeting. Although composed, the work channels the tensile, magnetic qualities of free improvisation: with each breath of silence shared by the performers I am left in suspense, made a hanger-on, waiting desperately for a continuation. The end does not feel like an ending: now, the everyday becomes the in-between.

Despite this, I find myself struggling with the work’s length upon relistens. Is anything being said in the 90th minute that isn’t said by the 60th minute? Do I listen to its conclusion out of a sense of obligation or out of genuine infatuation? Perhaps such a distinction is unnecessary, for I never resent the time this piece takes from me. When it finishes, I spend a few moments wallowing in its absence, unsure of what to do with myself.

[7]

Vanessa Ague: Sarah Hennies’s music is, in itself, reinvention. Her work explores gradual change: nearly undetected pitch shifts, steady rhythms with unexpected jumps. She finds hypnosis in simplicity, gleaning every possible drop of meaning from a note, a rhythm, or a melody, before letting it drift off into the ether. Immersion is often associated with the all-consuming, but this music is immersive in its gentle embrace of slow motion. It’s never too much—only just enough.

On The Reinvention Romance, Hennies places a cellist and percussionist in a conversation that delicately changes over time, illustrating the wavering nature of the relationship between two people who cohabitate. The piece begins with a fervor: the cello bows the same pitch with a robust confidence, and percussion interjects with vigor. There is a palpable feeling of anticipation, of excitement. But that assuredness slowly breaks down as off-kilter intervallic motion replaces expectation, and the uncertainty that lies beneath the surface is laid bare. Alarm-like, high-pitched ringing ushers in a new era of willowy drones and airy harmonics, of prickly plucked melodies and ticks like an out-of-sync clock. With just a cello and percussion, it’s a feat to travel through so many states—vibrancy, eeriness, warmth, iciness—and to move through them all with conviction.

The music is sporadic, but not without direction. Its ending emerges from a shroud of tension with radiance, glimmering with a newfound resonance as apprehension bubbles away. But as the piece reaches its final moments, anxiety begins to resurface. Those final, ascendant melodies remind us that rebirth is not devoid of its preceding states. As a whole, The Reinvention of Romance is an enveloping depiction of the undeniably human phenomenon of reinvention—one that uncovers the endless power of perception.

[10]

Average: [7.56]

Still from The Wild Reeds (André Téchiné, 1994)

Thank you for reading the thirty-second issue of Tone Glow. Spend some time with a loved one today :)

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.