Tone Glow 031: Sarah Davachi

An interview with Sarah Davachi + album downloads and our writers panel on Etrusca 3D's self-titled debut and Arurmukha's '14.11.90 (An Acoustic Psychogram)'

Sarah Davachi

Sarah Davachi is a Canadian musician and researcher currently based in Los Angeles. Since 2013, Davachi has released electronic and experimental music using analog synthesizers, organs, and more. Her newest album, Cantus, Descant, is a 2LP being released on September 18 via her own imprint Late Music. Jordan Reyes spoke with her on July 29th, 2020 via Skype about the expectations in being an artist, cowboy culture, plants, pipe organs, impermanence, and more.

Photo by Sean McCann

Jordan Reyes: Hey! How are you?

Sarah Davachi: How are you? Congrats on your recent nuptials!

Thank you. Yeah, we were very happy to do it, especially for immigration. My wife is going through getting her H-1B, and the process is supposed to finish in September. It’s kind of a rough time to be trying to get another visa, so we’re a little nervous about that.

I feel like they always run you through the stress just to make it harder for you. But I’m sure it’ll be fine, though that sounds really stressful.

Are you able to visit your family at all?

I don’t know, that’s the weird thing. It hasn’t been super clear what the regulations are like. I can go to Canada, obviously, but I don’t know if I can come back. And there’s nothing online. It just says if you’re a citizen or have your green card or whatever that you can, but it doesn’t mention other visas. So I’m not taking the chance of getting stuck until the border is open; they just keep closing the border and extending it.

I was supposed to be in Canada right now. I usually go in the summer for a couple of weeks to visit. I’m just telling myself it’s okay—I can go in a couple months—but I don’t even know if I’m gonna be able to go in December around Christmas, New Year’s. That’ll be hard. I don’t know how things are gonna change unless we have a proper vaccine. You have to believe that things are going to get better, whatever that means.

When the George Floyd protests started in general, it was hard to do anything. I’m already pretty glued to my phone, but during that time, the news made it worse in some perverse way.

Totally. It sounds extreme maybe but I was scared that if I got arrested I would have my visa taken away and be deported. I didn’t go outside and I was in the same boat—glued to my phone all day. When I woke up I would be lying in bed scrolling for a long time, which is probably not healthy, and I’ve been trying to be on social media less because it’s never been healthy. Part of me wonders whether the pandemic, and everyone being at home, and then being thrown into chaos lets out a specific kind of anger.

I think it did—so many people being without work meant they could go to protests. [My wife] Ambre did the same thing as you. She stayed at home for fear of deportation. I mean, they’re looking for excuses to deport anyone.

I hope tangible things come out of it. The world is completely fucked. We’ll see—I had a moment the other day where I said to [my partner] Sean [McCann] like, “Can you imagine in November if Biden gets elected and there’s a working vaccine?” Like, just the fact that that’s something you can imagine, even though it’s not likely to happen. I never thought I’d be elated at the thought of Joe Biden being president. I guess that’s where we’re at, the bar is so incredibly low.

What do people in Canada say about America right now?

It’s a bit depressing. Many seemed to think it was a problem confined to the US. I get that Trump is different from everyone else, except for maybe like Bolsonaro in Brazil. I’m not even sure what the right word even is for them. But there was this strange righteousness: “Look, Canada is such a better country and we’re so much more socialized,” and Europeans were saying the same thing. Canada has so many issues with racism, though, and Europe… I mean, are you kidding me? Europe has had a racist colonial mindset for centuries.

Whenever something bad happens in the US, it’s an excuse for Canadians to say, “See, look, we’re better than them” when they’re not really, and the horrible thing is that whatever happens in the US kind of fans the flames in Canada. Since Trump’s been president, they’ve had more problems with overt racist attacks, hate crimes. It’s like the US is just the loud uncle who keeps screwing up, and everybody can use them as a scapegoat. If people think that their city or country is somehow exempt it’s probably only because they’ve had the privilege never to experience it themselves. People in the US point to the South too, and that’s obviously not unfounded, but you drive an hour inland from LA and you’re in some weird republican hell. It’s everywhere. I think at this point the only thing Canada and Europe can really elevate is universal healthcare.

I’ve never been to Canada, but I’ve been meaning to go. I don’t know if [Davachi collaborator] Rick [Smith] told you this, but I have his EMS Synthi A here.

Oh, right, yeah. Are you using it at all or does it not work?

No, it works. I’ve been using it. I had an insane panic attack last week because I had put the copper routing pins in a plastic baggie I couldn’t find. I cleaned up my space a while back, which is when I started buying plants. And since I rearranged all the instruments and cords I thought I had tossed the pins by accident. The other day Rick asked me if the Synthi came with a manual. And I was like “No, I don’t think it came with a manual.” And then I was like, wait a minute, where are the pins? And suddenly I’m having a serious panic attack—“Oh my god, what did I do?” I texted him like “Dude, I think I lost the pins” and he’s like “You didn’t lose the pins,” and I was like, “Dude, I think I lost pins.” Eventually I found them.

It’s a weird stress—having something old and irreplaceable. I have this constant anxiety about earthquakes. I’ll just be sitting and think, “The big one’s gonna happen right now.” In every room I think, “Okay, I would go under that table.” But every time I walk into my studio, I just look around and I’m like, this is all trash if there’s an earthquake, and I don’t have insurance.

That’s a nice way to spend quarantine though—playing with a Synthi. Man, quarantine. So funny that that Thom Yorke show was supposed to happen in Chicago. I was looking forward to that too. Although I would have been so nervous—I don’t normally get nervous before playing, but that would have been ridiculous nerves. But I don’t have to worry about that now.

I’m sorry. Are you nervous in particular because the size of the venue do you think?

Yeah—those would have been by far the biggest places I’d ever played. I remember in February, Sean and I went to an LA Kings game. I was sitting there at the Staples Center being like, “Oh my god, this is the space. Like, I’m just gonna be standing right there in front of these people.”

What were you gonna bring to play?

Since the beginning of last year, I’ve been touring with a Nord Electro 6D and a bunch of pedals. There was a time when I was taking my Synthi on tour, which was ridiculous and too stressful. The Nord has everything I need and it sounds pretty good. And it’s easy to replace—if it breaks you can get one backlined right away. It’s not the nicest instrument visually, but for the amount of time that I was touring, it’s more important to have something that’s reliable.

Yeah, on my last tour I brought a Moog Model 10 with me, which is very heavy, and I just kept it in the passenger seat and buckled it in, but I was very freaked out about it.

It’s horrible—when I was traveling with the Synthi, I remember the exact moment when I realized I couldn’t do it anymore. I was on a flight from Seattle to Vancouver and there was nobody else in my row so I placed the Synthi on the seat next to me and buckled it in. And just as we were about to take off, the flight attendant walked by and said it had to go underneath the seat. So I went to take off my own seat belt to pick it up and put it under the seat. And she was like, “Oh, no, we’re taking off. You can’t get up. Just give it to me and I’ll put it down.” And I was like, “okay, it’s fragile, so just be careful” And she puts it in the next row on the floor and just kicks it under the seat. And I was like I can’t do this.

Do you mind flying?

I used to like it actually. In recent years, less so. I think it’s gotten worse—more cramped and more cutting corners and bullshit like that. Sometimes on longer flights I can enjoy having that time to myself. I don’t use the internet or my phone or anything when I’m flying. So having a stretch of like 10 waking hours without that can be really nice. But I got pretty burnt out at the end of last year. I was supposed to play in Brazil in December, and at the time I was waiting to hear about my American visa. I had applied, and was supposed to find out but they have to mail you the physical visa so you have to wait around for that until it’s official. And this was happening like a week before I was supposed to go to Brazil. I didn’t think it would come in time so I just canceled the tour. I was stressed about the process and burnt out from traveling, it was just too much mentally. But of course I didn’t know that I wouldn’t have been able to tour in the next year, so maybe I should have just taken the chance.

Do you miss it?

Yeah, one thing I miss a lot about playing live is traveling. That was the biggest perk for touring because I like seeing other places. I’m noticing now that the social side of me was also fulfilled through touring—I would see friends in other cities a lot and be an extrovert and then be introverted when I was at home. I miss performing but I know that will come back and I like working on records a lot so that keeps me happy for now. I don’t miss the chaotic schedule and the stress of worrying, and I think people are realizing that it’s not tenable to have a freelance career that relies on just one form of income—artists need to be supported without having to travel most of the year.

Do you think people are working towards that?

The Bandcamp fee waiver days have been a real eye opener. Artists are noticing that they can do their work, allow people to support it directly, and then make a tangible, meaningful amount of money. I think it depends, though. For me, I’ve been looking at grants. I’ve always been partly reliant on grants kind of on and off at different times, but it’s usually been additional money as opposed to a source of reliable income. I’ve also been looking into other avenues for music work at home. These things are mysterious, like film scoring for example. It’s a bit of a catch-22—you have to have all this experience behind you before opportunities come to you, but how do you get that experience if you’re not getting any opportunities?

But I can’t think of a single musician I know who likes the fact that all of their income comes from touring. I think almost everybody would like to tour a little bit less and have a healthier lifestyle at home.

Definitely. I had the same realization as you. Right before my last tour I started therapy—probably like three or four weeks pre-quarantine. I had been stressed out of my mind—in a very dark place. And since quarantine, I have had the chance to reconsider. I just was like, man, I can’t fucking do everything.

I was also diagnosed as high functioning autistic a few months ago, after starting therapy. Obviously a diagnosis doesn’t change anything, but it did make me reevaluate why I was doing specific things. The good thing is finding triggers. For me, interrupting tasks is a big one. If I’m doing mail order, and the doorbell rings, and there’s a mail person there and he’s got 200 mailers or whatever, it causes a big disruption to me.

It’s also made me reevaluate my day-to-day activity, and even communication. I can be like, okay, this is a symptom expression and I can find resources on navigating it. So that has been pretty eye opening. Now I realize, for instance, there will be something that my wife will say to me that I won’t understand completely—before I would have tried to come up with a response that doesn’t communicate that to mask it. Sometimes people say things or have a facial expression that I don’t really understand like a neurotypical person would. I’m realizing when I don’t understand something to ask for specifics.

Yeah, that’s not a bad thing—that’s just taking care of yourself. How old are you?

I’m thirty. I just turned thirty in May.

I’m sure this isn’t true for everybody, but I’ve spent the last couple years reevaluating my lifestyle, being in my thirties. I’m conscientious of the things that I care about—these are the things that I can give energy to, and these things I can’t. I’m not gonna pretend, and I’m going to be open about what I can and can’t do. In my 20s I would agree to more things. I think sometimes it comes out in touring. I’m a lot more open about what I need with my agents. Maybe it’s perceived as being more difficult, but if you’re just taking care of yourself, you can’t feel bad about that kind of thing.

What would be an example?

Hotels are one for me. For a number of different reasons—being a woman is just one—I don’t want to stay with somebody I don’t know. Not that I don’t trust the person, I just don’t know them and don’t feel comfortable. Or, knowing where I’m going to stay when I get somewhere. That really helps keep me sane when I’m traveling. Even if everything else is chaotic, I have this place that I can be alone and rely on as a safe place for my mind and body. I’ve been more forward with my agents—we usually just ask for a buyout and then I choose where I stay. That works well for me. Obviously you can’t do that in every scenario, but you should be able to ask for things that you need and not feel ashamed. It’s not sustainable to be uncomfortable all the time and it’s not healthy. I’ve been keeping some notes about more global touring issues that I think need to change. One of the things is understanding artists as humans as opposed to objects that get shipped from place to place to perform a particular function over and over again. The agents I work with get that and respect it.

Yeah, there is this thing about being an artist where you’re just supposed to be grateful to have the opportunity. You’re not expected to be assertive about your needs, and what’s fair. I mean, our work is devalued year over year, basically.

Oh, man, I remember when the pandemic first started—a few weeks before all the Thom Yorke shows were supposed to happen—within 48 hours everything from March onward was just gone. The majority of my income for the year was gone in two days. And I was reading posts online—people suggesting that maybe if you bought a ticket for a show, and have a job or whatever, you might not need the twenty bucks—maybe you could still pass it along to the venue or the artists who just lost their work. There were so many responses saying, like, “I didn’t get the thing that I paid for, so why would I just give somebody my money? If they want money for free, they can go on the street and panhandle,” and horrible ignorant shit like that.

Another weird moment with people talking freely online… so with the Brazil festival that I cancelled, I noticed that somebody posted about it on Twitter in Portuguese. I was reading the Google translation of it—they called me a slut and said that they wanted to drag me by the hair to the river for canceling.

Oh my god.

And it was a joke, I’m sure. But don’t they know they’re talking about a person? I didn’t publicly say that I was steps from a mental breakdown and benefited from canceling in that way also, but it doesn’t matter. You should understand that people have the shit they deal with in life. And be like, “Oh, I hope everything’s okay” when someone cancels something. Not like, “I can’t believe she did that. I want to drag that slut to the river by her hair.”

I think it’s a general thing of people expecting too much from musicians and not appreciating that what they do is work. Even streaming—the fact that people don’t understand how Spotify works is crazy, or that they somehow think people shouldn’t get paid for their work.

You know, it’s a weird gap in logic that exists.

Yeah. There really is.

Have you ever gotten a Spotify tip?

What do you mean?

Do you have that tip jar on Spotify?

Oh yeah—no, of course not. I set it up, like I put my PayPal email. No, I’ve never received anything from Spotify. I’ve gotten like months of income from Bandcamp.

Wow, that’s terrible.

I was teaching an undergrad class in Vancouver once, and I had mentioned being a musician on the first day of class. Afterwards we got into a discussion about it, and somebody asked about Spotify. And I was like, “Spotify is good for exposing you to different things, and it’s low risk to find out what you like, but one problem is that it doesn’t pay fairly.” And one of the students in my class said something like, “Oh, but why do musicians need to get paid?” Like, what? What do you mean? There’s still this assumption that art is a hobby. Art is something you do on your own time, whatever that means.

So, can you tell me about how you got into plants?

I can’t remember if I mentioned this to you, but I’m actually really bad at tending to plants. I care about them a lot, and I want to be good at it, but despite my best efforts, the plants I care for always die.

You did not tell me (laughs).

I’m not good at balance when it comes to that. I’m very much like, “I’m just gonna water it every day. And it’ll have all the water it needs, and it will be great.” Sean and I have a bunch that he waters and I prune, which I enjoy doing. And of course, they’re thriving. Plants have always been relaxing to me in certain ways, and I think it’s because they’re living. People don’t necessarily forget that they’re living things, but I think they’re not seen as companions in the same way as a domesticated animal. But they’re still living things that I think have an interesting—I kind of hate the word “energy”—but it’s an interesting energy to have around you. All of these things that are growing and decaying in space.

Yeah. I also hate the word energy.

But sometimes it’s just like, what else am I going to say? There is something intangible that comes from seeing them or feeling their presence.

I’ve got one like, right on my desk here, just a little guy (shows plants).

Oh, a spiky friend.

The day I got it I was bummed out or something, but that guy is unaffected. And it provided a little bit of resilience.

It’s something you can check in with, too. I have a plant in my studio that I tend to. I water it and Sean doesn’t touch it. And it’s doing okay. I’ll see it wilting, and I’ll know “Oh, you need some water. I see what you need.” There are very specific things they need. There’s something about that ritual of taking care of a plant—it’s a good way to keep perspective.

I actually learned a lot about plants from a friend of Rick’s years ago. I was housesitting for him for a while when I was in Vancouver. And he gave me very specific instructions about which plants need what, how often. One of the things that I thought was kind of interesting is that he had all these small ferns that needed to be watered once a week, but then I had to spray them with a spray bottle every couple days and that seemed to make such a big difference on them. Maybe that has something to do with that—the humidity where these plants are grown. Maybe they’re just used to a higher density of water in the air. I’ve been trying to spend more time outside too—hiking and stuff. My birthday is at the end of September, and the weekend before I’m going to go to the Sonoran desert for a couple days, which I’ve never seen. I’ve seen Californian cacti, but I was reading that Saguaros can grow up to fifty feet. I’ve been mentally preparing myself for seeing a cactus that big.

That territory—the Southwest—is so magical.

Yeah, I don’t really know it well. I think before I was in LA, I hadn’t found a place that made sense to me. I’ve noticed a lot more since living here that the openness and absence is meaningful. And I think that’s a hallmark of the Southwest. I feel like LA is where I’m going to be long term. It’s nice that you can get to so many places in a day’s drive. Sean has family in Utah and he’s spent some time in southern Utah—Bryce and Zion. They seem incredible. I don’t think there’s anywhere else quite like that. Foreigner is a weird term, especially for somebody who comes from Canada, but it’s weird to be a non-American and experience this country.

It’s also weird being an American with a non-American partner experiencing America. When Ambre and I first started dating I was living in this small town in Minnesota called Owatonna, which is an hour south of Minneapolis. When Ambre visited me she had never been to like a July Fourth parade. And there’s this little town—even smaller than Owatonna called Blooming Prairie—like one thousand people in the entire town. And they have the biggest parade in Southern Minnesota on the border of Iowa. She was like, “Your country is insane.” And she was right.

Yeah, the Fourth of July, so weird. There’s so much about America that’s bizarre. It’s really bizarre. I have become a bit more aware of cultural references I don’t get. Like before I moved to LA, I’d never heard of the band 311. And Sean grew up in Santa Barbara listening to Sublime and shit like that as a kid, and so he would talk about 311 and I didn’t know what that was. Or there are things specifically Canadian that I assume everybody knows about. Like saying “gong show,” for instance. It’s very—

(shakes head)

Exactly, yeah—I don’t know what the reference comes from. But when something is a total mess you’d say that it’s a complete “gong show.” It means that it’s like completely ridiculous and unhinged, you know? So I could say that like, “Oh, man, that meeting was a gong show.” Now I’m more cautious about it because people wouldn’t tell me they didn’t understand.

In college, there were a lot of people who got into Sublime and 311. I got into rock very late, though—when I was like seventeen I started listening to Nirvana and Bob Dylan.

Where did you grow up?

Well, we were living here in Chicago. But we moved around a lot. I was born in Newport Beach then moved to DC, then Chicago, and then I went to college at Duke in North Carolina. Then Chicago, and was in South Carolina, Miami, Minnesota, and then yeah, back here as of like, two and a half years ago. It’s been cool. A lot of different kinds of people. What places in the US do you want to go to the most that you haven’t been to?

I would love to spend a lot more time in the Southwest or just west of the Rockies. My parents live in Calgary, which is two hours north of Montana. I thought it would be nice one day to drive from LA to Calgary and go through Utah, Wyoming, and Montana. Texas, too—I have a lot of friends in Texas, and I’ve heard a lot of good things about certain places actually, especially about west Texas. The eastern part of the U.S. has such a different vibe and I’ve never felt super comfortable there. The cities and people are in such close proximity to each other. I’d like to spend more time there, though, even going to Washington, D.C. I’ve heard that Washington has a lot of interesting museums.

Yeah, you’d love it!

The city in the eastern U.S. that I like the most is Chicago.

Oh, really?

Yeah. If it wasn’t for winter, I would want to live there. Probably the only other place in the US that I would consider living, but winter? I’m done with winter. The older I’ve gotten, the more important weather has become. I lived in Montreal for about a year. And when I was in my 20s, I was like, “Montreal is great. It’s the best city. It has everything you’d want.” Coming from Calgary, I thought that I was okay with winter, but that year in Montreal, the winter was so horrible. It eats up a lot of your time, too. It’s a different sense of time in California. Time is just more loose because it could be December or it could be May. There’s no part of me that misses winter.

So you were born in Calgary, too?

Yeah, I lived there until I went to Mills. It’s the Dallas of Canada. It’s in Alberta, which is probably the most conservative province in the country. All the money there comes from oil and gas. It’s similar to Texas, and is steeped in cowboy/country western culture. They have a festival every summer called the Stampede, which is the world’s biggest rodeo. When I first moved to LA it seemed that there was a lot of interest in cowboy culture—the romanticized version. I appreciate things in country music, but growing up around the world’s biggest rodeo, I came to really detest that culture. I never understood the valorization of rodeos and cowboys.

Did you ever ride horses up there?

I had a lot of friends who did, but I never got into that. I grew up figure skating, actually. I did that for 13 years. I think horses need to be left alone. I always feel bad when I see them used as transportation. If anybody feels lukewarm on animal rights, being around a rodeo will change your mind—it’s the cruelest shit, for sport.

Like, when horses break their legs in the chuck wagon races, they’re usually just put down. They’re a racehorse, and if they can’t run, they have no value. Or when they do the bull riding, they tie off the testicles, which pisses them off. That’s what makes them buck. This is a very unpopular view for somebody from Calgary. It’s the pride and joy of the city, and in the week that it’s happening, the whole city is wearing cowboy hats and boots and all of that. You walk into a bank and there’s a bale of hay sitting there.

We had a lot of cowboy stuff growing up. I also used to wear a cowboy hat every single day before I went bald, and this is it (shows hat).

Oh, a Stetson.

Yeah it’s a Stetson! It was big in my dad’s family—his dad is Tex Mex, and his mom is Irish. In both Texas and in Tex Mex culture cowboys are big. So I grew up watching Clint Eastwood and Tombstone. I’ve always been transfixed by the cowboy, but it’s a pretty polemic figure. My next record is kind of country-tinged. It’s lap steel guitar, guitar, trombone, vocals, and keyboard. I was gonna call it Cosmic American, but then I thought maybe it could be read as nationalist thing, and especially in today’s climate, celebrating this American figure and all that’s emblematic of the cowboy felt questionable. And so I was like, well, we need to scramble this up a bit, and find a better interpretation—there’s one part of the cowboy that is supposed to dominate the land, animals, and “unwanted” people. And that’s the problematic aspect of it, but then there is a part that has to do with cohabitation.

I’ve kind of been thinking about that, too—about feeling comfortable in this geography and landscape. A lot has to do with Calgary being in the middle of the Rockies and the plains. I think the reason I feel comfortable in this part of the country is because I grew up in that environment, that natural environment. But then you’re like, well, what does that really mean? In one sense you’re the person who’s living in it, and you’re reacting to it naturally, but then putting it in the context of how different people ended up there?

My junior high and my high school in Calgary were both named after rancher/farmer type figures. And my junior high school was named after a Black cowboy—John Ware. You walk into the lobby of the school, and there was like a giant portrait of him and his family. He was very important in the history of ranching in Alberta. He was an enslaved American, and after the civil war he moved to Texas, learned about ranching, and then worked his way north into Canada. He’s the reason why ranching started in Alberta. And I remember thinking—because like I said, Alberta is just so conservative and a lot of the racism in Canada comes from that province especially—how surprised a lot of Albertans who take this pride in white cowboy culture would be to learn that it was actually a Black American who started that industry. And then I think about the fact that the high school I attended was named after a racist white farmer.

How many people live in Calgary?

Now it’s probably like 1.2 million. Something like that. It blows my mind that there are more people who live in California than there are in all of Canada. There’s the same number of people in Canada as in all of California as in all of Tokyo.

Oh shit. Yeah. Have you been to Tokyo?

I have. Yeah, I played there a couple years ago, which was my first time in Japan, which was like the greatest thing ever. I always think of Japan as being the country of the future. The social programs and city planning are so well done. I played in Tokyo in 2017. And then in 2018, I played in Kyoto, which was really different from Tokyo. Kyoto was the Imperial capital before Tokyo and so the architecture is older. I think it has the largest concentration of Buddhist temples in all of Japan. That’s a nice thing about being on the west coast—it’s harder to go to Europe than for people on the east coast, but it’s basically equidistant to Japan.

I hate flying.

There are ways to make it more enjoyable. I started doing a thing a couple years ago where I made a plan that for one flight every year, I was going to upgrade to business class, giving myself a nice experience to tide me over in my mind.

Yeah, I get really cramped too. I’m six foot three.

Are you, really?

Yeah.

You don’t look that tall in person.

I know—I have a bad hunch. I need to get better posture.

Have you ever tried yoga?

Not as much as I should. I need to do that and stretch. I was undergoing physical therapy for my back before quarantine, but obviously can’t be in proximity to other people. I got a bike recently and I’ve been doing that a lot. The thing about riding the bike is the same reason that swimming is so good. Same reason yoga would be good, too—you can’t look at your phone.

Yeah. I think people underestimate the psychological and intangible aspects of things like being able to be away from your phone. Exercise is good for your body, but mentally, it’s so helpful to be able to have that time to yourself and focus on something else. Especially right now. I used to do a lot of yoga, but kind of stopped when I moved here because my schedule was crazy with school. The last couple months I’ve been doing it a bit at home, but I actually bought a water rower. I don’t bike. I used to walk around a lot, but it’s hot, close to like 100 each day. So I thought I’d do this water rower and I really like it.

That’s a workout.

Yeah. And it’s the same thing where I’m using everything, both hands, so I can’t respond on a phone. I’m just in it, and the sound of it is so relaxing.

That’s amazing. I was on the rowing team in college. A friend was on the crew team and he was like, “You should try it out. You have to get up at four o’clock every morning, you’re on the lake at five till 7:30, and you get back for classes.” I was like undergoing an existential crisis, so of course I joined. I hated it, but did it for a year.

Do you think if you’d been able to just do it sort of at your own time you would have liked it more?

For sure. And I like using the rowing machine. For me if I am not physically active, I have a hard time maintaining equilibrium. So it’s nice to have that.

I got into the habit of being able to do stuff by foot in Vancouver. When touring went away, I realized how much I had relied on walking around, seeing cities by walking, and having that be a form of exercise. LA has so much variability.

I have a question about the pipe organs that you used for your new record. When you are getting acquainted with the pipe organ, do you have to kind of relearn the instrument a bit? Because each one is a bit different?

I wouldn’t say you have to relearn the instrument. This might be a boring analogy, but it’s like a car. All cars have the same functions, the same features. But when you get a new car, you have to orient yourself. I have a theory that I’ve been spouting for years that the organ is the original synthesizer, it works in all the same ways. Maybe that’s a better example than cars. All synthesizers have the same basic functions. They all have oscillators, they all have filters. You learn to play a synthesizer, but when you try one you’ve never played before, it takes some time for you to orient yourself. That’s what I like about both of those instruments—it’s like an individual. You have to spend time getting to know them. This is partly what I’m writing about in my dissertation. With a piano, becoming familiar with each is quicker.

Instruments like organs and synthesizers make sounds differently—they construct sound, they don’t necessarily have a sound that’s given to you. You have to actually create it, taking the time to get to know that sound. But what makes an organ different from a synthesizer is that organs are specific to spaces. They’ve been built for a specific physical acoustic space, and that has an equally important impact on how the resultant sound is going to be, getting a sense of the space and how the organ fits in. That’s not something you can do remotely.

On Cantus, Descant you use different organs in different cities—countries, even. Do you see the composition that comes out of each as singular to that place and instrument?

I think more so in certain types of organs than others. In the narrative of any specific instrument, there’s always—at some point—an effort to standardize, to make it so that when you play this piano, you can go to any piano, and it’ll be kind of the same. Certain instruments have evaded that for a longer period of time, and I think the organ is one of those. The organ that I played in Amsterdam, which is the organ featured the most on the record, made music you could only play on that organ. You could try to translate it to a different organ, but in my mind, why would you want to? It’s like meeting one person and then meeting another person and trying to make them the same, projecting. Why wouldn’t you just want to get to know the other person and see what they are and who they are?

I’ve always been a little bit anti-MIDI in my electronic stuff. I understand how useful MIDI is, and I don’t think that anybody is misguided to use it, but I like when instruments have a specific quality, when an instrument does one thing really well, and if you want something else, there’s another instrument, or another pedal. Also in my mind a produced sound is very closely connected to the act of playing, the physical dialog. In some cases, I wouldn’t even be able to figure out how to translate some things on the record to other organs.

There are certain compositional gestures that I was working out on many of them, though, and that overlaps a lot. I started working on the record in late 2017, and throughout 2018 when I was playing all these organ shows, I was figuring out what to say, and found myself returning to certain gestures, themes that I would explore on different organs. Those are things I would do if I were touring this record—things I would technically be able to play from the record, which is new for me.

What was it like playing on an instrument from the 1400s?

Well, the design of this instrument is from way before standardization was even a concern. It’s funny that we were talking about plants because it’s kind of a similar thing to organs. On that organ, the air is not electrically blown into the instrument—for the majority of modern organs there’s an electrical blower that blows air straight into the windchest and bellows, constantly. But with this one, there are actually four or five different pumps for the bellows. So there was another person who’s walking from pump to pump pushing them, tending to them, to get air into the instrument.

That instrument is the one that’s in all of the “Stations” tracks on the record. The way we played it, there are moments where the sound changes—where the person pumping is deliberately letting the air escape. It’s changing the harmonics, the air that’s left in the pipes and in the windchest. So in a way the instrument breathes—the need for air to be manually pumped in at regular intervals changes the way that it expresses. Modern organs are played completely differently, but this gives you a more direct connection to the entire instrument, not just the keyboard.

The organ tradition has had this move towards a less direct connection to the feel and mechanics of the instrument—like having the air electrically blown, or in more modern organs there are electromagnetic relays to connect the key to the pipe. That’s what allows pipes to be at the back of the church with the player sitting somewhere else far away—an electrical signal. When you hit the key it sends a signal to the pipe to open a valve and let air into it. But it’s on or off. The way that this organ that I was using works is less common—they’re called tracker organs. So when you hit the key and slide a particular stop out, it’s actually opening up the valve at a gradual pace, which means you can change the amount of air blowing through at any given moment.

And so when you were composing for it, would you write out the composition before? And then do like multiple takes or something?

The ones that were developed through live performances—those ones ended up being more scored. I knew specifically what I wanted when I went to record it. And those pieces were largely the ones I recorded with the Skinner organ in Chicago. I flew in the summer before my concert there to have four or five hours to work on the piece so I didn’t have to do it the day of the concert. And I recorded everything that I did that day and then set some time to record proper versions of those pieces.

I had already been familiar with the organ in Amsterdam from several years ago when I did a keynote speech at a pipe organ conference there. And that place is literally just a room full of organs. But I knew that I wanted to work with that instrument. When I went in to record, I basically just hit record and then played for several hours. We were experimenting with the bellows and just recorded everything. Then I edited that.

How do you record a pipe organ?

There are different ways—probably more professional ways than what I was doing. Some I just recorded with my Zoom recorder—actually, I had to because I was traveling. On others I was able to actually set up mics and do a proper recording. But even in those cases, I was doing a stereo room recording. There might have been one that was omni—I think the one in Vancouver was an omni recording. But mostly it was straight into my Zoom because I was on tour or something. I recorded one in Copenhagen during my soundcheck, which was in the middle of a tour. For me, it’s important to get the room sound—the harmonics happening in the room.

The Zoom is surprisingly handy when you’re in a pinch. I don’t think there’s such a thing as a right or wrong way to record. And it’s the same with any acoustic instrument. There are certain parts of the instrument—if you mic the bottom part of the cello, for instance, you’ll get different harmonics. And that’s amplified with organs because of the space they take up, both as the instrument and in a room. In Amsterdam, I had the recorder set up in the middle of this hall, recording the entire room, and I’m sitting right at the organ. And while I was playing it the air was coming out of the pipes straight in front of me, and it was the most psychedelic sound I’d ever heard, all those shifting harmonics. I never would have imagined an acoustic instrument from the 1400s could make that kind of sound on its own. With tracker organs you have to be sitting there right in front of the pipes, you know, and you’re going to hear it differently than anybody else in the audience and the whole time I’m praying these harmonics get picked up because that’s what I was so into.

So did you attach any mics to the Zoom for any of them?

I did on some—I would say half of the time I was using external mics. But I think the Copenhagen one and Chicago one were direct. It’s pretty forgiving when you’re recording in a room. If you’re trying to get close mics or very detailed recordings, maybe it’s not the best way to do it, but it worked well for my purposes. I like to think that I’m a little easy going about recording things, but I wouldn’t record something through an iPhone. That’s where I draw my line. I can’t go there in my mind yet.

And so the electronic instruments that you use—you have the Korg and use a Mellotron?

Yeah, and the Mellotron has organ samples on it, but I wasn’t using them—I just used orchestral sounds. At home I have the Korg CX-3, which is the only analog simulator of a Hammond B3. Technically it’s a combo organ since it uses oscillators, but it’s meant to sound only like a B3 and it has drawbars and a rotary effect on it.

And you recorded those at your house?

Yeah, I have my studio setup at home, which has been very helpful this year, especially—it helps my sanity to be able to work on music. I was recording all of the electronic additions at the end of last year, when I was in my dark visa hell. And this was cathartic, being able to hunker down in my studio and get to work.

What audio interface do you use?

I use an old Motu Ultralite. I’ve been meaning to upgrade it for a long time, but I’m very attached to the way I learned things, the instruments, and the equipment that I used while discovering my voice. I’ve had this Motu since like 2012 or something, and I use Logic to edit things. My version of Logic is actually a corrupt, cracked version of Logic 8. When I hit play, there’s this black bar that just covers everything. But it works fine. The functionality is fine. If it wasn’t functional, obviously, I would do something about it. But it’s just visual.

And when you were recording vocals you were using the Motu as well?

Yeah, I was using a nice condenser mic for the vocals but everything was just going through the same setup mode to my weird version of Logic.

And there’s a vocal effect, too?

Yeah! I’m glad you noticed that because I feel like not a lot of people are going to, but I’m very proud of it. I put a rotary effect like a Leslie on it, which is my favorite vocal effect. The first time I heard the Black Sabbath record Paranoid—

Yeah, exactly!

I knew it. I knew it!

There’s probably a handful of notable examples. But I remember when I heard that in junior high or something—that song in particular, and at that time I had an idea of what Black Sabbath was about, but then hearing “Planet Caravan” and being like, “What is this?” And the Grateful Dead actually do it a lot, too. There’s a couple of slow songs. But yeah—“Planet Caravan” was my reference point.

I saw Sabbath on their last tour, actually. They were amazing.

They’re such an important band and there’s so much in the production, even in Ozzy’s vocals. I like performing live, but I think of myself as being more studio-oriented. There’s so many subtle things in their production that you wouldn’t think make sense for a metal band.

I took a drive the other week right as the sun was setting, I decided I was going to drive to the beach. And so by the time I got to the west side, driving through Pacific Palisades on my way to the beach, it was completely dark, and I was just blasting Black Sabbath with my windows down smelling the ocean and the eucalyptus trees. When I got to the ocean I cruised on the Pacific Coast Highway for a while toward Venice. It was mostly dark and out the right window was just black. You can’t tell where the sky ends and the ocean starts. Just darkness.

It’s like outer space to me. When I was a teenager, I thought, “When I’m dead, I want my body taken to space and shot out into it. Float around.” I think now I see that as being lonely. Maybe too extreme for me. Maybe I should just be cremated and have my ashes scattered from a helicopter over the Rocky Mountains or something? There’s always been something about being small in the midst of the incomprehensible—like oceans, mountains, most of nature—in my music. There’s an idea behind some of the tracks—“Canyon Walls,” for instance, is this idea of… the way I feel about being inside of like a canyon is almost like nature giving you a hug. It’s very protected, very within this thing that’s much bigger than you in different ways.

It’s similar with plants, knowing that you’re both aging, you’re both living things that are changing and growing, but also dying continuously, but at different rates. And we’re these small things with a limited lifespan compared to the geography changing at an incomprehensible rate to us. But the fact that it still parallels the experience of impermanence—of things changing constantly—is interesting.

Photo by Sean McCann

Does that aspect of impermanence freak you out or it doesn’t bother you?

I’ve grappled with that a lot, and specifically on this record, it came into focus. This is a super personal thing that I don’t talk a lot about with the record, but in 2018, my mom almost died in a car accident, a really bad car accident. And she was fine, thankfully, but that shook me up for a long period of time. Your immediate reaction is “Okay, thank god, she’s fine,” but then you notice how it affects you psychologically over a longer period of time.

Fragility and impermanence are very weird. I don’t think they scare me—it’s just the way time works, the way that nature works. I’m intrigued by scale, of the way things can happen over a time period. I think it’s comforting. I remember reading somewhere that the function of a hymn is to comfort and allow mourning. And I thought that was so on point for what impermanence is because in a way, you’re grieving for something changing, something dying, and something going away, but you’re also celebrating change and you’re welcoming it. I think that’s why I connected so much with that specific organ in Amsterdam because of this quality. And because of this idea that they’re like living beings that are so specific to their environment, so specific that you need to tend to them in the same way you tend to a plant. Yeah, I think that’s a really interesting way of thinking about instruments. Especially because we don’t tend to think of instruments that way. We think of them as like tools, you know?

Yeah. That idea of upkeep to impermanence. That’s something unconsciously I knew because obviously, I water plants, but I hadn’t made the connection between that being the logical reaction to impermanence.

Yeah, I think that’s why I find pruning a comforting exercise because it’s like training my brain to see that like, okay, these parts are dead. But the whole living thing is still going—it’s still changing. You just have to tend to it in order for it to thrive.

How did you come up with the name for your label? Late Music.

If I’m being completely honest, Sean came up with it. I was doing that pipe organ conference in Amsterdam back in 2017. It was mostly people who were straddling the area between early music performance and contemporary music—new music for old instruments. So I had this idea to make a label where you pick an instrument and then commission five different people to make an album that uses new music for that instrument and release them as a box set. Every year focusing on a specific old instrument and having new music—that was the original idea of the label. And so when I was thinking about a name for it, it was a joke between us, like, “Oh, it’s not early music, it’s… late music.” And then I was like, well that’s kind of true. That’s kind of what I’m doing. It’s kind of what I feel like I’ve always been doing even with synthesizers to an extent.

Will you have other releases?

I’m holding on to that idea on a smaller scale. I was thinking maybe I would pick an instrument and then commission people to do a piece for that instrument and just make a record of all that with different composers, and maybe do one of those like every year or two years. I’m into the idea of doing reissues, too. But the initial idea with Warp [which Late Music is affiliated with] was to have a home for my stuff because I’ve jumped around so much with different labels. And I think because I put so much music out that it would be good to have a dedicated space for all that without having to worry.

I feel partly guilty, especially living with Sean [who runs Recital] and seeing how a label is run. Warp and my manager oversee mostly everything—I don’t have to worry about logistics or fulfillment. It is nice to be able to have a space to bring things together under a label umbrella.

Yeah, you don’t have to do mail order, do you?

Nope. I feel really guilty about that. I just help Sean with his.

For the ONO record that just came out there was an error in the vinyl master tracklist, and so I thought the track one of the B-side was on the final track of the A-side, and so when the thing came out, the center labels were wrong, and I was like, “Okay, either I have to get completely new vinyl masters, new master plates, and everything—which costs a lot—or I have to correct every single center label.” And I was like, “Okay, we’ll do this.”

But you know how most people would probably just like, take another thing and slap it on? Like, no, I actually cut out the track names from the extra ones, like the slice of solid color, put it and glue it on top of the incorrect thing and then I cut out the one that’s incorrect and put it on the bottom of the other. It takes so fucking long. Literally probably like 60 hours altogether. I mean, I will never make that mistake again.

Yeah, I feel like that’s how you learn about things. At least somebody like me. I’m a little bit stubborn. And it’s always like I have to learn it the hard way. But then you never forget. I do think listeners appreciate that kind of thing, though, even if they’re not being vocal about it.

Yeah, totally. Do you think about making more vocal pop-ish songs in the future?

The way I work is always that I have like three projects going on—three records that I’m working on at the same time. Right now I’m working on a new record that will probably have one song on it. And then the record that I want to do after that is probably going to be another double record, similar to this with organ, maybe some orchestral music, chamber music, and then the record that I’m working on after that and I’m in the very early planning stages of hopefully will be all songs. I feel like I have to start there. And then as I work on it, we’ll see. I imagine it won’t be entirely songs. But that’s the goal.

How far along are you on those records?

So the one that I’m actively working on I’m probably halfway through. I’m hoping to finish it by the end of the year. I’m just doing it all at home. And the other one—the double album of chamber stuff I’m planning in terms of what’s going to be on it. And I know what it’s going to sound like, but that one is a matter of going out and actually recording, which I obviously can’t do right now. But hopefully sometime next year I’ll be able to go out because I want to work with some people in Europe and have some organs in mind that I want to record. Whenever it becomes safe to go out and record, that one will probably come together quickly. And then the song one I put last because that one’s in the stage of like me sitting at my piano, you know, working out stuff. Very early stages of how songs might come together.

Are you nervous? Do you feel more like vulnerable by putting out songs like those?

Oh, yeah—I do in the sense that I’m not a singer. The keyboard stuff I feel like I can sit at any keyboard instrument and feel comfortable with it, even if I haven’t played it before. On past records I’ve played flute, violin, things I’m also not trained in but that I can kind of get by with, and I feel like the voice is not any weirder to me than those just in the sense that I don’t know what I’m doing. I feel more open to scrutiny or whatever. But in terms of songs, I mean, we’re actually releasing one of them as a single in like a week and that I’m pretty nervous about. But I think that’ll be like the first. And after that, it’ll be fine. Once they have it in their ear, I think it’ll be easier.

I love it. I love the vocal songs very much. I was hoping to hear you say that you were gonna do an album of them.

Oh, cool. I’m glad to hear it. At this point I know what people like of what I’ve done and what people don’t gravitate towards. And this—I have no sense of how people are going to react. But I guess it doesn’t matter in the end.

Photo by Julia Dratel

Purchase Cantus, Descant at Bandcamp.

Download Corner

Every issue, Tone Glow provides download links to older, obscure albums that we believe deserve highlighting. Each download will be accompanied by a brief description of the album. Artists and labels can contact Tone Glow if you would like to see download links removed.

Illusion of Safety - Water Seeks its Own Level (Silent, 1994)

It wasn’t until my interview with Jim O’Rourke that I learned that Illusion of Safety came out of Schaumburg, a suburb northwest of Chicago close to where I live. That project, spearheaded by Daniel Burke and involving various collaborators throughout the years, never seemed like an act I imagined would come out of a place I though to be so uneventful. It only made me appreciate their work more: Water Seeks its Own Level has the feel of a horror movie set in a suburb where everything seems a bit too nice.

The album begins with birds chirping, cars passing, a siren in the distance: the sound of a typical neighborhood on a random afternoon. But what quietly arrives is the sound of a wobbling synthesizer helmed by Jim O’Rourke, gaining traction until it becomes the only thing we hear. As it warbles incessantly, it suddenly tumbles into a vortex-like collage that spirals into a new locale that’s noticeably darker, more ominous.

As the album progresses, there’s a constant sense of unease: “Dissenting Voices” makes a fumbling industrial beat with the sound of electric currents; “Closer to Home” is glitched-up alien electronics, and “Even Lower” is primarily memorable for a high-pitched tone that’s played at length. By the time we hear field recordings, as on “Not Good” or “Rim,” they have a new veneer to them. Even when we hear a siren again on the final track (albeit, from a closer distance), it too has a sinister aura. Maybe there’s more to Schaumburg; all I know is that I’ll never see the town the same way. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

TD5 - Juvenile (Primate Recordings, 1997)

Primate Recordings was a DJ’s label from the start, specializing in bangers from big names that were fun to listen to and easy to mix with. Focusing on formula and popular appeal, they practically churned out 12 and 10-inches of workhorse techno during the era of rave culture’s biggest popular explosion and exported them far and wide. Because they aimed for popular coverage, Primate Recordings’s back catalog can now be seen as something of a museum to a former aesthetic norm in dance music.

TD5 was an alias of Melbourne’s Voiteck Anderson, a lifer in dance music who mostly shunned the spotlight when he was active, though his reliable history of banger after banger made him arguably the best ever techno producer from the Australian continent. While some are still rated highly by techno heads, most of the Primate Recordings catalog is now lost to obscurity. A 10-inch like Juvenile by TD5 can still be had for just a few dollars (plus the presumably ridiculous shipping costs) on the used market. While Juvenile was released to be formulaic fodder for mass entertainment, this in no way detracts from the music within. This is popular music not because it panders to any one audience, but because its primal simplicity allows it to be enjoyed by anyone who likes to dance.

This is minimalist techno in the sense of Robert Hood, not the European “mnml” that the next decade would bring; it’s emphatic and aggressive, designed to make you jump and move, not think or feel. Listen loudly and you’ll hear how its layers throb and move, sensing how physically hot and alive it can be despite its repetitive nature, an exemplar in how raw and pure techno can really be. —Samuel McLemore

Austere - Convergence (Sound-O-Mat, 1998)

I still remember being in high school, forcing myself to play Stars of the Lid during every after-school nap. While sufficient as a sleep aid, ambient music became far more intriguing to me once I recognized its ability to readily and wholly alter the mood and feel of any given space—my bedroom, my car, the school library I’d run off to after 5th period lunch.

Over the next couple years, I found myself transfixed by John Cage, EAI, and Wandelweiser. I discovered the way I engaged with such music was entirely different from my dabbles with drone: the hierarchy collapsed, the space I was in proving as crucial and replete with material as the instrumentation itself. Coupled with a desire to hear as much music as possible, I eventually found it easy to sleep to anything, be it punk, IDM, or—the album that solidified this for me—Pete Swanson’s Man With Potential. Sleeping with music was the same as sleeping in silence.

Enter Austere, an anonymous group of musicians who’ve created numerous albums across the ’90s and 2000s. Their album Convergence, which was inspired by Steve Reich’s ideas on process music (Reich is, by the way, a terrible person), was an album I stumbled upon only recently. It’s a single 48-minute piece whose first few seconds tell all; there’s nothing here but gossamer sheets of swelling ambience. The group’s anonymity bolsters the innocuity of it all.

Despite how Convergence is very obviously an album for sleeping to, I’ve always found its first dozen minutes infuriating. While the texture and timbre is perfect for feeling cozy, it moves just quick enough to keep me a bit too attentive. But as the album progresses, its individual layers coalesce into a beautiful mush, it soon becoming easy to let the music wash over me. Its my distaste for the album’s beginnings, however, that proves crucial in reminding me of my newly-formed habits: I can readily zone out to any non-ambient music nowadays, but when something that sounds sleepy comes on, I scrutinize how well it can get me snoozing. I’ve come to see these first dozen minutes as apt, mirroring the initial restlessness that precedes my sleeping. And as a result, Convergence brings me back to high school all over again: it’s one of few ambient records I feel I need to force myself to play whenever I want to nap. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Writers Panel

Every issue, Tone Glow has a panel of writers share brief thoughts on an album and assign it a score between 0 and 10. This section of the website is inspired by The Singles Jukebox.

Etrusca 3D - Etrusca 3D (Pacific City Discs, 2020)

Press Release info: Etrusca 3D is a new band that merges two current Audio and visual artists from the 21st Century, Francesco Cavaliere and Spencer Clark. The album is the first to be released by Spencer Clark’s label Pacific City Discs, as a subsidiary and in collaboration with Discrepant.

Etrusca 3D is the juxtaposition of two imagineers friendship, as Francesco says, “because I am Etruscan and you (Spencer) are 3D.” There is a piece of the future of Etruscan civilization contained within this disc. It is with Spencer’s remote viewing of a past and future creative culture and Francesco’s birthright that we find a true insinuation of civilizations world body.

We decided to invoke various Etruscan deities or spirits by sampling Francesco’s voice uttering their name. We put them inside the Emax 2 3D machine and we began to play these deities and thus incorporate a fresh and ancient music language to present the 21st Century Etruscan experience. In the meantime, these musical stories turned into Francesco’s imaginary storytelling style to further present a narrated record of the intuited activities of Etruscan Gods...’’

“One cannot underestimate the result of stating the names of certain gods at high voices. Something that sinuous and quiet enters into this disc for you to listen. What if the Etruscan Civilization instead of transforming or amalgamating into the roman one, was instead passed on to other worlds? Were the tombs, their spiral idols and funeral decorations a meticulous method for transmuting to something else?”

Purchase Etrusca 3D at Bandcamp.

Eli Schoop: You can be well-acquainted with Spencer Clark and not be ready for whatever he makes. Listening habits don’t prepare you for this. Music that conjures planets, unknown landscapes, concepts that don’t mesh well with the human mind. Maybe we should send this shit to space, it could credibly be more palatable to aliens. The closest analogue is writers making up a fictional language for a science-fiction property, but even then, it’s self-serious. Clark has no interest in complete immersion; instead, he reminds you of the uncanny. That’s his unfailing archetype, in that the listener can never be completely comfortable.

Etrusca 3D is not the most singular Spencer Clark release, but it builds on the foundation of his continuing mythos. Geometric balance is shifted constantly, confounding in a way that shakes our sensibilities to the point of stupor. What good is convention when it becomes utterly useless in the hands of a savvy composer? Even when Clark is recycling his most pertinent tropes, he is a true original. I personally have a keen familiarity with his work, but those who have not experienced the vast body of compositions will revel in such destabilizing sounds. By this creation, one can be indoctrinated into the Spencer Clark galaxy, a cornucopia unbeknownst to many.

[7]

Sunik Kim: When I hear this, I hear a substance that in turn coalesces and cascades in streams, provoking reactions and reacting upon itself, fracturing and disintegrating, vacillating between stability and instability. Cavaliere’s AutoTuned voice is the simultaneously malignant and live-giving prophet: the substance is his, but his powers are limited, and the substance always threatens to overpower him. When Cavaliere speaks, then, we hear threats hidden in protests hidden in incantations—or incantations hidden in pleas hidden in commands. In certain conditions (e.g. presence or lack of light), we hear a reversal of fortunes—we hear the actual moment of the tide turning—where the prophet either contains the substance or is contained by it. Etrusca 3D is a document of these constant reversals and overturnings; the end result differs with each listen and depends on external conditions (state of mind, sobriety, etc.)… It’s good, but I knocked it down from an 8 to a 7 as I wrote this.

[7]

Mark Cutler: Musically, the palette here feels much closer to Clark’s 2000s collages of worn-out world music, trippy new age, and tape-hiss for tape-hiss’s sake than it does to Francesco Cavaliere’s razor-sharp sound-art constructions. In a way, it feels like a timewarp back to 2008, like something you’d find in a Rapidshare link, a hundred-and-ten posts into a sharethread on 4chan’s music board, /mu/. That was the milieu in which Clark’s music really thrived, when weirdos disseminating weirdo music through the internet still felt exciting and mysterious, before the mass-professionalisation of ‘internet music’ through services like Spotify and Bandcamp. (Don’t get me wrong, Bandcamp in particular has helped channel millions of dollars to artists working totally outside the label/release system, including this writer and purveyor of deeply unpopular field-recording-based noise—but it’s hard not to feel that some individuality and mystique is lost when every artist’s discography has been arranged and presented in an identical, consumer-friendly grid.)

However, Etrusca 3D is both much clearer and more structured than Clark’s older, often side-long meanderings. True to its stated aim of envisioning a future Etruscan civilisation, the album constructs ritual chants from a mix of heavily vocoded, human voices, and the synthesized ‘voices’ you’d find on the ‘Choir’ setting of a mid-90s Yamaha electric piano. These sounds are familiar territory for fans of both Clarke’s solo output, and his work with one-time collaborator James Ferraro. However, there is a much greater sense of focus here; the voices here wrap around themselves until they form genuine hooks. Cavaliere’s own musical output sometimes has the hands-off tendencies of the more academic musique concrète, but he is thus likely responsible for the great precision and arrangement which make this one of the most accessible and immediately pleasurable records in Clark’s immense and winding catalogue.

[8]

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Etrusca 3D feels like a collection of vignettes, every processed warble and squiggling synth melody contributing to these pieces’ overall lightness. While I admire how queasy and dreamlike these songs are, it’s hard to shake the feeling that they could readily be the soundtrack for a film, or the audio accompanying an installation about the interesting subject matter. Frankly, whenever I feel a piece of art should be presented in a different context or medium, it’s hard to not have a sense of disappointment looming over the entire experience. But perhaps this points to another issue: these songs feel too loose, too ephemeral to stir up anything beyond initial intrigue, all of it eventually dissipating. There were far too many moments where I thought to myself, “Is this it?”; When something constantly feels incomplete, I can’t help but be annoyed.

[4]

Gil Sansón: Why do so many experimental musicians believe that a clever concept is enough to merit interest in a piece of music? After all, clever concepts aren’t that hard to come by. Interesting and affecting music is much harder to conceive, which doesn’t mean that all music should be painstakingly labored into being. You can have both: strong music reinforces a good concept. The concept here is that verbally invoking the names of Etruscan deities can somehow bring them to life in this digital time. “3D” in this case brings to mind printing objects from a digital file, which makes me wonder: why stick to a sound palette that sounds so hopelessly like mid-to-late ’80s MIDI when today’s technology allows for far more precise replication of the original?

It sounds immediately outdated, and I’m reminded of a phrase from a review of Robert Wyatt’s Cuckooland by Clive Bell: “digital halitosis”. Also, the record doesn’t sound like more than a few hours were invested in it, whatever came first deemed good enough for release, with the artists giving each other high fives along the way, which makes me wonder about the sincerity of their intentions. It’s like a bad TV soundtrack from the late ’80s—I can imagine the corny special effects that’d serve as its visual counterpart.

Not that I’m concerned about the opinion of ancient cultural artifacts and myths, but I can’t see how ancient Etruscan deities would be pleased to be turned into cheap plastic objects for public consumption in the name of art. Again, maybe the artists really like their cheesy synthesized trumpet sounds and believe in what they do. To my ears the result is at best laughable and at worst cringe-inducing.

[1]

Average: [5.40]

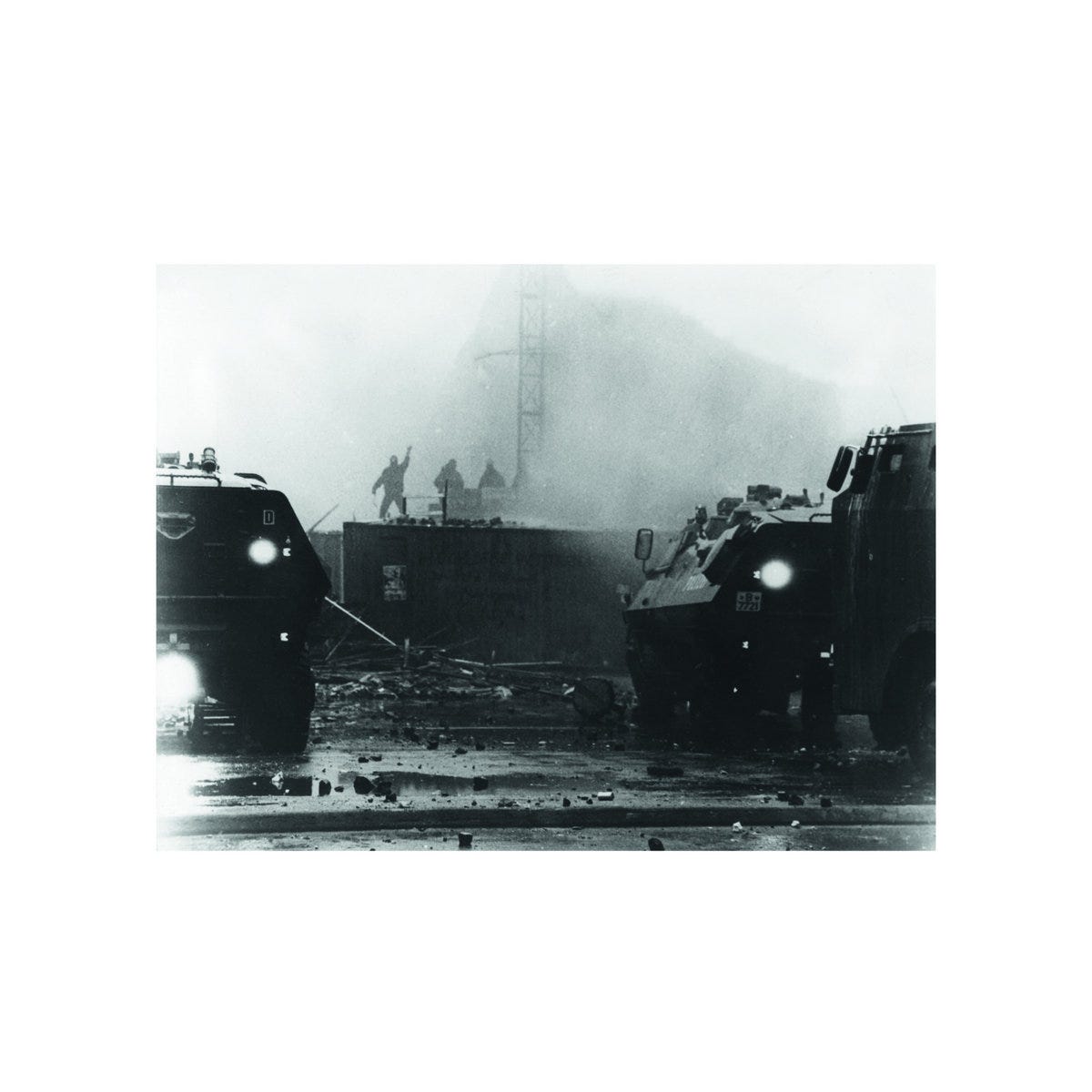

Arurmukha - 14.11.90 (An Acoustic Psychogram) (Karlrecords; 1993, 2020 Reissue)

Press Release info: Re-release of the album which Marc Weiser (Rechenzentrum, zeitkratzer) and Jürgen Hendlmeier (producer for The Flaming Sideburns, Thee Ultra Bimboos) created as Arurmukha. With the use of soundbites, field recordings, and stylistically diverse tracks, they reprocess the eviction of 13 squats on Mainzer Straße in Berlin-Friedrichshain in November 1990, forming it into an acoustic scenography in the style of the “Maifestspiele” by Einstürzende Neubauten.

14.11.2020 marks the 30th anniversary of the clearing of 13 squats on Mainzer Straße in Berlin-Friedrichshain. The violent confrontation between the police and about 500 squatters, involving armored vehicles, helicopters, and ten water cannons, was the biggest police operation in Berlin's post-war history, with 4000 officers deployed, and is deemed to be the last big “battle” of left-wing squatters in Germany. On the occasion of the anniversary, the Berlin label Karlrecords is making a contemporary document that has been out of print for more than 25 years available to the public again.

The album 14.11.90 by Marc Weiser and Jürgen Hendlmeier was originally released in 1993 as a vehicle for them to work through their personal experiences as contemporary witnesses of the eviction, on the label Goldrausch-Tonträger, which was founded for the release. The project's name, Arurmukha—“avaricious demons,” is a term from Vedic mythology, here alluding to the capitalist logic of exploitation guiding the West German corporations that bought out the former GDR after reunification. Shunning the popular clichés of squatters, the duo processes original recordings of the clearing action, as well as material from radio and TV as their musical-textural starting points, composing them into a densely packed acoustic psychogram, recounting the events of the time with dramaturgic skill, in chronological sequence over the course of the two sides of the vinyl.

Armed with a sampler as their main instrument they create an acoustic scenography which, as a sonification of memory, pits itself against oblivion. While constructed as a soundtrack, the heterogeneity of its styles gives the album the character of a compilation, aggregating drones, industrial, electronics, post punk, outsider music, and political texts into an imaginary meta music film of resistance.

Purchase 14.11.90 (An Acoustic Psychogram) at Bandcamp.

Matthew Blackwell: The first track of 14.11.90 begins with the potted musical intro of a local news program and ends with the sound of a pig being slaughtered. This is a nice summation of the album’s purpose: as an “acoustic psychogram” it’s meant to cut through the official media account of the confrontation between squatters and police in Berlin’s Mainzer Strasse in November 1990 (the porcine squeal leaving no doubt as to the musician’s sympathies). The next 45 minutes are a collage of different musical styles along with news reports and field recordings of the event.

The first proper song, “Tanz auf dem Vulkan” (Dance on the Volcano) is unfortunately and misleadingly bad. A martial drumbeat provides the background for very early ’90s rap-pop vocals, with very late ’80s electric guitar stabs interrupting at times to ghastly effect. But for the intrepid listener who keeps with it, the rest of the album is by turns affecting and musically sophisticated, only rarely lapsing into this unfortunate production style so common to the era. “Schwarzer Montag” (Black Monday) is built upon field recordings of the scene on Mainzer Strasse, with police instructions amplified by megaphones and responses shouted back from squatters. Distant horns are the only hint that this is more than a raw recording, until they are joined by increasingly loud drums and, finally, dissonant and angular guitars. “Weine Nicht, Mein Kind” (Don’t Cry, My Child) is a slow burn that incorporates audio of a woman crying into a drums, organ, and trumpet dirge. “Wir Warten auf’s Kristkind” (We Await the Christ Child) takes what sounds like a siren and gradually transforms it into a whimsical—and possibly taunting—lullaby. “Vakuum” (Vacuum) takes slowly shifting synths and overlays camera clicks and a radio announcer’s narrative of the police conflict. The last song, “Trans-zen-dental” should by rights suffer from the album’s occasionally cheesy production style, but instead pulls off a heartfelt and hopeful final note.

For an English-speaking audience, there is much here that simply doesn’t translate, either linguistically or culturally. The German-language field recordings, news announcements, and lyrics provide contextual clues that the album is about a newsworthy event, but unless the listener undertakes quite a bit of outside reading, the specific circumstances remain obscure. However, as every day sees new clashes with police on the streets of almost every major American city, it’s worthwhile to takethetime and see how this event can shed light on our current politics. The fluid situation created by the incursion of West Berlin anarchists into East Berlin after the fall of the Wall does not have a direct correspondence to today, of course, but temporary holdouts like the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone have much more in common with Mainzer Strasse than not. Perhaps most importantly, 14.11.90 asks us to think about how such situations are represented in the media. Its successes and missteps can teach us how to make a document of this time that speaks beyond this time, speaking back to official news sources in the here and now while remaining culturally relevant 30 years into the future.

[7]

Sunik Kim: A whole album of songs as strong as “Trans-zen-dental” would be something else entirely—but that's not the point here, at all. Is an album ‘about’ a historical tragedy—especially one bulldozed by capitalist myth-building and amnesia—by necessity ‘good’? (A similar, though not exactly identical, question would be: is an album 'about' a personal tragedy by necessity good? Or, is it ‘morally’ wrong to dismiss or dislike a piece of music informed by tragedy—regardless of its form?) I’m not sure; and I think the answer gets at fundamental questions of what music ‘is’ or ‘does.’

A very cynical reading of music is one of pure function: music exists to create a certain emotion in me. All music is then categorized by the specific mood it engenders (‘happy music,’ ‘sad music,’ ‘exciting music’...) This is undeniably a big part of the listening experience—but I think we can agree that there’s something more to music than pure function. A ‘sound-document’ like 14.11.90 also serves a function: in this case it’s a reminder, a retelling of an event, a literal piece of history. How can one place a piece of history on an (aesthetic) scale of ‘good’ or ‘bad’? It exists for itself, and doesn’t really give a shit whether you (again, on an aesthetic level) 'like' it or not.

I tend towards evaluating music at face value, or purely as it exists as music, and often only take context into account as an extra. On that level, 14.11.90 is...fine. Stripped of any historical context, I honestly wouldn’t spend too much time with it; the ‘post-punk sound collage’ as a form sounds a bit dated in 2020, and its ‘soundtrack-documentary’ quality by nature implies that the music is just one part of a larger whole—the listening experience is by definition incomplete, and therefore not totally satisfying (like listening to a film soundtrack).

The historical context doesn't change my opinion on the music at all. But it does affect how I evaluate this ‘thing,’ this ‘document,’ of which music forms a large component. I see its importance: it pushed me to learn about something I had never heard of. OK—the function has been successfully carried out (I consume this sound-document and am educated, regardless of whether I like the music; I consume this piece of ‘happy music’ and now I feel happy.) Nothing too wrong with that. But, ultimately, when a song like “Trans-zen-dental” bursts through the documentarian muck, I hear the dazzling power of a ‘unified,’ expressive (not reflective) sound-document, one that channels, multiplies—through incredible music that stands on its own, and is only further heightened by (rather than totally reliant upon) context given via press release, snippets of news and field recordings—the storm of pain, grief, hope, feeling, that drove the mass political eviction and protests in Berlin-Friedrichshain, November 1990.

If music is anything, it is a concentration (ten feelings in one, ten feelings at once). Rather than a chronological laying out of the event on the page, more-or-less neatly, as occurs for most of 14.11.2020, a concentrated amplification of feeling—maybe even beyond the point of ‘historical accuracy’—as we can begin to hear on “Trans-zen-dental,” could have pushed this piece of history into a realm far beyond mere document, mere retelling, mere soundtrack accompaniment. I usually try not to make ‘what-ifs’ when reviewing music, but in this case I’m giving in—a whole album of songs as strong as “Trans-zen-dental” would be something else entirely.

[6]

Gil Sansón: From the get-go there’s a sense of actuality present: a newscast transmission is sabotaged by direct action, militaristic drum programming and a defiant attitude. Despite the dated sound palette, it still sounds urgent, the menacing droning and the megaphone voices opposed by drums and chanting; there’s a sense of impending confrontation felt here three decades after the fact. Truly, this is rock in opposition to the system, going beyond the slogans and sing along choruses: it’s music as a weapon of resistance.

For anyone who has experienced civil unrest, urban barricades, tear gas and police violence, this album will bring raging memories of political systems in full repressive mode, devoid of the mask of civility. Of course, the context here is particular and the music reflects it: there’s heavy use of darbukas and other middle Eastern percussion instruments to represent cultural resistance, it then mixing with the sounds of street violence, radio captures and somber melodies on electronic keyboards (this last element is the one that firmly dates the music to its time). 14.11.90 has a really good flow, every minute retaining a sense of urgency and anger, but also hope—plain old hope in the face of injustice, when everything seems lost. The documentary nature of some of these tracks remind the listener that this isn’t music for music’s sake: this is political music.