Matmos

Matmos is a Baltimore-based duo made up of Drew Daniel and M.C. (Martin) Schmidt. The two have been making conceptual cut-up computer music for over 20 years with critically acclaimed albums like A Chance to Cut is a Chance to Cure (2001), Supreme Balloon (2008), Ultimate Care II (2016), and Plastic Anniversary (2019). The duo’s new album, The Consuming Flame: Open Exercises in Group Form was made with the help of 99 collaborators, including artists such as Yo La Tengo, Oneohtrix Point Never, and clipping., who were all given one instruction: The music must be 99 bpm. Sam Tornow chatted with Matmos over Skype on August 14th, one week before the album’s release. They discussed the scope of the project, music created by a UFO cult, the duo’s past teaching careers at the San Francisco Art Institute, and more.

Sam Tornow: Hello!

Drew Daniel: Hello! Is this Sam?

Yes, this is Sam.

Drew Daniel: Can you see and hear us?

Yes I can! Here, I can turn my webcam on, too.

Drew Daniel: Great! Otherwise, we’ll just be looking at ourselves the whole time, which is vainglorious and narcissistic, and an interview about your own music is sort of narcissistic enough, I think (laughs).

Well, to be completely honest, in these Skype and Zoom meetings that are happening more and more, I spend too much time looking at myself, fixing my hair, etc.

Drew Daniel: Well, I think we all look great! I have lowered my seat, so that it’s the same height as Martin’s.

Martin Schmidt: And I’ve lowered my expectations.

Drew Daniel: He’s 6 foot 2, and I’m 5 foot 8, so you shouldn’t be fooled by the fact that we seem to roughly be the size.

OK, I’ll take note of that.

Martin Schmidt: And speaking of fucked up optical illusions, what is with that map [on the wall behind you]?

I’m sitting on my bed with my computer also on the bed, so this (lifts computer up) is eye level.

Drew Daniel: Ah, okay, okay—

Martin Schmidt: Whoa, whoa, whoa, now I see.

Drew Daniel: We thought you just had some fucked up parallelogram map that—

Martin Schmidt: Which I was like, that is fucking cool, but then when you moved your head, the other frame is perpendicular. I was like, OK, that’s probably a lens, not a really fancy framing job.

Drew Daniel: Things are slanted and enchanted.

Yeah, usually when I start these Skype interview calls, I’ve started so many of them where I’m the one whose webcam is turned on and the artist usually has their screen turned off. So I wasn’t preparing to have mine on, but this is completely fine.

Drew Daniel: We don’t really have anything to hide about ourselves. We’re not young and hot and cute, where there’s like some big visual sell, where you’ve got to live up to some standard.

Martin Schmidt: We are ugly old men.

Drew Daniel: Yeah, we’re old hags, who gives a shit (laughs).

Martin Schmidt: So, really, is that a thing where artists are like, no pictures or videos?

I’ve started plenty of interviews where I will be the only one with my face showing. So, I feel like, from an interviewer’s standpoint, that’s a little awkward, but I’m the one asking the questions, just staring at them and getting no visual cues back. It’s happened five or six times now.

Drew Daniel: Well, we’re on a level playing field here, so let it flow.

Perfect.

Drew Daniel: So, how’s it going? Hi, how are you?

I’m doing great! How are you?

Drew Daniel: I’m alright. I—

Martin Schmidt: Where are you?

I’m in Chicago right now.

Martin Schmidt: Okay.

And you two are in Baltimore, correct?

Drew Daniel: Yeah, we’re in Baltimore right now. We just got back from going to Pennsylvania for a few days to get away from the humidity and cool down. We stayed in a little house in a national park, where there were also some Frank Lloyd Wright houses like Falling Water. So now we’re back home, surrounded by all this crap. It’s nice to go away and realize you don’t need all this stuff. It was like a weird little taste of what our lives used to be like before quarantine and lockdown.

Martin Schmidt: We went away all the time.

Drew Daniel: Yeah, we used to go away all the time.

Where in Pennsylvania did you go?

Drew Daniel: It’s a place called Ohiopyle.

Oh, okay.

Martin Schmidt: You have not heard of it, have you? (laughs).

Yeah. I have family in Pittsburgh, so I’ve spent a fair amount of time in the state.

Drew Daniel: Yeah, okay. It’s definitely got a yinzer vibe to it.

Martin Schmidt: It’s sort of exotic to us, because for the first seven years we lived in Baltimore, whenever it would fall to me to go somewhere out of Baltimore, I’d think, Oh God, I live in Maryland. What even is that?

Drew Daniel: How did that happen?

I was just having the same conversation with my partner the other day. We drove out of the city, and I was thinking to myself that I’ve lived in the city for over a year now, and I don’t know anything about Illinois.

Martin Schmidt: Exactly! What is it! We have the same thing going for us. I could say the same thing about Illinois. My dad went to high school in Evanston. So I’ve been there, and creepily enough—I mean, my dad was well old when he was alive, and he’s been dead for many years now—but there are plaques in the high school for him. I was like, who saves these? I mean, there were plaques from like 1933, which is kind of cool, but also, kind of weird. I wonder if they’re there anymore?

Drew Daniel: Your dad is canceled.

Did you plan to go on a trip the week before the album comes out?

Drew Daniel: No, it just kind of worked out that way. I’ve been working like crazy on an academic manuscript. I knew I wanted to have it done by my birthday, which is in July. We wanted to travel sooner, but with flare-ups of the disease popping up, it never seemed like a good time to travel.

Martin Schmidt: We were going to go to California—

Drew Daniel: Yeah, we had a lot of plans. We were going to go to London. I bought tickets to see Current 93 in London in June. Everything just got completely scrambled and turned around.

Yeah.

Drew Daniel: It is kind of weird to talk about this record in the context of quarantine and lockdown because it was made before that was a reality. But it was made under conditions that match up with how people interact now, like long-distance recording sessions. There were a few recording sessions where we had people together playing at 99 bpm. Martin did those about a year and a half ago in Italy.

Martin Schmidt. Yeah, this was a weird one. I had made some things in Italy, like I jammed with this improv jazz group in the studio.

Drew Daniel: It was Squadra Omega.

Martin Schmidt: So, we had these kinds of backing tracks. The drummer is the drummer for Lower Dens, and we were like, we have no idea what your drums are going to go with. Half the time he’d just be playing to a metronome, and we’d say, now play jazz!

Drew Daniel: Chacha! Now give us a krautrock groove. Luckily, he was fine with it. Sometimes Martin made weird collages of these Italian recording sessions where it was like 20 minutes, and it kept meandering into different styles, and Nate [Nelson] would just have to play along. Then we took that, chopped it up, and manipulated that. The record is, at times, a mixture of improvisations, jamming, that gets recomposed, and then another artist had to respond to it.

Martin Schmidt: But very little.

Drew Daniel: Virtual bands just sort of crystallized and—

Martin Schmidt: You know, I had something I was pursuing there, Drew (laughter). I know it sounded like meandering. My point was that very few people knew what the other collaborators were playing. He was like, I have no idea what my drum tracks are going to wind up on. It ended up as an exquisite corpse. Where you have a hint about what your recording will sound like, but then we took a bunch of corpses and collaged them.

It’s like a Matmos Frankenstein’s monster.

Drew Daniel: Yeah. I like that virtual bands would crystallize out of the layers of mediation. So, for example, David Grubbs sent some guitar, which I chopped up and combined with unrelated percussion from Sarah Hennies, then I brought in Owen Gardner and had him play guitar along with the chopped up Grubbs recording so that the tunings would work, but then I had him do multiple tracks, and I took some of those tracks, relocated them and synced them with some Jew’s harp, and brought in Bonnie Lander to sing country vocals along with the guitar that had been played along to the thing that had been removed.

We just kept holding up one layer to another as a template and then peel it away, and overlay more stuff. We feel like it’s a compilation of a ton of bands that never existed but could exist, you know?

Yeah, absolutely.

Drew Daniel: So it’s like, what would it be like if Sarah Hennies was playing with David Grubbs, or what if clipping. was jamming with Twig Harper, what would that be like?

Martin Schmidt: Nothing like this probably.

Drew Daniel: Probably not, yeah. It’d probably be cooler, but this is what we made.

One of the things that struck me during my listens of the record was just the sheer organization that had to take place to make this happen. It’s difficult to get three people to settle on a movie, let alone this.

Martin Schmidt: Yeah, It was sort of a nightmare.

Drew Daniel: There was a cat-herding vibe at times, and we got confused about who’s on what section.

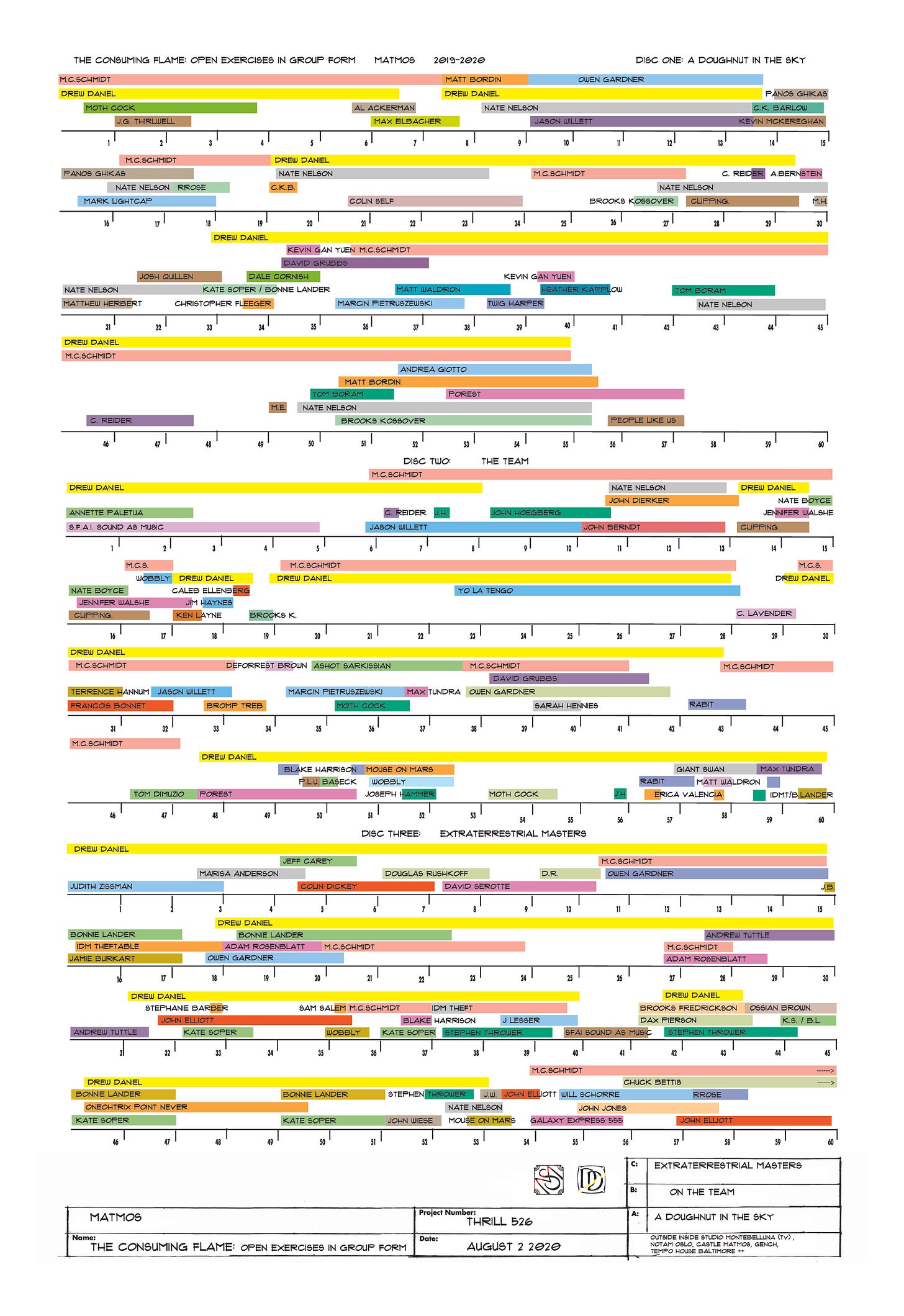

Martin Schmidt: And the poor record label, this has been some weird exercise in what music is now and what you have to do for Spotify, particularly, the weird thing that so many people aim at, and yet, pays us nothing. In essence, you must, when you make your three-hour album, slice it up into little songs, and we were like (makes caveman groaning sounds), so we were listening to the thing and were like let’s just slice it there and there. That took a couple of sessions of four or five hours. Then we had to name the sections. So we named them these fucking things, and then the label calls us later and is like, “Okay, so on ‘Goodbye Love Boise Eye Card,’ or something, who plays on that?” And I was like, what is that?

Then I made that chart, but of course, the chart doesn’t have the songs. At first, I thought the chart would be useful, and then I realized, oh god, it’s not useful at all. It makes it even more confusing.

Drew Daniel: Yeah, that’s a problem. Culture wants bite-sized pieces that are songs, predicated on the idea that songs are an expressive idea-driven distillation of an artistic mind that had a concept and then executed it. So there’s this causal chain that’s based on real emotions, sincere artists, individual auteurs, but everything about this record ignores that architecture.

Martin Schmidt: And 7-inch singles.

Drew Daniel: We made a three-hour relay race of 99 people where nobody ever sat down and imagined these as songs, and I didn’t think of them as songs, ever. They’re not songs. They’re overlays of templates of materials. That’s the whole fun of open exercises in group form. Group form is supposed to be what emerges collectively when people all put a little in, but nobody’s too much in charge. But the retroactive process of making a cut, giving it a name, I understand and respect that people don’t have three hours or just want to use a handle to pick up the part they like, but that’s just not the way we went about creating this.

Martin Schmidt: It’s been hilariously confusing.

Drew Daniel: It’s been a fun, confusing thing to try and to understand.

It confused me while listening. The first track is called “A DOUGHNUT IN THE SKY,” but I think the sample that says that phrase is on the third track. I thought I had all the tracks mixed up.

Drew Daniel: (laughter). There are certain phrases that keep repeating across the whole album, like a slogan or leitmotif. It’s supposed to be cumulative and give the listener a “How did I get here?” feeling. That’s something we really want the listener to have.

Martin Schmidt: So, in a weird way, my confusing poster is even better because of how confusing it is. You’d have to be listening to the CD and watching the time elapsed, and go, “Okay, this is 22:30, so that’s Moth Cock.”

I like that the chart so closely resembles the “Member History” charts on Wikipedia pages for classic rock bands.

Martin Schmidt: (laughs). Well, the space we occupy in music is so obscure, and yet, not so obscure, so I loved the idea that it looked like that. Especially since we have participants like a 14-year-old boy who made something on GarageBand because Drew wrote to his father, who is a writer, and he was like “My son makes things! So I’ll have him do something,” and they sent us this, and we were like, “Oh, okay.”

Who is that?

Drew Daniel: He’s a math professor, his son, Caleb Ellenberg is the one on the record here, and he’s 14, I think. The dad is the author of How Not to Be Wrong, Jordan Ellenberg.

There’s also some like UFO-related content on this record. Neither Martin, nor myself, have had experiences or—

Martin Schmidt: I’m down, though, don’t get me wrong.

Drew Daniel: “I saw a doughnut in the sky” was a phrase that C. Reider put into some speech synthesis program and had the voice say it. He sent it to us, and we just liked the phrase. Then, Colin Dickey, who’s also on the record and is a historian that wrote the book The Unidentified, which is about people’s desire for unexplained phenomenons, and what is behind the cultural desire for something that can’t be rationally explained. So we just followed an intuitive, water-course way, like “C. Reider gave us “doughnut in the sky,” Colin Dickey is a kind of ufologist, and then these families of collaboration emerge.

Martin Schmidt: The successive phrase “I am an extraterrestrial master,” which perhaps you noticed comes up a few times, probably too many times.

Drew Daniel: Yeah, I didn’t realize, it’s on side three a lot.

Martin Schmidt: Yeah, there’s maybe too many.

It certainly adds to the “how did I get here,” experience.

Martin: Good! Nice. We got a cassette, it may have been from my sister, who was an unreconstructed, real hippy. She gave me a bunch of cassettes at one point which were just fucking magical, and one of them was of this UFO cult, like a new-age group—

Drew Daniel: I think they were channelers—

Martin Schmidt: And the entire cassette is people saying, “I am an extraterrestrial master.”

Martin Schmidt and Drew Daniel in unison: I am an extraterrestrial master.

Drew Daniel: (humming).

Martin Schmidt: I am an extraterrestrial master.

Drew Daniel: They just say “I’m an extraterrestrial master” and hold tones. (humming). Different male and female voices say that phrase, and it’s like 45 minutes of that.

That’s incredible.

Drew Daniel: We just love it so much that we knew we had to cover the tape. So we were in this castle in Italy, we got this crazy windfall arts residency at this castle called Civitella, and this composer, who writes operatic compositions and new music, Kate Soper, was there too. We convinced her to go with Martin into this cistern.

Martin: Yeah, it was a place I discovered.

Drew Daniel: We were dicking around in the castle.

Martin Schmidt: So I’m in this hallway, and there’s a drywall wedge shoved into a door shape, and I was like, “Okay, cool. What’s in there? Maybe It’s a bunch of cans of paint.” But sure enough, it was a corridor that goes back. So I use my phone flashlight because there’s no light, and I’m looking around, and my foot touches the edge of a drop-off. Then I looked up and I found this fucking cavern, which was this cistern and water supply for the castle from the 1400s. I had almost fallen over. It had a gorgeous reverb.

Drew Daniel: So we recorded Martin and Kate singing, “I am an extraterrestrial master,” there.

Martin: She asked what should she sing and we—

Drew Daniel: Just say that you’re an extraterrestrial master. From there we started to collect sounds of other people saying it. There’s Max Tundra and Vicki Bennett and Sam Salem and Wobbly, just a shit ton of people all saying it.

Drew Daniel

I did appreciate the comedic elements of the record. I’m a big fan of experimental musicians who aren’t afraid to dabble in humor. I was listening to the record and almost did a spit-take when I heard the Netflix intro sound play on side three. I didn’t expect it at all.

Drew Daniel: (laughs). I think that “dun-duh” is like the Pavlovian bell informing you that you’re about to be pleased and entertained. It might also be that it’s the gong of failure because you didn’t think of anything cooler to do with your life, so here you are pressing the content button as hard as you can. So we just thought, what if we kept playing the sound, but nothing started. I hope they don’t sue us. They have much more money than we do.

I don’t think they will, and if they do, well maybe it’ll give you some more press.

Drew Daniel: Okay good (laughs). Well, I’m glad you spotted that. We faded in the white noise introduction from HBO right before it. And Hulu tried to have some distinctive audio stabs (sings the Hulu startup jingle), so that’s in there, but I feel like it’s not as iconic as the other two.

I forgot about it until you mentioned it, but I did enjoy the HBO fade-in being used. At first I thought it was just the beginning of white noise or an ambient section.

Drew Daniel: There’s a funny story surrounding that and the voices speaking during that section. Martin made this cocktail jazz in Italy, and he asked Porest, who makes funny, political cut-up music—

Martin Schmidt: Wait, wait, so one of the ideas for this record, and it was one of the things I said to the 99 contributors to make whatever they want, but if there’s a tempo or, I’d also like them to make something using synthetic speech. Well, almost no one did the synthetic speech thing, so that ended up not being as much of a focus as we thought.

Drew Daniel: So we asked [Porest] to make a virtual cocktail party of chit-chat, that would be the background to the cocktail jazz music because his music often features this text-to-speech work.

Martin Schmidt: Do you mind me asking if you know his stuff?

I’m not familiar.

Drew Daniel: Oh, seek it out. It’s really great.

Martin Schmidt: He’s quite an interesting artist.

Drew Daniel: He compiled the I Remember Syria album for Sublime Frequencies, and also toured with Omar Souleyman and translated and represented him.

Martin Schmidt: And he’s in Negativland.

Drew Daniel: A lot of what he does involves button-pushing around the West’s representations of the Middle East, liberal democracy’s delusions of its openness and freedom. There’s also a lot of third rail collages about 9/11. Anyway, he wrote this cocktail chit-chat that’s supposed to sound like California tech workers having conversations.

Martin Schmidt: I wanted him to make a wall of chit-chat for us. He told us to just collage it ourselves and gave us 24 three-minute conversations. It must be that one of his side hobbies is collecting these digital voices.

Drew Daniel: So we were supposed to have this area with all this chit-chat happening as a cloud, and you can’t make out what’s being said, but we decided to violate some of our own terms and just let some of these voices be heard—

Martin Schmidt: Because they’re just so good.

Drew Daniel: But we didn’t write them. It was all him. So, it’s like these voices saying things like, “We met on Tinder, we died soon after.” That’s all him. You know, it’s weird to talk about this album in some way because it feels like we’re taking credit for what other people did. Like John Elliot made some amazing synth lines, Giant Swan made some sick techno, and then some people gave us something cool, and we heavily manipulated it and mediated it to the point where they might not recognize it. Like François Bonnet, who does stuff as Kassel Jaeger, we heavily processed his work.

Martin Schmidt: It was a perfectly good contribution, though.

Drew Daniel: It’s hard to know at the individual sections what the mix needed, and that led to some pretty heavy transformations. Like Blake Harrison from Pig Destroyer gave us a harsh wall of noise, and I’d strip the frequencies and use a slice of the mid-range to create a buzzing sound. There’s also a lot of field recordings that we used as a sort of glue to get the listener from space to another. And I made many of those field recordings, and Martin collaged them. So he used recordings that I made in China and Uzbekistan, but there’s also a lot of Baltimore, Japan, Minsk.

I wanted to steer back to the length of the recording for a moment. I’m sure that putting 99 collaborations together will make up a ton of time, but how did you end up at three hours?

Martin Schmidt: (holds up a rough, cut up, glued chart with collaboration sections and time stamps on it).

Perfect.

Martin Schmidt: We had made smaller units. I’d start with somebody’s contribution and then think of something that would go well with it, and we’d end up with these clouds. Not on purpose, but they’d end up as song lengths, and we’d put them all together.

Drew Daniel: Yeah, it wasn’t initially planned as three hour-long movements. What happened was that we had so much material, and [we threw] away some stuff that just wasn’t strong enough.

Martin Schmidt: But we still felt honor-bound to include 99 artists.

Drew Daniel: We had to let 99 people in, but once you’ve got “x” minutes of raw material, then you’ve got to think about which mediums are the most user-friendly to experience this album with. That’s when we decided that it shouldn’t be vinyl. That’s wasteful, and it’s interrupting because every 20 minutes you’re turning the record, and that’s not the flow state we want the listener to be in. Then we thought that it could be a purely digital thing. It could be one file, but I thought that doing that didn’t give people a chance to go pee or have a coffee. And I think, in the end, it was just a compromise between Martin and Thrill Jockey.

Martin Schmidt: Yeah, it’s just problem-solving. You know, for many years, we’ve said that we don’t really do experimental music. Really, very few people do, like where people say, “OK, here’s what we’re going to do, and whether it’s good or bad or interesting or not, here are the results.”

Drew Daniel: Yeah, the pure black box is not what we do. We’re conceptual, not experimental, maybe? I don’t know.

Martin Schmidt: In this case, maybe it’s more experimental than most of what we do, in that we had the parameters of including all 99 people.

Drew Daniel: And that the tempo was going to be constant. The tempo isn’t supposed to be a monotonous, exhausted, foregrounded element. It flows.

Martin Schmidt: Part of the fun was that it was all made at 99 BPM but you often forget that at times because 198 and 49.5 were fair too.

Drew Daniel: Also, having moments of hemiola or a swung thing help. There are tricks you can play on the ear that impact the listener’s awareness of what the grid is doing. It can feel like it’s breathing. It’s just that it can’t speed up or slow down. Also, knowing that we had the three-CD [format] was very helpful because it let us listen to it all again and go, “What are the three strongest opening moments? What are the three strongest landings?” That allowed us to create three narratives out of material that was always designed as a sort of center that had a loose on-ramp and loose off-ramp. But it was hard to layer this whole record because there’s so much material and finding out what’s the best way to do this without making the thing too long that still feels eventful but doesn’t get annoying. I don’t like it when music is worried that you’re going to be bored.

Absolutely. I agree.

Drew Daniel: I don’t like that, and I fall for that sometimes. I thin Martin is better at letting things breathe, which is why he did more of the assemblage of the record than I did. [He] did a lot more of the architecture of the crossfades and the handshakes between elements. I did more rhythmic programming of the denser moments on the record.

Martin Schmidt with students at the San Francisco Art Institute

Going back to that idea of experimental music, you both dedicated the album to the San Francisco Art Institute, and Martin mentioned in the press release that there are former students on the record. How did it feel having former students on a Matmos record?

Martin Schmidt: Great! I kind of look at everyone in the world as material to work with (laughs).

Drew Daniel: Capitalist resource extraction!

Martin Schmidt: The capital part is the part I fail at, though. So, I worked at the Art Institute for 15 years and taught for some of that time. I was mostly just staff for that time. I also taught during the school’s final semester.

Was that this past semester?

Martin Schmidt: Yes, it started in January. The class—and I taught it a couple of other times about 10 years ago—was called “Sound as Music.” I basically just did whatever I wanted to. During this [semester], there was a lot of concern about computers. I think one of the great tragedies of really contemporary—as in right now—music is that the activity of music has become a lonely thing where you sit in front of your laptop just like everything else you do.

So I was like, we’re going to sing, and we’re going to clap and build instruments. We’re going to do everything that is making music that isn’t the software. Because honestly, my feeling about software now is that it’s so easy to learn, unless you’re going to become a mastering engineer or something extremely technical, you don’t need to take a class in Garageband. [The school] insisted that I do it, though, so I was like, here’s how you put a sound file into it. By the end of the day, they knew how to construct a song or whatever. So at the end of the class, I had plenty of singing and clapping recordings, and that’s where [the students] are featured.

Drew Daniel: I visited Martin when he was teaching on the intensive when the students were playing the instruments that they built, and I just went around with my laptop mic and recorded little snapshots of each instrument and the students learning how to record themselves. Then I recorded Martin teaching them how to record. So the track called “Adepts,” is the one that features SFAI students and Martin teaching them about how to position the microphones. There’s a moment when all the music breaks down, and Martin goes, “The sound comes out here and into this hole.” So there’s this moment of pedagogy happening, and I flagged that moment just because there are some in-jokes about the Art Institute and this record.

One is that in 2006, Martin and I co-taught a class called “Theory and Practice.” I was fresh out of grad school and didn’t have my current position, which is at Johns Hopkins. And in that period he did “Technical Tuesday” and I did “Theory Thursday.” Anyway, one of my students was this incredibly bright kid named Nate Boyce, who was always telling me about critical theorists, amazing gear, and he’s now a sculptor and video artist who is quite well known. He also plays in the touring ensemble for Oneohtrix Point Never, but he has a duo with Eli Keszler called Pedagogy. So SFAI’s links to Matmos are here not just in a class from this year, but people who were our students 14 years ago and have become acclaimed artists themselves.

I’m not trying to take credit for Nate Boyce or anything, I think I learned more from him than he learned from me. But he was also in Matmos for a tour we did with Zeena Parkins. So it’s interesting to have Oneohtrix Point Never on our record, but so is Nate, and Nate is somebody that we’ve known through various points in our lives. When you’re old, you can look back, and you have these sedimented decades of your past. That’s one of the fun things about not dying.

Since you spent so much time at SFAI, it must be hard that the school has closed.

Martin Schmidt: Yeah, it’s a tragedy. I didn’t even realize how great a school it was until I left. I got the job there because I bootlegged a bunch of software in the ’90s and learned how to use Photoshop and Illustrator and FreeHand. It was early enough where they were like, “So you know computers?” It was that long ago. So I became a computer expert at this school because their technology moved slowly. After all, it’s a school that was primarily about the ideas and not about the technology. Specifically, the department I was a part of, the New Genres Department, their feeling was that they didn’t care about how you got your ideas across, they cared about what your ideas were.

So they had video equipment, but I was so angry, as a tech nerd, at this idea that people were expected to learn how to do a thing without the teachers teaching them because the teachers were only talking about why they did what they did and what their ideas were in the first place. I was like, this is all ass-backward. They should learn how to use a video camera and edit. After about 5 years there, I realized that I was completely wrong. It is better to come at things conceptually because the content of what you do is more important than the form.

Drew Daniel: You can make a lot of slick, soulless art if you focus on the “how.”

Martin Schmidt: My example was always, do you want to see a TV show where everything is perfect, everything is in focus, the sound is perfect—it’s called Three’s Company. That joke was funnier when people watched that show. But there you go, there’s a completely hollow piece of trash that looks fine, all the professionals are in place. We’ve got professional joke writers and camera people, and it’s all garbage.

Unfortunately, that same mistake I made [when I first got to SFAI], is what drives most art schools now. They’re all about having the best computers and cameras and printers while faculty don’t matter. All they need to know is how to use technology. What we get is a bunch of people who are good at making advertisements. And it takes very few clever people to make advertisements, so the really smart ones, who are smart, write clever ads, which is why we’re in the world we’re in now, where more frequently the ads on TV are more funny, surreal and interesting than the stuff in the show. It’s a tragedy of the United States of America. So, of course, the school closed. Who would want to go there? They don’t have the X-5000. Go to the school that has the X-5000.

Drew Daniel: It’s a parting of the waves between a truly radical, conceptually-oriented fine arts or bust model versus a school that understands that parents want their money to be turned into jobs that provide stability. So, it’s about, do you pick an institution based on where the money comes from and what’s the value for money in the eyes of the person who is paying versus another way of thinking about it, which is, here’s a group of radical experimenters who are going to press you about the poetics of every decision you make about why your work is doing what it’s doing, what is it about, what’s behind the choices. A place where you’re going to get pressed hard by smart people versus a place where you’re going to walk away with skills. I don’t want to spit on people’s anxiety about finding a job, like shit, COVID has exposed that making rent is hardly a given for most people. It’s just sad though that the Art Institute is gone. For me, it was a place that was inspiring, and that gave Martin and me a platform in which to perform and talk to smart people about their art. So there is a certain mourning for the loss of the school.

[The closing of the school] went down as we were finishing the record. We didn’t think about it when we were making this music. It’s more that something grandiose and maybe unrealistic and fun reminded us of the Art Institute.

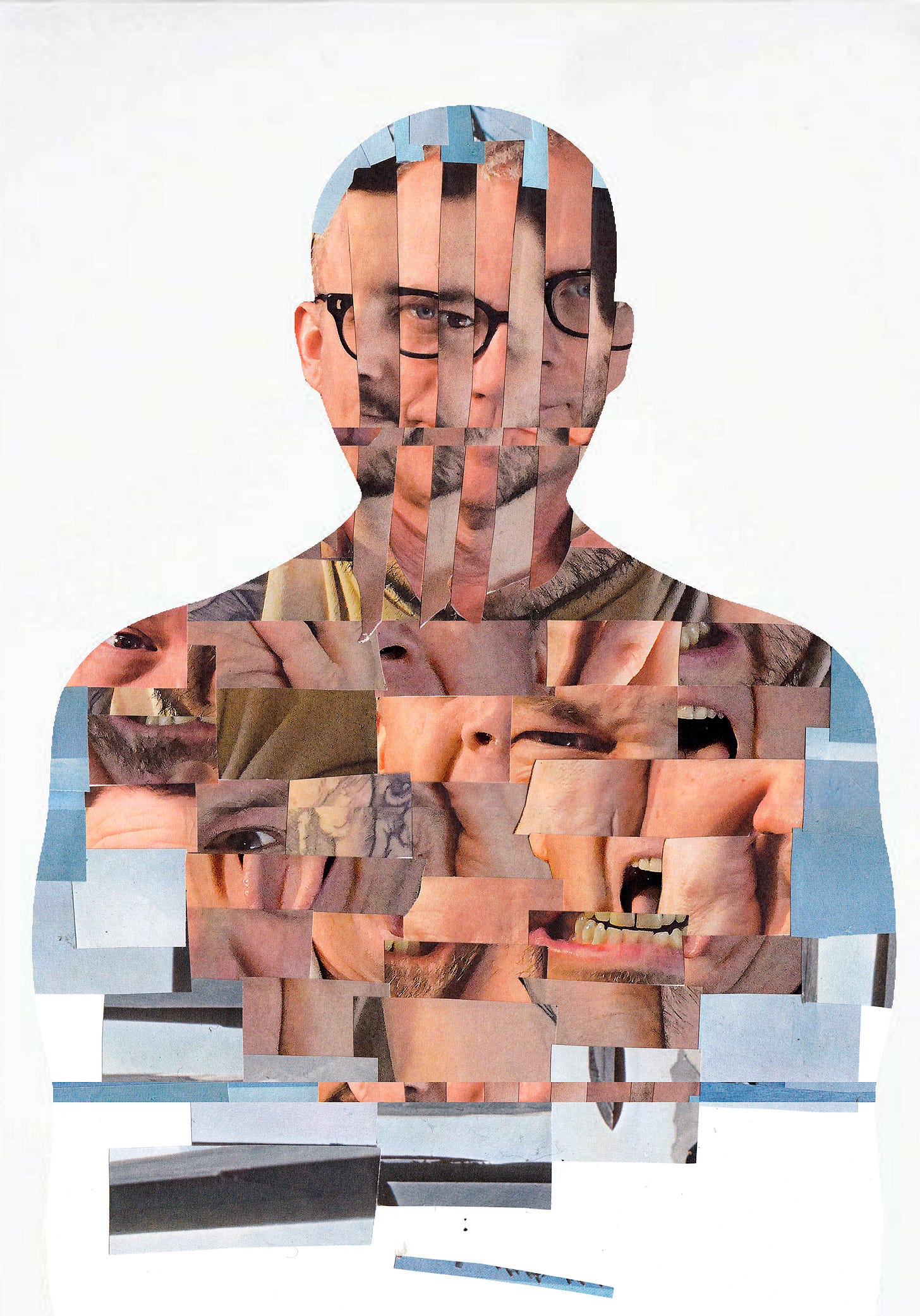

Martin Schmidt playing a flute while wearing a fur coat because it was cold in their basement

It gives a little more weight to the fact that students are on the record now that the school is closed.

Drew Daniel: Yeah. I think that question of, who is a professional? Or, who is an amateur? I want to keep that open. I don’t want to make polished bullet-proof art, and getting the perspective of somebody whose relation to sound is different than yours is helpful. We have a friend who is amazing with a very simple app called Sampletoy, which he manipulates and holds the cellphone in his mouth. So he folds the phone into his mouth and manipulates the parameters with his fingers.

Martin Schmidt: He plays it like a flute.

Drew Daniel: So that’s David Serotte, and he gets a kind of solo moment on disc three. It sounds like throat singing.

Martin Schmidt: He’s using a Chinese scale, so it’s kind of “Chinese-y,” for lack of a better word.

Drew Daniel: It’s like minute seven of disc three. It’s hard to keep track of this whole thing, and we were the ones who made it. I mean, sort of.

As the record is released do you feel like any extra pressure, then, since there’s so much material that’s not yours?

Drew Daniel: Yes, and I want to stress that it’s more like a mixtape and less like an album in the sense that it’s this sort of plural congeries of our friends coming together rather than something Martin and I masterminded. It’s less deliberate and more open.

Martin Schmidt: We were more of the administrators of this, rather than the creators. I mean, we administered the hell out of it. Of course, it makes me very nervous. It’s asking too much. It’s insane, and I really appreciate that you even listened to the entire thing, and thinking about the entire thing is fucking exhausting.

Drew Daniel: I hope it’s like a party where there are three different floors, and you can wander in and out, and it’s a little different each time. Maybe you stare into an ashtray, or maybe you get into a great conversation, or maybe you slip on some vomit. You know, like a lot of different elements are there.

Martin Schmidt: (Looks at Drew with skepticism) Sure, I guess. Maybe. What?

To that point, though, in my opinion, it doesn’t feel as exhausting because of that 99 bpm parameter. In the press info, Martin alluded to it as a train, and I felt like that captured it well. I felt like I was on a train, driving past these weird little villages.

Martin Schmidt: Cool!

Drew Daniel: Yeah, that’s our goal. I think it is something that meanders and is variable in respect to how attention-seeking it is.

Martin Schmidt: It’s pretty attention-seeking. It’s pretty hard for us [to make something that isn’t attention seeking]. Drew just made a very nice record that everybody likes that’s pretty ambient, but man, that is an uphill climb for us. A calm plateau is not where we reside.

Drew Daniel: I just think life is cluttered. Reality is cluttered. Look at the room we’re in. We’re not in some minimalist white room. There’s shit everywhere, that’s life.

Martin Schmidt: That’s our life.

Drew Daniel: I think some people want art that’s like a chapel, and there’s an appeal to making records that are like a chapel, and maybe my The Soft Pink Truth solo record was more like a chapel. This record is more like a train station or flea market, where there’s all these tables filled with chachkies that are saturated in different histories. Maybe you pick up somebody’s toothbrush, or their necklace or sweater. There’s just more going on. I hope it doesn’t come off as arrogant. I guess that’s my fear. I don’t want it to be perceived as this pompous assumption that everyone is going to drop what they’re doing and give me three hours. On the other hand, given our lives in quarantine and how people binge podcasts—

Martin Schmidt: What else are you doing?

You might as well listen to the new Matmos.

Drew Daniel: Right.

Martin Schmidt: Although that was never a plan. We were done with this before it all started.

Drew Daniel: Yeah, it’s all voluntary. We’re not twisting anybody’s arm here.

Martin Schmidt: It’s a bargain! Three hours of music for $13. Other’s talk. Here, we deal.

There you go, it really is like a flea market.

Martin Schmidt: Yeah, that’s a good metaphor.

Drew Daniel: Well thank you. Maybe it’s better than the party one. Oh, do you have questions? It’s been over an hour. We don’t want to exhaust you.

Truthfully, we hit on nearly every question I wanted to talk about.

Drew Daniel: (laughs). What is Matmos like?

Martin Schmidt: They never stop.

Drew Daniel: Annoying (laughs).

No, you two have been incredibly easy to talk to.

Martin Schmidt: I can’t even fucking believe—you know, people make me cringe. I swear to god, every time I talk to someone, another musician, I’m like, “Really?” They always say, “I hate interviews,” and I’m like, “Really? We can’t wait for interviews!”

Drew Daniel: People are so afraid of being somehow consumed by being known. Or that, I guess, maybe this is a little uncharitable, for some people I think that their brand is mystery. So disclosure is like a betrayal of their own special unicorn-ness. I just don’t think that’s how subjectivity works. I don’t think that ourselves are like sponges, where you squeeze the water out through talking.

I can understand from the artists’ point of view, too. Being asked the same questions over and over would be tiring.

Drew Daniel: Yeah, I mean if it’s a divorce album and you’re a songwriter who’s singing about your spouse then it is alienating to jump through hoops where you turn complex, interpersonal shit into an interview soundbite. But see, because my husband is right [next to me], and we made the music together, and we haven’t divorced, there’s just no anxiety. There’s only anxiety about saying dumb shit.

Martin Schmidt: I think people who listen to music, and I’m going to go out on a limb here and say boys, want the blankness. Look, I love Autechre, and there is an appeal to all the lights being out, you can’t see them, it’s really loud. It just obliterates all the little things you think about. I think a lot of people seek that from music. You know, “I just don’t want to think about anything!” (makes explosion noises with his mouth). “I just want to be a powerful viking in a fantasy world or a giant robot that can destroy all my problems!”

Drew Daniel: But Autechre isn’t a power fantasy, it’s a cerebral exercise in formalism.

Martin Schmidt: Sure, yeah. But the darkness! And they do interviews now and are very personable, super smart, sweet guys, but for many years, they didn’t do interviews.

Drew Daniel: Yeah. It works for some people. It’s just not our style. Part of it is that, to me at least, the music is not exhausted by the recipe of how it was created. I think that’s one of the mistakes about our work is that people think, “Oh, that’s the washing machine album, so it’s about the fact that it’s made out of a washing machine.” Yeah, that’s where it starts, but that doesn’t determine how it could make you feel or what it could be used for, or where it could take you when you receive it.

Martin Schmidt: I mean, I had that stupid washing machine idea literally because it was so stupid, maybe we could talk about music. We spent a year and half talking about washing machines, which was fine, and fun, and silly.

Drew Daniel: In this case, It’s another solution to the problem of how to avoid the trap of self-expression. If it’s 99 people, it’s not about my issues, or Martin’s issues. It’s not impersonal, because it’s filled with personality, but it’s another solution, which is like too many personalities. There’s just too many people talking, and there’s even a moment where one of the computerized voices say, “Every time I try to speak, you say something stupid,” and it’s interrupted by another voice. I think that’s more like the way we love now. It’s overload.

Martin Schmidt: But I certainly understand and empathize with people who want the opposite of that. Every time we make a record, I say to Drew at some point, “Maybe we should not do interviews.”

Drew Daniel: Yeah, or just not tell anyone what something is made of.

Martin Schmidt: Maybe we should make another record and shut up.

Still from The Washing Machine (Ruggero Deodato, 1993)

Thank you for reading our special midweek issue of Tone Glow. Please don’t make Matmos cringe.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.