Tone Glow 026: Derek Baron

An interview with Derek Baron and an accompanying mix + album downloads and our writers panel on Ellen Fullman & Theresa Wong's 'Harbors' and Matmos's 'The Consuming Flame'

Derek Baron

Derek Baron is a writer and musician from Chicago who currently lives in New York. They have released music both solo and in groups such as Cop Tears and Permanent Six Flags. Baron’s most recent solo album, Curtain, is out on Recital and features chamber music, field recordings, and diaristic sound collages that feel at once homey and sacred. Joshua Minsoo Kim and Derek Baron spoke on the phone on August 7th, 2020 to discuss art that is “permission-granting,” the notion of sacredness, living a life of research, and David Wojnarowicz. All photos by Emily Martin.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Hello!

Derek Baron: Hey!

How are you doing?

I’m doing good, how are you?

It was Bandcamp Day today, and with every Bandcamp Day I spend like three to four hours making a Twitter thread of things people should hear. I did that and then got some other work done and now I’m here.

When your phone call came in, it said it was from Des Plaines, Illinois. I’m from Chicago—Oak Park—and whenever I get spam calls now they’re always numbers that are really close to my own number. It told me it was a “Spam Risk” call just now, but I’m really glad that it wasn’t (laughter).

It’s a little hard to hear you right now, I just wanna make sure that this conversation is going to work.

I’m outside and I was gonna be in this nice, quiet spot but it rained so I’m on my way back to my apartment.

How far away is your apartment?

It’s like thirty minutes away.

I just found out about your album a couple days ago, and it makes a ton of sense that it’s on Recital both with what your music sounds like and the aesthetic that the label strives for on a visual level. I wanted to ask you about one of the writing prompts that are listed inside the booklet for the album. It asks you to “Remember a recent dream or memorable/recurring dream.” Can you do that for me right now?

That’s really interesting, do you have the booklet right now already?

No, there’s just a photo of it already on the Bandcamp page.

[the sound of rain obscuring Baron’s voice]

Oh wait, hold on. I can’t hear what you’re saying, the rain and the sound of cars passing by is louder than your own voice right now.

Oh no! I’m looking for the quietest possible route home but in New York it’s kind of hard to find that.

Would you be able to talk a little bit later? When’s the latest you could do an interview?

Whenever, really. I usually go to sleep around 1 or 2, so if you wanna call any time that would work.

Okay cool, let’s do that. Let’s do 8:30 my time, 9:30 your time.

That’s good. Sorry about the sound!

You have no control over that, it’s all good.

(laughs). Yeah, totally. Just give me a ring whenever you’re around!

Sweet, I’ll send you a text right before I call too.

Sounds great.

[hours pass]

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Hey, hey! How are you?

Derek Baron: Hey, I’m good, how are you?

Just ate some food and now I’m here. You doing okay?

Yeah, I had some food too. I ran home in the rain and then I was just kind of sitting around doing… not much!

Let’s start off with the question I was asking earlier. In the booklet to Curtain, there’s a collage of different images and texts. One of the things included is a writing prompt about a recent or memorable dream that you’ve had. Do you have one you can share?

When you asked it before, I was trying to remember the situation that led to that question being included in the collage. It’s funny that that’s coming up now because last night I had this dream where somebody was talking to me about the history of the English language and was talking about—and I don’t know if this is gonna make any sense because this is the first I’ve thought about it since this morning—how the English language has evolved and there are all these political implications for why we use the words that we use. And that’s totally true and everything.

He was like, the reason we use certain grammar is because of the government controlling the language and whatever. And he was like, “Take an example, that’s why sports commentators are the most creative speakers of the language because they can say whatever they want.” He was imitating an announcer for a dog race and started talking, like, you know those auction criers who talk really fast and speak their own language? He started talking like that but narrated this fake greyhound dog race to me and I was really, really taken aback. I woke up and started to turn on a sports channel (laughter).

Wait, this was all in a dream?

This was all in a dream last night, yeah.

Oh wow. Do you think there’s truth to sports commentators being freer than most people with the way in which they approach language?

You know, I wouldn’t think that sports commentators are at the top of the list. I would think poets or something like that (laughter) but, I don’t know, I guess there’s only a difference in degree between a really passionate sports commentator and a poet, so I’m down for the baseball commentator to be up there with the real avant-garde leaders of the English language.

When you’re a sports commentator you have to be familiar with this specific language—you’re confined to the way in which you can speak in that there are certain rules and expectations there, and dynamics employed.

Yeah, within the confines of the lingo of the sport, you can make really interesting terms up to describe different things that people would intuitively understand because it’s such a perfect phrase for something. I wouldn’t be able to do that because I don’t know the ins and outs of the language, but if you live inside that, you can really do something with that.

This is a total aside, but there’s not a lot of music I think about that’s related to sports. The things that come to mind right now don’t really have to deal with language though… there's the Taku Unami & Éric La Casa collaboration Parazoan Mapping, if I recall correctly there are a few tracks where there’s a tennis match and a basketball game that they record. But they’re like chopping it up and magnifying the different sounds that are present. And then also there’s that album on Every Contact Leaves a Trace.

The golf one?

Yeah! The Masters. I love that one.

It’s amazing. Is that Henry who did that?

Yeah, Henry Collins. It’s a hilarious album.

Isn’t there the Devin [Disanto] and Nick [Hoffmann] album that’s recorded in like a high school gym?

Yeah, that’s Three Exercises. I think they use golf balls, or ping pong balls.

Yeah, ping pong balls.

Weren’t they using a bingo cage at one point on that? I haven’t heard it in a while. I wrote a review of it back in the day.

I love that one. I love Devin’s whole “office ambiance” sort of sound palette. Staplers and stuff.

I was talking about this recently with someone about how sound sources can be familiar—we know what a ping pong ball bouncing around might sound like—but an ambiguity can still be present such that you’re wanting to figure out what’s happening. Devin Disanto really knows how to find that balance. I like how you said “office ambiance” because I never really thought of it like that. I always think of his music as him conducting very procedural exercises. There's transparency there because specific steps are being taken, but because there’s no visual component it’s automatically rendered acousmatic.

Right, right. I’m even just thinking… I saw a show of his in New York that Jon Abbey [of Erstwhile Records]. It’s really procedural but there’s a different kind of procedural than what you get with a Marginal Consort show where the procedure is absurd or surrealist in a way. To me, Devin’s procedures—and there are others who work sort of like this—it looks like it sort of makes sense because there are objects you understand: a stapler, a projector, a stack of paper, a roll of duct tape. But nothing really adds up so that really sparks my imagination.

This is interesting to me. Obviously your music and Devin’s music are very different, and a lot of your work is sound collage stuff, though I’m reminded of this “midpoint” that’s found. There’s field recordings mixed with chamber music on your albums and when I think about your music, there’s always a domestic and familiar and intimate atmosphere, but there’s also a peculiarity present due to how it all comes together. What makes you approach music in this manner? What appeals to you about it, and how do you approach any piece that you make?

It’s interesting to compare it to that sort of procedural thing because I feel recently, in the last couple of years, I’m much more zoomed out in a way from the images that I’m putting together. A lot of the stuff that I’m working with was recorded from really far away. It’s similar to a Shots thing, almost, where there’s a certain flatness of the canvas. Maybe Shots is somewhere in the middle. I talk with a lot of people who are working in this vein but recently I was having a conversation with Matthew Sullivan and there’s something really similar in a lot of his recent work.

Oh yeah, for sure.

There’s distance and things are put on this really wide canvas, is how I see it. Where they’re domestic sounds or musical things coming up or field recordings from outside or whatever, to me it’s a marked difference because my first handful of records I would try to do a little more of the up-in-your-ear or grating—and not necessarily noisy—style, the close-mic’d and lowercase thing.

I remember on Palmillas, I think, there are certain sounds that are clipping because they’re so closely recorded.

Yeah, totally. I still listen to a lot of music that’s like that but the way I’m approaching things now is much more zoomed out.

I love this. When I listen to a lot of Matthew Sullivan’s works, it feels like I’m peering into someone’s space. It’s not like I’m directly next to them but maybe that I’m down the hall or just there in spirit, but more tangibly so or something. The zoomed out aspect of your music makes sense because each part in any given composition has their own distinct presence and every element can be appreciated for what it is and for what it’s contributing to the whole.

I was thinking today that with the second side of Curtain, which is more of the collage-y type of thing, and with this piece i did for ISSUE [Project Room] in May, these are two examples of me trying to experiment with letting things be what they are. This is instead of doing these microscopic edits where I have these perfect little seams and these five-second clips of ten thousand different field recordings. It was about letting things go, about letting a seam just happen for a few minutes.

The musical time of a 20-minute side invites a little bit more impatience for me. I may be like, “Oh, I’ve got to get so much more in” but I’m learning it’s okay to let things go and to go inside of a moment. I feel like I knew that when I was younger, or when I started to be really taken with field recording music or different kinds of non-music things but I had forgotten it. I’m letting things be just a little bit more.

Do you feel like there’s any particular reason why you’re in this zone now? Where you don’t feel like you constantly need to stimulate the listener or have a bunch of stuff going on?

I feel like at least one thing that’s changed with my approach in the five or six years is that for the past three years, I’ve been really busy in school. That’s fine and nice and everything but before that, I was doing music pretty much full time and working at a bar, so I was spending the vast majority of my time doing music and thinking about music. Recently, I have this day job so I don’t necessarily spend 40 hours a week digging into a record or making a record. I don’t want to say that music is my hobby now even though that’s fine and it’s true, but I want something different from it. I don’t want to be assaulted by it. It’s doing a different thing to me psychically or therapeutically now that the shape of my life has changed so much. It makes me realize, also, that everyone comes to the music that they’re interested in based on how it works for them. It’s so obvious, but my relationship with the music that I love is so idiosyncratic to my routine and the time I carve out for it. That must be true in general, and it’s cool.

You never know what people are gonna fucking think about what you make, you know? I used to obsess about that a little bit more, I was a little bit of a perfectionist because I wanted the message to land on the other side, but now I’m just like, I’m gonna make the message land for myself and people are gonna have their own message if they check it out no matter what. I’m a lot happier now.

What are the messages that you want relayed through your music?

That’s a good question.

I guess not necessarily messages per se, but what do you want people to take away?

The things have been really eye-opening or exciting or permission-granting, at least in terms of the music that I love or have loved in the past, are things that shake the frame just enough that I realize that anything is possible. I don’t necessarily mean to say that that’s what I want people to get from my music, but I’m thinking of how deeply moved and disturbed I have been in hearing music that’s changed my shit. It’s this weird sense of bearing witness to somebody doing whatever the fuck they want and letting people in on that process for them.

A great example of this, obviously, would be Gabi Losoncy’s music when I first started to hear it, which was a very long time ago now. It was just, like, “What you believe you want to do is worth doing” in terms of the music you want to make, and you should just do that. It’s a sacred feeling, and it doesn’t happen very much to me. I felt like I was able to work out a process to make sense of my life and it’s been such a gift I’ve been given by the music I’ve surrounded myself with in the past. That would be an extraordinary privilege to feel like everyone could have that sense when listening to my music. That’s how I’ve thought about it in the past, of just making people think about their shit.

When you make your own music, are you wanting to model the sacredness of music-making for others? For others to be encouraged?

It is partly that I want others to be encouraged to do their own thing, but it’s not so much music-making in particular—for me that’s just been the easiest form it takes for whatever reason. I saw this quote the other day and I think it was Anthony Braxton that said it, but I’m not actually positive. He was like, “There’s something that I’ve been interested in researching my whole life, and there’s not really a word for it, but music is the closest thing that I can say that describes what it is, so I guess we can call what I’m interested in as being music.”

Anthony Braxton is another huge inspiration for me, as different as our output might sounds like on the surface, but there’s something about that—it’s not really the music that’s the point, it’s about a life of research, it’s about giving yourself the gift of doing your project and making sense of such a cruel world, of putting your mind to what a meaningful world could look like. And that could take any number of forms—an infinite number of forms—but I feel like doing music or art is one very available form that I’ve appreciated.

How would you say you’re doing right now with regards to your own life? Do you find a lot of meaning in it?

It’s a wild time and it’s an intense period for so many people in so many ways. I’m in the midst of processing a bunch of shit that’s going on, as so many people in the world are. At the same time, it’s taking a considerable amount of mental capacity to get through the day sometimes. The strain is on the very surface level day-to-day but it’s also on a deeper level, like seeing all the ways in which the world is ending or the massive suffering and injustice.

Part of the point of what a lot of this madness is about is that it’s not necessarily new. One of the things that I’ve been really interested in, in terms of how people are interpreting the coronavirus pandemic in light of the racial justice uprising is that the coronavirus has made visible what we were not supposed to see—the way power works was supposed to remain hidden in certain ways.

I’m just thinking at my workplace recently how there’s an emergency lock box full of money that we can use to help people if they’re in emergency situations like this global pandemic. We’ve all assumed this lock box was something we could tap into if someone was in a medical emergency and needed some sort of help. Because the virus made it so people were in actual emergencies, we were like, “Cool, we’ll get some of this emergency money that’s set aside for us,” but we were told that it was empty, that there was no money in there. They were just telling us it was full of money so we would think we had a safety net.

That’s crazy.

Yeah, it’s like this new level of reality is being unveiled to people (laughs). That’s how it feels to be going through the world right now. It's a surreal and absolutely terrible and traumatizing moment, but there’s also such fascinating and joyful things that are emerging from it as well.

What’s something joyful that’s been occurring for you as a result of all this?

Part of what I’m seeing in this moment is that the story of persistence and liberation is not gonna be one of simply suffering. It’s on this insistence of the joy and radical possibility, and that’s the real foundation. I haven’t totally put this into words yet but there’s this beauty in the insistence of life’s beauty and that it’s worth defending. That is coming out so strongly and it’s so holy to bear witness to.

That makes a lot of sense. There’s a growing sentiment of embracing one’s imagination for what the world can actually be, we see that with abolitionist ideas gaining a more mainstream platform. And we’re seeing that because of what you’re saying right now, with the truths about the world and various power dynamics being laid bare.

Sometimes the popular response to these uprisings or these public, traumatic moments is to affirm the terribleness of the situation. Obviously that’s important and it’s an extremely hard-fought truth for more people to say that the whole nation is actually rooted in racism and anti-Blackness. There’s this other side, though, of this moment that’s appearing really powerfully to me, and it’s this insistence that it’s not just that.

It’s so easy to just be like, “Oh, all this is about is revealing suffering.” But it’s just as much, if not more, about revealing joy and possibility and the imagination of abolitionist frameworks like you’re mentioning. I’m so humbled by that every day.

It’s interesting to me that you’re using words like “sacred” and “holy.” Across your music, on The Dress of the Century you have “Down in the River to Pray” playing at one point, in your AMPLIFY 2020 piece you have a church organ playing, on “Chancel” from your new album, you have someone talking about going to church. What’s your relationship with spirituality and religion and why do these things show up in your work?

Yeah, that’s a really good question and I’m trying to ask myself the same thing right now. “Chancel” from the new record is interesting because after I had finished it, I realized that it was totally about these religious themes in certain ways. On the A-side, which is the piece with Ordinary Affects and called “Curtain,” there’s an extended section in the middle that’s an arrangement I did of a mass by Arvo Pärt. There’s a sacred music thing all over it. That’s my mom who’s talking about going to church when she was a kid on “Chancel.” We were driving around and listening to the radio and talking, and after that there’s a recording of a rabbinical incantation.

There’s something resonant about why those particular musical signifiers are coming up to me in such a strong way. It’s not necessarily a conscious intention to bring sacred music back to the avant-garde, or to bring the avant-garde back to sacred music (laughs) but I wasn’t raised religious in any way. I’m Jewish, Eastern European, and the piece that I did for the ISSUE Project Room thing I mentioned earlier was in some ways more deeply rooted in the Jewish mystical tradition, if not musically then thematically. Those themes just keep presenting themselves as things I want to throw into the mix.

I do consider the practice of making music, as well as the practice of imagining abolition, to be sacred. I don’t even know what organized religion considers what sacred means, but those practices feel really sacred to me. It’s probably underneath the surface to me as to why, but it’s a really good question.

Let’s answer this for yourself then: What does it mean to you for something to be sacred?

Hmm.

Do you consider your own music to be sacred?

Wow, great question. No, I don’t think so. Well, I don’t know. Recently, I’ve been learning about these traditions either in England in the 17th century—or in the early United States or in Europe at a similar time—of these religious groups that broke off from the religious organization of the normal society of the time and their political vision was totally bound up with the sacredness of their community, with their religious vision.

Even for me, a 21st century secular Jew who has no interest in practice in that normal way—and I don’t even really know what that would mean—there’s something that I’m learning where the inextricable link between the imagination of the world that you want and need and deserve… that’s like the sacredness in the everyday. These are the roots of radical anti-capitalist, radically egalitarian communal experiments that had to set themselves against the predatory powers of the property-owning classes and church leadership of the time. There’s something in that that really connects to me.

There’s Bach peppered throughout my work just because I’ve studied his music so much. I don’t think his music is necessarily radically anti-capitalist (laughter)—he was a cool guy and everything but I don’t think I’d go that far (laughter). But there’s something weird that’s sort of connected with that Lutheran tradition and these radical abolitionists. There’s Anabaptists and the Shakers. These are just connections that appear to me.

Rather than try to pin them down with my music and saying, “I’m doing sacred music in the tradition of so-and-so group from 400 years ago,” I’m just interested in putting those pieces next to each other and letting something arise from that.

So sacredness for you has to do with exhibiting this bold imagination for what the world can be. Do you want your music to be sacred?

I think what I really want, as much out of my music as with my life and everything that I do, is to do shit with my friends (laughs). What I want is the world to be a place where people can have all of their thoughts and ambitions and differences and ideas and desires and work all of it out by yourself and with your friends. So much of the evil force that the world exerts on people is a prevention of people from just being people. If my work, even in the most minimal possible way, can join the chorus of people wanting to hang out with their friends and make alternatives to environmental collapse and racial capitalism in the present—just to be in the world of people who want to think about how we’re going to get out of this shit alive, and together, and with dignity—then that’s way more than I could ever dream of.

And of course we’re taught and conditioned to not have to rely on each other.

That’s the trap that’s so easy to fall into. That’s part of the trap when a piece of music comes out that only has my name on it, which Curtain does. And that’s more so a matter of convention than anything else. Not only is all of that music, especially on the A-side, performed by other people, even the B-side… that’s just the sound of me going through the world. I want to highlight the aspect of that B-side, as well as all of my work in general, as being a collaboration with my mom as much as it is a solo project. I’m in awe of how people collaborating with others is more than just the sum of its parts, even if it’s just a conversation with my mom about how she had gone to church when she was a kid.

Part of why it’s so apparent to me, or why it sticks out in my mind so much is because my music-making practice can be lonely. My job can be quite lonely.

What do you do?

I’m in graduate school so I’m just in the writing phase of it. I teach a lot—I’ve taught the last two years but won’t be teaching this coming semester—but a lot of it is just me alone with my books and making music is sometimes me alone with my tapes and my recordings. I feel the urge towards collaboration in a particularly heightened way because of that.

I think that’s part of the impulse behind the label work too [with Reading Group]. It’s about having collaborations with people puts me in a slightly different position than I’m used to and it’s really satisfying to put people’s work into the world like that. It feels like a way of collaborating that I feel really tuned into in the past couple of years.

You run Reading Group with your partner Emily Martin. And Emily is a significant person in your life who makes you feel less lonely.

Definitely.

Can you talk about Emily—what do you love about her?

That’s a great question. It’s what we were talking about earlier with this permission-granting of believing you can and should do whatever the fuck it is you want to do with your work or art or output. In a very real way, I learned that from her. If I didn’t learn it from her then it’s just by observing how she works that I learned that that was possible.

Earlier we were talking about that and I mentioned my relationship with Gabi’s music and that’s totally true, but I think talking to Emily and observing her process over the past six or so years has been permission-granting in ways that I can’t totally calculate because I’m still in the world that she’s shown me.

Can you provide a specific example of how her actions or words or demeanor or anything allowed for this permission-granting for you to be who you want to be or for you to do what you want to do?

She’s mostly a writer, and she and I collaborate in the group Permanent Six Flags and we do the label together, but most of her private practice is writing words. It’s mostly just me seeing this unselfconscious and fearless commitment to the project at hand. The writing practice she’s been developing for her whole life opened up a space for possibility for me that this is less about music than about researching your life. I learned that from the six years of observing her practice and from long conversations about how our life research is going and developing. I’m curious what she’ll say when she reads that (laughter). She’s gonna be like, “What the fuck are you talking about?” (laughter). No, she probably won’t say that. Or I don’t know, she might.

So music is about this life research, does that mean understanding and knowing things about your own life?

Sometimes it’s me realizing things about myself that I only did so from doing music—that happens all the time. But it’s also about having some frame to catch a life of thinking as it changes. It’s not so much research in terms of looking for an answer, but almost just like refining whatever the question is, or giving yourself time to ask the questions. It’s about having time to reflect and spending time with other people’s reflections through their art and being in conversation with people in that way.

When you revisit your past works, do you see yourself and where you were at those points in your life, and do yourself as being less “refined” than who you are now?

That’s a good question. I haven’t gone back and listened to a lot of my old work in a very long time, but I kind of have a sense that if I did, I would… (pauses). What I try to avoid doing is going back to old albums of mine, things that are quasi-finished pieces, but one thing that I have been doing that actually feels like a fruitful process is that over the past 15 or so years, I’ve accumulated 100 or 120 hours of just recordings of me fucking around on various pianos either in Chicago or in New York.

I never studied piano and my relationship to it feels really idiosyncratic and personal, and one thing I’ve been doing specifically with that aspect of my archive is combing through it and listening for very, very short moments where something comes out that must’ve been an accident, a slip of my hand. As I’m listening back, my ear can catch things in 2020 that my hand was doing in 2010 that my ear in 2010 didn’t even know was happening.

There is a sense that I’ve been thinking about the same shit my entire life, which is true. But it’s really interesting to be going back and finding microscopic moments and finding these strange turns of phrase that give me pause. I feel like isolating those and pulling them out and it feels like a way of thinking about how my relationship with music has been throughout my entire life. That feels like a mode of musical research that’s folding back in on itself. It’s research about research in a way. That’s a particular kind of navel-gazing I feel I can spend the rest of my life doing and be perfectly happy.

I was just reading the most recent interview that you put out with Chris [David] and you were talking about your relationship with listening to and making music. I’m so interested in people who have such a personal and what seems like such an encyclopedic knowledge and relationship to music which I imagine you having. Do you think of what you do as research, in a way? What’s the sort of process whereby you proceed. There’s so much music in the world—how do you find your way through it?

Good question, hmm. There are two questions there so let me answer them one at time. There are personal reasons that I do all the music writing I do. Part of it is “for the culture” because of how homogenous the music writing industry is in terms of what gets covered. I feel like I know at least a decent amount about music, I have the ability and access to write for music publications, and it’s something I enjoy doing—it consequently feels imperative that I do these things. Part of it is about documentation because I often get sad about how much is not getting written about—there’s so much music that hasn’t been documented, even in our recent past, and there’s a chance that it’ll never be written about.

I don’t know if I consider a lot of what I do research. When I interview people, that’s first and foremost about me having a love for talking with people, about knowing people, about understanding an artist as a human. You can’t really know an artist from just their music. Well, you can in some sense. When I listen to Joni Mitchell’s music I feel like I know something about her and who she is, but there’s so much there that you don’t get that can only come from a conversation—and that’s also why I try to do Q&A interviews. And with that, there’s an enrichment of the artist’s music because all art is an overflow of one’s life and experiences and thoughts.

If I consider something to be research it’s only if I’m exploring a new genre or reading books or something. I suppose in my mind research has this connotation of seriousness, or maybe I don’t equate research with something that can be fun (laughter).

You’re not the only one.

There are elements of it, though, that are very clearly research, though. What was your other question again?

That’s really helpful. But also, like, how do you—

Oh, like how do I listen to everything that I do? Is that a question about how I listen to it all and process everything?

It’s a combination of that, but also about how you make your way through a world where there’s such an oversaturation of music. Or do you even think there’s a lot of music? There appears to be.

I mean, if you only think about the stuff that’s getting covered, it seems like an incredibly small world. It seems so small. If anyone’s only access to information about music was from these publications, they wouldn’t really think that there’s that much music coming out. But I guess I don’t feel overwhelmed about the amount of music that gets released. I suppose I’m content with the thing that I do care about and I make time for all these sectors of music that I like. And periodically there will be this whole new world of music that I didn’t know about prior, but that’ll just be another addition to everything that I want to spend time with moving forward.

Perhaps this is egotistical, but I’m very sure of myself in my first reaction to any piece of music, which is ultimately just me being at a point where I have identified what I like and can like. But with that, there’s also this thing I learned from a friend where if I hear something and think it’s bad, the first assumption I make—or want to make—is that I’m wrong. The goal is for me to broaden my perspectives such that I can appreciate it. It’s a way I’ve come to terms with the amount of music I listen to, it’s this idea that I want to appreciate any given thing as much as I can, as much as possible. And sometimes that’s just me appreciating it on an intellectual level or in context.

There are so many times where I’ve written about a song that I may not like, but I’ll like the act of writing about it because it forces me to think. And that in and of itself is a process that I find rewarding. I said that writing about music is about documentation, but it’s also about documentation of myself. I look at the writing I’ve done in the past and everything I’ve done captures me at that stage in my life, and it goes beyond just my tastes or whatever. A lot of times I feel the need to write about music because I know I’ll want to remember what I’m thinking about—and how I’m thinking about it—in the future.

That makes a lot of sense to me. What you’re describing feels like a description of what I mean by a “life of research.” Having documentation of the stuff that you’re thinking and coming into contact with as it’s happening. I get so much out of people doing that for themselves. I learn about people and the stuff that they’re thinking about and it’s super rewarding.

Thanks for asking me a question. I think that’s the first time in an interview where someone’s asked me a question and I’ve responded at length. It’s cool. Speaking of artists and getting into their world, one of the big releases on your label is the David Wojnarowicz triple LP, Cross Country. What specifically drew you to him and why did you wanna release those tapes?

That was a really fortuitous project because I was researching him, in a narrower sense of the word—I was actually at his archives in New York. I was checking out his writings and photography and found that he had this huge tape archive of these tape journals from throughout his life, mostly from the last 10 or 12 years of his life—it started in ’81 I think.

I came upon these three tapes that were bound together with this yellow masking tape and had “Cross Country” written on them. I had read essays of his in the past—Close to the Knives—and had read his biography and was really fascinated by him as a person and felt close to him. There was just something about discovering these tapes in the archive, I felt like my brain was on fire for the next week. I remember hearing the third of the three tapes and calling Emily and just sobbing for how moved I was with this story that was unfolding before me. It’s an amazing story, he’s an amazing person, and it’s extremely heartbreaking.

The last tape in this series is also the last tape he recorded, at least for a while, and has him being like, “I’m really lonely and shit’s really”—this is in like 1989, he’s just been diagnosed with AIDS, his best friend Peter Hujar has died, and he’s alone in Arizona. He finds this one beautiful perfect moment where he’s alone in the desert, basically, and has a moment to reflect on the perfect stillness of this scene he’s watching. There’s something about how those tapes were already laid out—I was deeply disturbed and moved by them when I first heard them, and sort of started pulling out some of the layers.

At the very same time, a writer named Lisa Darms was working on a book about his tape journals, so she and I talked a bunch. And then I talked a lot with Wojnarowicz’s last boyfriend [Tom Rauffenbart] before he died, and it ended up becoming this thing where I had this super deep connection with these tapes and felt really called to it. It happened really fast. When I was interested in his work initially, I didn’t even know he had this whole tape archive, and it was really like a punch to the gut to come into contact with that. His voice in the tape recorder really affected me.

The opportunity was there and Tom, who was the executor of his estate, signed off on it and I worked with some of the archivists and threw it together without any idea if people would notice it or be interested or be bothered to deal with it at all. I think that was the first LP we did on Reading Group too and it was this massive project where our living room was just filled with boxes of these LPs (laughter). To me it was, both creatively and historically, really meaningful and satisfying thing to be able to do. The story is so relevant and important to me, it touches me so personally, so I was really pleased that people found their way to it despite me being really bad at press stuff (laughter).

I’m really happy that the release is out in the world. I imagine most people who know about him don’t know about the tapes either, I mean I definitely didn’t for sure. And this is sort of what I was saying about doing interviews—there’s something humanizing about this release. Obviously you get a sense of who he is from his work, but maybe there’s just something about hearing a human voice.

Yeah, it really does something. Lisa’s book came out around the same time as the LPs and while there’s an extended introduction, it’s basically a transcription of everything he says on those tapes. It’s really awesome and an amazing resource to have, but there’s so much that’s going on that you can’t really transcribe. There’s ways that the pacing changes when he’s really getting fired up, and there are long moments of silences.

At the end of that moment I was describing, which is transcribed in Lisa’s book, the tape cuts out and when it cuts back in he’s at SeaWorld in San Diego and he’s not saying anything. He’s just in the bleachers watching the Shamu show and it’s just the sound of super intense Americana, of these whale trainers giving this show to all these families.

That runs for like 20 minutes at the end of the last tape and 18 months later he dies in New York and there’s just something about the movement from this amazing moment he has privately in the desert and then he’s at fucking SeaWorld and there’s no other speaking. It’s like, oh my God. There’s something about the format of him going around the country with a cassette tape recorder that made that scene possible, and I really wanted to transmit that.

Every medium has its pros and cons and I suppose if you can get to know someone through as many mediums as possible, then that’s the best thing to do.

Yeah, definitely.

Purchase Curtain at Bandcamp or the Recital website.

Tone Glow Mix

Every now and then, artists will provide a mix personally made for Tone Glow. Mixes will always be available for streaming and download.

Here’s a mix of some music and talking that I’ve been taken by recently and not so recently. There’s a lot of Chicago stuff, excerpts from talks and poetry, as well as some stuff I didn't realize I still had. In the Linebaugh excerpt, when he’s referring to the clown, Bottom, acting as the wall, he steps back from the podium and holds two fingers out like an open scissors just below his navel—that’s the hole in the wall that the lovers look through. The whole thing is on YouTube.

—Derek Baron

The tracklist for Derek Baron’s mix is as follows:

Town & Country - “Garden” from C’mon

Sue Tompkins - “Country Grammer” (excerpt)

Stefan Wolpe - Chamber 2

Eric Schmid - “+2122545428_20131014103158” from a channel, dedicated to Michael

Matthew Schneider - Track 01 from Roanne

Charles Ives - “Study No. 9 - the Anti-Abolitionist Riots”

Delia Derbyshire - “Land” (excerpt) from Dreams

Frank Rosaly - “Babies” from Cicada Music

Peter Roehr - “Morgens die Familie Versorgen

Liz Durette - “Angel Bell’s” from Delight

“Dialect Survey”

Waza trumpet ensemble - “Aba Musa ladoiya (1983)”

Erik Satie - Messe des Pauvres (excerpt)

Michael Jackson - “Don’t Stop Til You Get Enough” (Home Demo Recording 1978)

Olivia WB - Track 2 from Round Tuit

Norman H. Pritchard - “Gyre’s Galax”

Nouthong Phimvilayphone - “Khangdeuk”

Peter Linebaugh - “Magna Carta and the Commons” (excerpt)

Korea Undok Group - “Continent”

Fred Moten - “I Lay With Francis in the Margin”

Olivier Messiaen - “I: Regard du père” from Vingts Regards sur l’énfant Jesus

Four Thing - “6” from Four Thing

Download: FLAC | MP3

Stream: Vimeo

Download Corner

Every issue, Tone Glow provides download links to older, obscure albums that we believe deserve highlighting. Each download will be accompanied by a brief description of the album. Artists and labels can contact Tone Glow if you would like to see download links removed.

Danceries - Danceries (Denon, 1981)

Established in 1972 by conductor and multi-instrumentalist Ichiro Okamoto, Danceries was conceptualized as an ensemble that would play medieval and Renaissance-era music on period correct instruments. A group of skilled, classically trained Japanese musicians, they toured European venues and played medieval compositions with the goal of providing audiences a period-accurate experience. In 1974, according to Okamoto, the group was asked to incorporate some traditional Japanese music into their set while on a concert stop in France. The idea seemed antithetical to what Danceries was about and they were trepidatious at first, but they agreed. “To our surprise,” Okamoto recalls in the liner notes, “the European instruments imbued it with a rich, new color.” From that point on they would play a mix of European and Asian traditional music in all of their sets, and what Danceries was about became something new: providing a period-accurate experience sometimes, and providing the experience of Japanese musicians playing the part of European time travellers at others—in other words, being themselves.

This album—only their second, following a more strictly Renaissance-focused record in 1977—can be seen as the culmination of what they learned about themselves following that fateful tour of France. Foregoing the traditional wisdom of sequencing an album of period music by date of composition or grouping by their geographic provenance, they instead sequenced the tracks with the goal of creating “some kind of balance and bond between the pieces.” That’s significant, because it makes the difference between a museum exhibit and a creative endeavor. Not only did they include two Okinawan folk songs and one from Tsugaru (not played with a shamisen, notably, as music from the area is famously known for), they also had contemporary composer Yuji Takahashi create new pieces for them to perform with their instruments of choice in mind; the old and the new are presented together, with no divider to separate them.

Danceries would push this concept much further the very next year in a collaboration with the venerable Ryuichi Sakamoto called The End of Asia—a release that would see the ensemble performing stripped-down acoustic versions of sparkling electronic pop songs from Sakamoto’s Thousand Knives of Ryuichi Sakamoto alongside the early music that they became known for—but this 1981 record marked the first of only a handful of times they would commit this intersection of east, west, past and present to a recording. The two styles of music contained within this album inform one another: the Japanese music influences the European by way of the performers’ lived experience as Japanese people, and the European music in turn influences the Japanese as Danceries bring back home what they’ve learned from their journey through the ages; Okamoto says of the two that they are “so different and yet so similar.” —Shy Thompson

10LEC6 - Join Us! (Mollicut Records / Rock On Fiat Lux, 2005)

A few years ago I was flipping through records and found this chillingly rendered portrait of a child staring back at me. To be frank, the sleeve that houses Join Us! has been a major factor towards the staying power of this quick EP in my own collection. While the four songs are incisive and enjoyable, Jerome Zonder’s front and back cover art (included here in the download) surround the work loudly, sitting somewhere between work by Raymond Pettibon, Henry Darger, Heather Benjamin, and Junji Ito.

Eyes carved out and cells vibrating, the toothy child on the front only gives a hint towards the horror on back (cw for this paragraph and images in folder: body horror, sexuality, children). Scratched out between agitated text is a rapid-fire display of several baby-faced figures: toddler twins dressed like Men-in-Black, chuckling; a boy and girl cackling, feasting upon severed human limbs; a cybertronic child whose jaw has dropped so fully as to expose a small tower of circuitry and mechanisms; and two horrifically hypersexualized, cherubic figures, both with melon-sized tits and one with a visible and strangely non-anatomical cock. The entire layout is so filled to the brim with dissonance and detail (a small Coca-Cola logo tattoo-ed on one child’s arm, two children with similar insignia on their wrinkled shirts) amidst an effectively animative display of the EP’s lyrics that it should stand as a true watermark for a certain approach to album packaging.

All that said, the music on Join Us! isn’t without its charm and delight. This 2005 debut EP has the French punk outfit zanily ripping through four tracks of disco-tinged anarcho-punk with colorful interludes. While each of these four songs would find a later home on 10LEC6’s 2006 debut full-length Counselling Orientation, their sequencing here makes for a more concise and punchy statement to a degree that none of the band's later full-lengths would really get around to. By drawing a stop-and-go style-changing sensibility with d-beat and no wave influences towards the stripped-down bass-and-drum sound that characterized many Load Records releases of the time (e.g. Lightning Bolt, The Body, OvO, and Olneyville Sound System), 10LEC6 introduce a propulsive sound still fresh today (oddly reminiscent at times of earlier art school electro like Chicks On Speed as well as more recent deconstructionist punk bands Woolf and P22). Each side of the EP begins with a spoken intro appropriately reminiscent of the dry monologues that began each Crass full-length. On the A-side however those blasphemous monologues are devolved into a stream of incoherent babbling akin to the vocalizations of Phil Minton and Jaap Blonk; on the B-side, it’s the similarly incoherent speech of an auctioneer, the sound of capital moving. Unlike Crass, however, each song here is politically understated and obscure in its messaging.

The band’s later output—which includes a restructuring in 2018 that followed a decade-long hiatus—hasn’t stuck for me the way this EP has. Nonetheless, my recent rediscovery of this lost nugget in my own record collection has me sentimental about the particularities of any collection. It reminds me of the value we each place in items that another might find completely mediocre and the way a creative artifact often branches out with tendrils into the world, infecting others far away, unbeknownst to its creator. Thus, when Emy Rojas shouts “Join us / We want U,” on “Intestinal Skirmish,” I’m inclined to accept, even after the signal has faded over the years. —Leah B. Levinson

Portland Bike Ensemble - Live In Japan 2006 (Olde English Spelling Bee, 2009)

It’s often the case that albums produced with what might be considered novelty items or other typically non-musical objects have a goal of achieving something more conventional and rhythmic than totally abstract. I’ve heard music made with children’s toys (Toygopop, Elementary, etc.), vegetables (ONIONOISE), and even pure field recordings (Of Water, Land, & Sky), all of the unusual “instruments” played or otherwise manipulated to yield largely accessible rhythms and structure. In relation to a somewhat opposite approach of producing formless, textural soundscapes, I wouldn’t say the aforementioned is more or less difficult or rewarding, just different. Mining both the musical and the purely auditory properties of the things that surround us every day are equally rewarding pursuits, but it’s still true that I encounter the former much more often than the latter.

So, needless to say, when a friend randomly gave me a copy of the Portland Bike Ensemble’s self-titled debut on Olde English Spelling Bee (only $8, apparently), I did not assume its contents would be freely improvised music using amplified bicycles—an obliviousness that made my first listen of the 2004 LP even more memorable. The expositorily-named ensemble gathers in groups of two to three bicyclists (a new definition, if you will—not one who rides bicycles, but one who plays bicycles) in studios, art spaces, churches, and a variety of other environments with a motley, Voice Crack-esque arsenal of custom-built bikes and parts. The absolutely enthralling success of this approach, no doubt bolstered by the skill and technical knowledge of the improvisers, led me to purchase a copy of Live in Japan 2006, also released by OESB. It documents a city-hopping tour through the famously avant-garde-accommodating country, with recordings that capture the band’s clattering, metallic “discrete cacophonies,”[1] scratching bow strokes, and other unidentifiable sonic coaxes in anything from the solemn silence of a Tokyo Buddhist temple to a small, crowded, stuffy underground venue in Kyoto.

PBE are one of those acts whose intrigue or “novelty” is not at all tied to their music itself, let alone its quality; isolated from their origins (which could conceivably be unknown if the group had chosen a less illustrative moniker) these are lush, considered industrial improvisations, often echoing the best of beloved standbys like Morphogenesis or The New Blockaders... but the fact that it’s all made with fuckin’ bikes makes them that much more interesting to witness, hear, and talk about. —Jack Davidson

[1] Phrase used in the description of Taw’s recent release Truce Terms on Bezirk, another excellent abstract novelty excursion (in this case, with children’s toys).

Writers Panel

Every issue, Tone Glow has a panel of writers share brief thoughts on an album and assign it a score between 0 and 10. This section of the website is inspired by The Singles Jukebox.

Ellen Fullman & Theresa Wong - Harbors (Room40, 2020)

Press Release info: Harbors is a collaboration of composers Ellen Fullman (Long String Instrument) and Theresa Wong (cello), which draws inspiration from the soundscapes, stories and atmospheres that manifest around bodies of water that propagate exchange. Structured around the extended harmonics of the open strings of the cello, Wong and Fullman utilize subsets of these tonal areas to create distinct sonic environments within the piece.

Fullman’s Long String Instrument, a stunning installation of over forty strings spanning seventy feet in length, places the performers and audience inside the actual resonating body, transforming the architecture itself into the musical instrument. Wong has developed techniques that take the cello beyond tradition into a vocabulary more closely rooted in the sounds of the natural world. She captures material electronically, layering textures amplified throughout the space which form an immersive field where figure and ground are in constant flux.

The piece reveals an orchestration of shifting drones, aberrant melodies and glistening atmospheres. Harbors has reverberated many spaces around the world, including: Click Festival, Helsingør, Denmark; Transformer Station, Cleveland; MONA FOMA, Tasmania; Centennial Hall, Sydney Festival; The Lab, San Francisco; and Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit.

Purchase Harbors at Bandcamp.

Vanessa Ague: Ellen Fullman’s Long String Instrument, a project more than 30 years in the making, is a marvel. Its forty 70-foot long strings lay taught across a room; to play the instrument, Fullman walks between the strings, fingering them with rosin-coated hands. The sound is resonant and crisp, with a hint of nasal crunch. On Harbors, we’re unable to see the massive installation, but its electrifying reverberations make up the backbone of each of the album’s mystical pieces. It works in combination with a textural cello—performed by Theresa Wong—to create immediately entrancing music that garners poignant reflection through gradual change and melancholy harmony.

Harbors transports us to the quietude of a foggy port, where it’s easy to imagine travelers walking across slippery wooden slats, shrouded in mist. It’s an album made of austere drones, rooting itself in the subtle exploration of string instrument performance techniques. This type of instrumental music makes its grandest statements through the channeling of aura rather than explicit statements, and Fullman and Wong choose to create an eerie sensation with each of the works they present.

The most enchanting of the three pieces on Harbors is “Part 1,” which opens the record with a thin drone that gradually blooms. Wong enters the placid atmosphere that Fullman makes with a punch, quickly exposing the contrast of the cello’s full-bodied warmth with the Long Instrument’s electrified tranquility. The piece’s focus on harmony and long-held chords is reminiscent of Éliane Radigue’s Occam V, or the all-cello version of John Luther Adams’s Canticles of the Sky. But instead of solely centering serene harmony, Fullman and Wong play with grainy and airy textures, blending the cello’s complex, folky melody of harmonics with the continual motion of the Long Instrument.

As a duo, Fullman and Wong lean into textural exploration to drive their droning music out of stagnation. In “Part 2” and “Part 3,” Wong introduces other techniques into her performance, like echoey plucks, bouncy ricochets, and airy glissandi. The result is gripping: there is always a new timbre to notice, even as the harmonies remain in seemingly similar areas. After listening, it’s hard to shake the sense of ethereal energy Fullman and Wong are able to create; they truly achieve the aspirational inner pensivity of deep listening.

[9]

Gil Sansón: One knows what to expect when confronted with an Ellen Fullman record. Her Long String Instrument, blurring the lines between musical instrument and sound installation, will yield variations and shades seemingly without end, and will also always remain the same. By turning a performing space into the resonance box of her instrument, Fullman finds and exploits the particularities of a site for aesthetic ends. The technique and the overall form remains the same, with “drone” being the keyword. The resulting music has a shimmering quality and seems to exist out of time: the slow, shifting sounds don’t have edges, making her music relate superficially to Eliane Radigue or Phill Niblock, while remaining immediately identifiable in its character.

Theresa Wong’s cello adds darker hues, highlighting the bright colors of the LSI. Wong avoids the typical tropes of the instrument, putting the cello on the same path as Fullman’s enormous sound maker by focusing on intonation, natural harmonics and the dynamics of bowing. As such, the music has no evident structure and seems improvised, and the rich harmonic spectra of the cello, especially on the low strings, adds a welcome gravitas that enhances the timeless aspect of the music. The moments in which Wong employs other resources apart from bowing, like the glissandi and knocks on the body of the instrument, are particularly striking in a very subdued manner, making Fullman respond in kind and turning the LSI into a sort of giant banjo to great effect.

Harbors is leisurely paced, meditative but not deliberately so. Each of the three pieces have a distinctive character and tone, the first being rich in low and mid range, the shorter middle piece with their plucked sounds offering a lovely contrast in texture and pace, and the third with their bright and buzzing colors: they form a satisfying triptych.

[8]

Marshall Gu: Fullman’s creation is certainly a unique sound. As best as I can describe it, the Long String Instrument sounds like the cheap drone of a hurdy-gurdy turned expansive, stretched for miles. Played loudly and in short bursts, it can be powerful and even cleansing. But the thing is, it’s not meant to be played in short bursts. Harbors is a 43-minute album made up of only three movements, and the major failing here is that I’m not picturing the San Francisco bay that influenced its creation. No images of water, lighthouses, or other aqua-paraphernalia. Fog, maybe. Package these same sounds under the title ‘Wind’ or ‘Desert’ or ‘Tectonic Plates,’ and no one would be any the wiser. Collaborator and cellist Ellen Wong ought to have helped distinguish Harbors from any of Fullman’s other albums—and certainly, there’s the odd rhythmic burst, lingering in the air until the next—but it’s not enough.

[5]

Shy Thompson: Harbors is an album that, conceptually, is really exciting to me. Ellen Fullman’s Long String Instrument, a thing that is itself a piece of art as much as something used to create art, is probably quite a sight to behold; I would certainly love to see it and feel it in action as it takes complete command of the space it inhabits by fully arresting two of your senses at once. It’s hard not to be fascinated by such an ambitious instrument and daydream about what this fantastical thing is capable of. It’s also difficult for me not to be thrilled by what Harbors draws its inspiration from; I love the sounds of water. Field recordings from the shores of France, Rio de Janeiro, Robinson Crusoe’s Island, and countless other places on this big ball of water remain in my listening rotation despite being functionally all very similar, because the subtleties in the way the water meets the earth in each of these places is deeply fascinating to me. I haven’t even bothered to call maintenance and have them fix my leaky bathtub faucet—admittedly, primarily because my cat likes to drink running water and whatever she wants, she gets, but also because I find it to be a pleasant and interesting sound.

This record was set up to be an easy layup for someone so easy to please, but there’s a problem: the sound just doesn’t nail the imagery at all. Despite the romantic allure of a unique instrument that fills a room—both literally and figuratively—and the promise of soundscapes that invoke the feeling of bodies of water, all I come away feeling is that I’ve just listened to a drone album that I’ve heard plenty of times before. I won’t deny my disappointment is due in equal parts to a matter of taste and lofty expectations, but I am nonetheless crestfallen. I sat in the bathroom after listening to Harbors to confirm that the art installation I actually wanted to hear has been in my shower the whole time.

[5]

Joshua Minsoo Kim: “Never Gets Out of Me,” the opening track on Through Glass Panes, features Theresa Wong’s cello and Ellen Fullman’s Long String Instrument in an elegant pas de deux. While beautiful and sinuous, it’s a bit too easy to get lost in. Harbors is more invigorating: there’s persistent intrigue resulting from varying disruptions of continuous drones. Compared to The Air Around Her, Fullman’s album with Okkyung Lee, these tracks don’t feature a distinct foreground/background or lead/accompaniment dynamic. Compared to the Sean Meehan collaboration, I’m not spending the runtime tracing how individual tones evolve and align. Harbors is all about immersion and re-immersion: Wong’s cello regularly irrupts the space and Fullman readily adapts, and the act of listening becomes one of fighting to remain in this enveloping space. While Harbors is not the most kaleidoscopic of Fullman’s works, it is one that allows for my own participation, and that’s invaluable for a piece of music that’s best experienced in person.

[6]

Samuel McLemore: When I saw that Ellen Fullman had a new duo album with cellist Theresa Wong coming out on Room40 named Harbors, I felt I knew exactly what it would sound like before I even pressed play—and I was basically right! It’s an album of darkly romantic and immaculately recorded acoustic drone, featuring the Long String Instrument’s characteristic wall of harmonic reverberations setting the stage for Wong’s cello.

Instead of being disappointed that my expectations were merely being met instead of exceeded, I found myself pleased at how fully realized and sincerely gorgeous Harbors is. Wong and Fullman have collaborated together for over a decade now, and Harbors has been in the works since at least 2015; the amount of time and effort that has gone into practicing and refining the piece is clear in how elegantly Fullman and Wong compliment each other. Drone for me is often best when it sounds rough and unpolished—when it takes the form of naively ecstatic explorations in sound—but the music on Harbors is clearly as well-rehearsed and well-developed as most modern classical and suffers nothing for it.

Instead, it serves as an excellent reminder of how drone and ambient genres are more capable than expected of controlling and refining their expressiveness without losing the essential spark that brings most to the genre in the first place. This spark is hard to define, but it may be described as a certain attitude towards sound and the act of listening, a combination of humble awe and reverent patience that can make other, flashier approaches sound hollow and empty. Fullman and Wong keep the core of their work emotionally expressive and tastefully restrained—no one should complain.

[7]

Mark Cutler: There is an optical experience one sometimes has looking at a calm body of water, when the sun and a light breeze hit it just right. Under those circumstances, the water’s surface breaks into thousands of tiny, white-streaked peaks, colliding, disappearing and reforming faster than the eye can focus. It’s an effect which cannot be captured on camera, one which overloads the feeble visual system with its thousands of glimmering phantasms, moving, morphing, suggesting a shape which never quite resolves.

This is the kind of water I imagine Fullman and Wong had in mind when composing Harbors. The music certainly does not invoke the rhythms of waves against a beach, or the persistent flow of a river. Rather, placid drones dominate all three pieces, with snatches of melody sometimes forming, flickering by and dissolving again. This sense is amplified by Fullman’s extraordinary instrument, which often sounds like a massive cello but can take on a stunning variety of tones. Halfway through the first track, it starts to sound airy and tubular, somewhat reminiscent of Godfried-Willem Raes’s pneumaphones. On the second, it sounds varying like a guitar, a harpsichord, and even a koto.

Like the shimmering surface of an agitated sea, with its whirling heads of foam and silver dollars of light and fallen, floating stars, it is difficult here to focus on any one element in particular. The effect is pleasantly somniferous. Were I not tasked to review the album, I would have taken my laptop to bed, and drifted off to sleep.

[7]

Matthew Blackwell: Some months ago, a video of this guy was making the rounds on social media. In the interview, William Close breathlessly tells us how he invented his “earth harp” by attaching very long strings to two distant bases, smirking as he recounts his discovery that by using violin rosin on his hands and rubbing them up and down the strings, he could create compression waves that would resonate within the room that the strings, performer, and audience occupy. What he doesn’t mention is that Ellen Fullman beat him to the punch by nearly two decades, inventing her Long String Instrument in 1981. The difference is that she’s not corny enough to go on America’s Got Talent or play the Game of Thrones theme.

Fullman’s playing the long Long String game, though, producing a series of recordings with collaborators like Konrad Sprenger, Okkyung Lee, and now Theresa Wong that will, if there is any justice in the world, outlast Close’s viral YouTube fodder. For this outing, Wong’s cello often inhabits the low registers, leaving Fullman to create sustained high notes that provide atmosphere for her improvisations. I made the mistake of listening for the first time on headphones, which makes these notes thin and piercing. Switch to surround sound, though, and they lift each composition up, creating partials and harmonics that sweep across the room and sound slightly different based on the listener’s position. Even if this doesn’t exactly replicate the live experience, which is how this piece is surely meant to be heard, the difference is enough to make or break the recording.

Where the long stretches of drone, as in “Part 1,” make for pleasant background music, the appeal of this collaboration is in how the LSI and cello interact when they are at their most distinct. Wong’s skill at improvising with low plucked, bowed, and scraped notes makes those sections where she wanders with the most freedom, throughout “Part 2” and in the second half of “Part 3,” stand out. As her silences are filled with the subtle ringing from Fullman’s Instrument, she is able to briefly disrupt the tension only to set it up again, as if appearing briefly in the fog. This makes for satisfying repeated listens, as their interplay stays tantalizingly unpredictable even as patterns suggest themselves. If harbors are places of transfer and exchange in Fullman and Wong’s imagination, then this is a successful, if abstract, representation thereof, evoking the San Francisco Bay that inspired it.

[7]

Average: [6.75]

Matmos - The Consuming Flame: Open Exercises in Group Form (Thrill Jockey, 2020)

Press Release info: The Consuming Flame was composed through the social act of invitation, and the album’s 99 participants are, even for Matmos, wildly eclectic. Some are collaborators that have worked with Matmos for many years (J. Lesser, Jon “Wobbly” Leidecker, Mark Lightcap, Josh Quillen of So Percussion, Vicki Bennett) and some are near total strangers found through open calls on internet forums for contributions at 99 beats per minute.

There are players from the conservatory-trained world of “new music” (Kate Soper, Bonnie Lander, Ashot Sarkissjan, Jennifer Walshe) and figures from the extreme music underground (Blake Harrison of Pig Destroyer, Kevin Gan Yuen of Sutekh Hexen, Terence Hannum of Locrian), as well as auteurs from the world of “noise” music (Twig Harper, Moth Cock, Bromp Treb, Id M Theft Able) as well as writers (Douglas Rushkoff, Colin Dickey) and conceptual artists (Heather Kapplow). There are distinguished alumni and contemporary luminaries of electronic music (Jan St. Werner and Andi Toma of Mouse on Mars, Daniel Lopatin, DeForrest Brown Jr., J. G. Thirlwell, Matthew Herbert, Rabit, Robin Stewart and Harry Wright of Giant Swan) and artists associated with indie rock and folk traditions (Ira Kaplan, Georgia Hubley and James McNew of Yo La Tengo, Marisa Anderson). There are undergraduates who took M.C. Schmidt’s “Sound As Music” course during the final year of The San Francisco Art Institute’s existence. In honor of its fiercely independent tradition of outsider creativity, the album is dedicated to the memory of the now closed art school.

Submissions from artists were subsequently layered onto each other, prompting later recording sessions which then built upon the first wave of contributions. These discrete zones were then collaged into larger and larger units and more contributors were invited to join until, gradually, the “group form” of three distinct hour-long movements emerged. Part exquisite-corpse and part virtual festival, the results retain Matmos’ distinct and unique voice despite the promiscuously open nature of these collaborations.

Purchase The Consuming Flame at Bandcamp or the Thrill Jockey website.

Nick Zanca: I have learned to love the longform as certain listening practices of mine have evolved. Back when my commute still existed, I would often occupy the hour spent on the M train from my outer-borough apartment to my desk job in midtown Manhattan with whatever record by The Necks fit my frame of mind. I’d press play before heading down the stairs and out the door, following the trio’s motif du jour slowly develop while walking to the subway—the denouement would almost always align with the moment I’d pay for a cup of coffee at my spot outside the office and take the elevator up. As someone who struggles in a corporate context, it should go without saying that this was often the highlight of my morning. Contrary to popular opinion, inhabiting these sonic spaces is all about pace over patience; simply pair your daily activities with the right stretched-out soundtrack and sooner or later your life’s commotions will settle to a bearable and breathable speed.

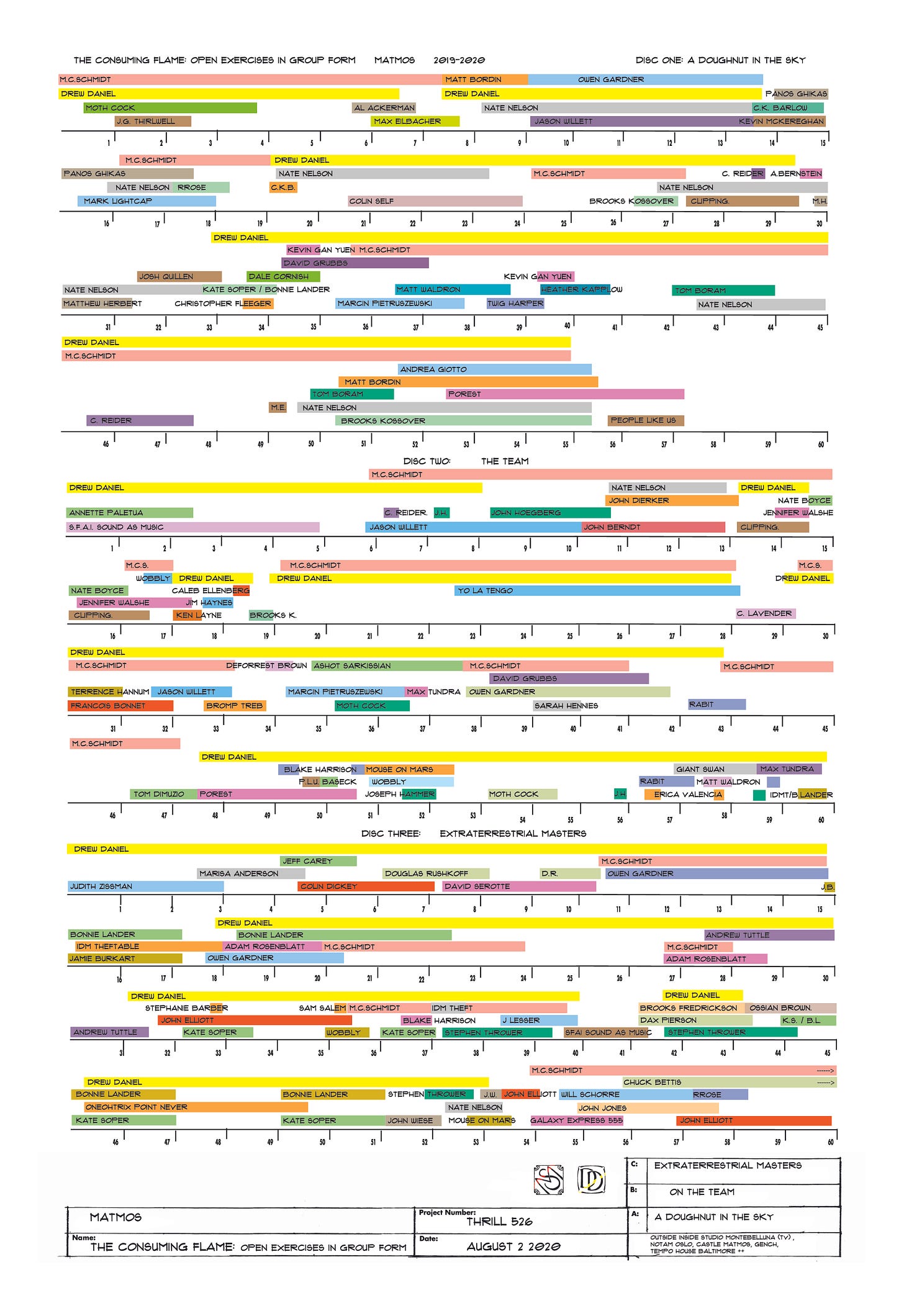

I have likewise long admired Drew Daniel and MC Schmidt’s power-coupling and their constant commitment to self-imposed limitations; whether those constraints are curbed to surgical instruments or Whirlpool washing machines, the duo has always managed to cultivate a rare strain of curious concrète that pushes past the idiom’s prototypical self-seriousness and pursues interdisciplinary influence in its place. I could take this space to namedrop several recorded examples of extended group energy that came to mind throughout these three hours but there are already plenty laid out in the press copy. For me, the superimposed pluralities at play here actually reminded me most of the maximal mechanics of Altman films and Gaddis novels. The latter’s doorstopper-length book JR takes the form of a chapterless capitalist critique almost exclusively written in unattributed dialogue, luring readers into the process of parsing speech patterns and creating relationships for what feels like hundreds of characters; unless you have a guide on hand similar to the graphic Thrill Jockey has graciously provided mapping out a timeline of when contributors appear, chances are you will struggle to find your footing until halfway through. In the act of reading, a narrative can at least function as a glue; in The Consuming Flame, the fixed pulse and the occasional slip outside the grid rarely feels like enough to ascertain cohesion.

That’s not to say the freedom Matmos offers their collaborators never leads to flashes of brilliance—the highlights that come to mind are scattered almost to evade skimming: the spliced voices of Colin Self and Daveed Diggs offer an ideal illegible adjunct to Lower Dens drummer Nate Nelson’s brushed grooves; the absurd speech-synthesis cocktail party atmosphere staged by plunderphonists People Like Us and Porest is comedic gold; the amorphous tectonic shift in textures between our leaders and Yo La Tengo serve as a fleeting ambient respite; the kosmische cosplay between Daniel and Emeralds synthesist John Elliott is actually quite convincing to the point of authenticity. The breadth of substance and style here clearly embodies a crate-digger’s cornucopia at its highs, almost tantamount to the sample-based stratagems of Endtroducing or Since I Left You replaced with organic performances and electroacoustic flexes—really, what’s missing here is a durational backbone.

[6]

Sam Tornow: I’ve never wanted to listen to a three-hour-plus album more than once, no matter how good it is. The pacing is never quite right, and the length always comes off as a show of strength wrapped around a weak concept. Matmos’s Consuming Flame: An Exercise in Group Form, comprised of 99 collaborators whose only guideline was to submit something that’s 99 BPM, is an exception.

Consuming Flame is three hours of gorgeous, hideous, and satisfying sounds masterfully blended to create a feeling of propulsion. One-half of the Matmos duo, M.C. Schmidt, nails the feeling of the record in the press materials by comparing the pacing to that of a train—this feels like riding one and passing through Pendleton Ward-inspired villages, the journey filled with joys, horrors, and plenty of psychedelia.

It’s as much of an exercise in group form as it is a celebration of Matmos’s career. Few other experimental artists could pull together such a massive roster of musicians from diverse backgrounds—Yo La Tengo, Moth Cock, Oneohtrix Point Never, Clipping., and 95 others—and even fewer could mix it all into a cohesive, enjoyable record.

I’ve also never written about a record and been afraid of spoiling its content. There’s so many 10- to 15-second gems buried in Consuming Flame: some sections have such satisfying sounds that it’s like watching ASMR, other parts feel so out of left-field that you’ll wonder how the duo pulled it off, and several moments are hilarious. For Matmos, a group that thrives under constraints and themes, Consuming Flame is another notch in their belt. Enter the record open-minded, and you’ll likely leave open-mouthed.

[8]

Evan Welsh: It took roughly 15-minutes to reboot my brain after first glimpsing the contributors chart for The Consuming Flame, which gives off an intense chaotic-energy—the designation of good or bad will depend on the viewer and what level of color intensity their retinas can withstand.

That energy continues into the music as well, as an immensely protean experiment of mass collaboration, which is its greatest asset and detriment. The only direction here is forward—zipping through landscapes of dynamic rhythm, light, and density at constantly shifting speeds between glitchy, claustrophobic environments and open, atmospheric ones. Each moment and section itself is inviting. I kept waiting for boredom to creep in through my headphones but the bastard never came. The diversity of sounds brought forth from all of these creators are mixed into this wonderfully linear musical trajectory. The only problem is, by the time even 15-20 minutes of music passes, the previous sections have completely fallen away beyond my periphery and even beyond my recollection. After three full listens, only a few select moments stuck with me: a hilarious streaming-platform related surprise and the opening of the third CD, which is impenetrably gorgeous.

Perhaps when this album is available in a more compartmentalized form, I’ll be able to linger in each portion more, investigating and establishing a more longstanding appreciation for them, but as is, there is no lingering. Flames do not stagnate, and even though The Consuming Flame is fragmentary and irregular, one principle ties all of its collaborators and unruliness together: propulsion.

[7]

Gil Sansón: Epithets like self indulgent mean little with a project like Matmos. It’s what they do, they take often absurd ideas and run with them. They do have a distinct sonic imprint, though, and this gargantuan new record does seem like an attempt to go beyond their signature sound as far as they can possibly take it. At the same time, the massive amount of collaborators hints at both a pun on one of the typical tropes in contemporary pop and hip-hop and to an actual representation of a network, one that's as wide, stylistically speaking, as humanly possible. Three hours long, with no discernible center, no climaxes, no dramatic arc. Every style imaginable, from druggy krautrock to glitchy electronica and noise, field recordings to avant-garde metal, everything united by a fixed tempo of 99 beats per minute. In a way, it sounds like a year’s worth of The Wire magazine in a blender, as exciting or annoying as it sounds. It also appears like a challenge to people who claim to have a wide ranging taste in music, while at the same time highlighting the influence that Matmos has on many practitioners of today’s music. Periodically, one hears the type of sound pioneered by the duo before a new window of weirdness takes its place:it’s a party and it’s utopia, decentralized and without hierarchy.

But what about the actual music? Unsurprisingly, it’s entertaining and engaging. Active listening for three hours straight is unlikely, and so the listening experience feels akin to aimless internet browsing (or browsing through record shelves, for that matter). Left-field electronica predominates, though, along with some of the tropes of their contemporaries, as if to remind people that this is a Matmos party after all. Does it make any sense to highlight individual moments or contributions? Not for this listener. No doubt some will feel otherwise, and the duo gives them convenient breaks in something of an index. For me, this somehow undermines the strength of the whole, which amounts to a rich stew with many flavors to be savored at leisure.

It’s a success in the sense that it sounds and feels like a Matmos record, and it works on several levels, from off-center lounge music to Stockhausen-like extravaganza (for some reason I'm reminded of Hymnen), it truly doesn’t sound as daunting as it may seem on paper. Of course, one can listen to half an hour and get the same effect—music shouldn’t be an endurance contest—but you’ll be surprised at how fast an hour elapses with this record.

[8]