Tone Glow 024: Still House Plants

An interview with Still House Plants + album downloads and our writers panel on Jessy Lanza's 'All the Time' and Treasury of Puppies's self-titled debut

Still House Plants

Still House Plants are a Glasgow and South London-based group made up of Finlay Clark (guitar), Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach (vocals), and David Kennedy (drums). The three members met at the Glasgow School of Art and have releases on GLARC, Bison, BYM, and Blank Forms Editions. Their newest album, Fast Edit, is a continuation of their oft-kilter rock music influenced by emo, slowcore, free improvisation, and more. Joshua Minsoo Kim had a Zoom call with the Still House Plants on July 22nd, discussing their beginnings at art school, growing both individually and collectively through creating music, their latest album, Sue Tompkins and Life Without Buildings, and more.

Still House Plants (L-R: Finlay Clark, Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach, David Kennedy).

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Let’s start off by saying one thing we love about the two other members in Still House Plants.

Still House Plants: (soft laughter).

Whoever wants to volunteer can start! And you can take time to think, and if you don’t feel comfortable sharing I totally understand!

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: No, that’s cool. (pauses). Okay, so Fin is unbelievably organized and resourceful—

Finlay Clark: Too much.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: and patient! They can put a lot of energy into things and can be really focused. David is— (chuckles). He’s mercurial, that’s a word that often gets put down. Broad thinking in a nice scattered way, it’s cool.

Love it.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: I appreciate you both, you’re both good.

David Kennedy: (mutters).

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: Don’t be shy, man! You can say it.

Yeah, don’t be shy! (laughter).

David Kennedy: I think Jess is, most of the time, pretty correct with stuff (laughter). And Fin is very, very accommodating (laughter).

Finlay Clark: David is probably one of the funniest people I know, which is a really nice quality. If I have something to talk about, twenty minutes in I’ll forget because I’ll be laughing at something. And Jess is a singular being. You’re—there’s no one else who’s even close to being similar to you (laughter). You’re your own being, which is really hard to achieve.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: Cool. (laughs).

Thanks for sharing, I really appreciate it and it’s nice to hear. Something I wanted to ask, and I guess we can do this all one at a time: What’s the earliest memory that you have of playing music, and can you see a throughline between that particular memory and how you appreciate, think about, and engage with music now?

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: For me, and I was thinking about this quite recently, I grew up listening to a lot of different kinds of music. I was quite lucky: my dad was really into soul— (internet cuts out).

David Kennedy: (laughs). Such a funny still to stop on.

Right? Incredible (laughs). I’m gonna take a screenshot (takes screenshot).

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: Sorry about that, my internet connection isn’t very good. I was saying that my dad was really into soul, funk, disco and jazz. And my mom was into rock, guitar-driven stuff, stuff with female voices. One of my earliest memories of making music was with my dad. I don’t know what it was but we would make drum ‘n’ bass when I was around at his on the weekend. That’s probably my earliest memory of making music, which was cool because it was very basic software, it was pre-GarageBand. It was timelines, you drag a kick… I don’t know. The way I think about music often is in parts accumulating. Using software, and having that be my early experience, is quite telling maybe.

How old were you?

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: I think I was six or seven, making really bad drum ‘n’ bass—but it was fun! We were trying to work out what the software was, it might’ve been FruityLoops but I don’t know if he would’ve had it.

How old are y’all, if you don’t mind me asking?

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: No, that’s cool. I’m 26.

Finlay Clark: I’m 25.

David Kennedy: I’m 24.

I’m 28, hello hello.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: (laughs).

Finlay Clark: I think that’s a good question because it’s often, “When did you know you liked music?” but “When did you actually start making music?” (pauses). This is probably quite a normal answer but I got a nylon-string, three quarter-size acoustic guitar for Christmas one day and I obviously didn’t put it down at all (chuckles) and then I started to record these riffs I was writing. I was using my brother’s gaming microphone, it was a really long, thin one (laughs). I didn’t have any money so I just recorded these acoustic songs, and because it was a gaming mic it just distorted everything. It sounded terrible. I have the files somewhere, they’re all called “Guitar Jam 1” and I shortened them to “GJ” and it went up to like “GJ100.” It was just masses of files of me just playing stuff, so that was the first time making music—in my bedroom, with a gaming mic.

How old were you when you got that guitar?

Finlay Clark: I was 12.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: Did you play violin before then or was that afterwards?

Finlay Clark: I started playing violin when I was six. My dad, whose guitars you can see here, actually! (pans camera to guitars). (laughter). I’m in his bedroom! He’s right-handed and I’m left-handed so I learned guitar upside-down first. When I was 12 I relearned the blues scale and the chords my dad had taught me, but left-handed. So I had sort of a head start but it was upside-down (laughter).

David Kennedy: I actually have quite a funny one. I just remembered that one of the earliest experiences of music was listening to my mom’s small MP3 player. I remember putting the volume to 15 out of 100 and thinking it was the loudest thing ever—I couldn’t imagine it getting any louder. And then I realized recently that when I listen to music, I put it to like 25 on my laptop, or at least on my old laptop. I was like, “Am I slowly losing my hearing?” (laughter). Another one is that when I first started playing drums, I’d hit lots of pots and pans.

Finlay Clark: Oh, really?

David Kennedy: Yeah, when I was really, really young. Eventually my parents let me get some drum lessons. But I was too scared to ever interact with the teacher. He would try to get me to do stuff but I would not want to play drums around him (laughs). And then I’d play at home but my parents still have never seen me play, ever.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: They’ve seen videos.

David Kennedy: Yeah.

Are there videos of you playing drums when you were that young?

David Kennedy: No, no.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: I was just thinking that they’ve never seen us play, but they’ve seen videos, and that’s the closest they’ll ever get.

How did Still House Plants come to be? I know that David and Jess, you two met at the Glasgow School of Art. I don’t know how Fin came along, exactly.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: Me and Fin lived real close at art school. Fin and David were in the same painting class, so Fin’s the link, I guess.

Finlay Clark: I’m the bridge. So basically, me and Jess—as you’d expect—I found out she’s into singing and playing guitar and then she found out I’m into music so we started messing about. We played together, just me and Jess, at the art school. And about a year into knowing David, I found out he was a drummer. I remember when I found out I was really happy and a bit annoyed that it took so long for me to find out (laughs). You were like, “Yeah, I studied drumming.” So it was quite a natural sort of, “Hey, you should come over to me and Jess’s flat” sort of thing.

David Kennedy: I remember sending songs over, we had the same music taste.

How was that first get together? Do you remember it?

Finlay Clark: It’s foggy.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: I can kind of remember it. What I remember is that, early on, when I would leave the room for more than ten minutes to make some food or some tea, Fin and David would come up with this outrageous rock-y, driving music. They’d be channeling Can and I’d say, “This is not what we’re working on” (laughs). It was fun and really funny. I was really shy.

Finlay Clark: I think we were all quite different, ah there’s so much to say. There was a lot of figuring out, wasn’t there? I feel like we played each other music from laptops, music we were listening to at the time. David was relearning how to play the drums, and Jess was learning how to use her voice. It was like someone learning how to walk, it was like baby steps I feel. That was probably a big part of it, just gaining confidence slowly.

David Kennedy: I also remember when we first played our music, we played a song to your flatmate just before we’d done our first ever performance, and she was always like, “Oh it’s really good” but really… (laughter).

Finlay Clark: Oh, really? I don’t remember that.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: We didn’t write amazing stuff to begin with, but it was all like we were gearing up for our first show, there was a lot of momentum.

David Kennedy: I think we played with Gordon at his house, it was ages ago. We tried to record stuff.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: Wasn’t that after our first show? After me and Fin had already recorded some stuff by ourselves and then you were asked to lay down a drum track—this was weeks afterwards—in a room where we’re all standing in front of a mixer. And there was only a snare, and you were like, “What the fuck am I supposed to do?” and you were just hitting it like a toy soldier (laughter). That was probably our first experience of recording.

What year was this? 2014? 2015?

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: 2015, I think.

How was your first show together?

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: It was great. It was part of an arts festival and we’d applied under the guise that we didn’t know what we were going to present, but we were gonna put on a good show, put up some paintings— (internet cuts out).

David Kennedy: Uh oh (laughs).

Finlay Clark: Was that our first show?

David Kennedy: Yeah, although there was a time when you and Jess played just by yourselves.

Finlay Clark: The intent was just to put on a good show, and to get all our friends along, put up David’s paintings. It was such a sincere, good thing.

David Kennedy: I think the festival had a loose framework for linking up house exhibitions. They would have tour groups go around the city to venues in people’s houses, and when we’d done our first performance it was timed perfectly with this tour group arriving. It was so busy that our whole flat was filled and went down the stairs and out into the street.

Finlay Clark: I don’t know how much you know, Josh, but in the audience was Silja Strøm, who is Fielding Hope’s partner—who runs Cafe OTO. And Joel White [of GLARC] was there. Silja told Fielding about us, and then Joel White started organizing tours for us. That was so unbelievably pivotal. At that show we started relationships with these people and everything domino’d from that. I do remember after each show something good would happen, you know what I mean? We would get another show somewhere else… it never felt like we played and nothing happened. It always felt like everything led to something, which was really exciting.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: We were called Your Hair Cut at the time, which is a much better band name (laughs).

Finlay Clark: Yeah, it is.

Wait, what were you called?

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: (slowly) Your Hair Cut. (laughter).

Finlay Clark: It’s cool, isn’t it? We were thinking of calling the first album Your Hair Cut, were we?

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: I think it was a thing.

Finlay Clark: It was an idea, anyway.

David Kennedy: I remember that we were going to change our name after every show. So we changed it but then it stuck.

Who came up with Still House Plants?

David Kennedy: I don’t know. I think it was Fin.

Finlay Clark: I think it was me (laughs). I don’t want to admit it because it’s no good. It was just for fun. I remember sitting on the sofa, laughing about it, and little did I know…

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: It comes from thinking about ensembles with three words like Red House Painters.

Finlay Clark: Yeah, I was into Red House Painters at the time.

Oh, I’m so into them. They’re my most played band of all time.

Finlay Clark: Oh, you know the very famous “Katy Song,” you can hear the influence.

I don’t think you should feel that Still House Plants is a bad name! I think it’s a really good name!

Finlay Clark: Yeah?

I think the three-word name thing you mentioned is important, but even the fact that each word has a similar amount of letters… it flows well and there’s an austerity to it, but it feels very pretty—it kind of embodies the band, it makes sense!

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: That’s really nice. I guess we always hear it as flippant because maybe it was flippant initially. But also whenever someone asks what our band’s called they always say, “What?” (laughs). It’s not difficult but it’s syllabically off-kilter or something. Something about it makes it so they can’t hear it.

Finlay Clark: We knew about the Still House Group in New York, which is an art collective, and at our first show we had all our plants in front of us like a wall, as like a barrier between us and the audience, so the name made sense with the show. So that’s where it came from—the Still House Group and all these plants around us.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: They’re a product of total privilege and not exactly an inspiration—we just liked the words.

I’m into it. I was wondering about this earlier, but do all of you paint?

David Kennedy: Yes.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: (at the same time as Kennedy) No. (laughter). I mean, we all make stuff. I guess I said no because I’m not trained in any way. Though I doodle, I wouldn’t say that I paint.

David Kennedy: That painting course, you could do that course and never do any paintings ever.

Finlay Clark: It’s very open, yeah. I think the answer is that we all don’t paint, but to expand on what David said—it was such an open course that you could start a band and use that documentation as performance art.

I’m not a musician, but as a writer, one of my favorite things is finding connections between different mediums of art. I’m really into perfumes, so I love trying to find a good perfume to pair with an album so I can better appreciate the music and the perfume. Which I guess is to say, what’s the purpose of having the paintings at the show, having the plants—all these extramusical elements? And how does the art you create outside of music relate to or impact the music you create?

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: Quite a difficult one. I always find it hard to find a link, I don’t see all these things as so different I suppose; they’re all just another part of the toolkit. At the beginning we were using what we had around us, using these things of value. David’s paintings were really good, we were really into them, and it was quite natural to include them. We did other things where Fin’s tapestries would be used. I guess it’s nice to have control over every element of your work. It’s all connected but I don’t know how to eloquently say it.

Finlay Clark: I think you’re quite right. We’d all just gone to this art school and you have masses of energy at that point and we all just wanted to do stuff. It was like, “What can we do? What do you do? What do you make? Where can we do this? Let’s find out what community halls we can do this in.” We went to Kinning Park Complex and it became, “Okay what do they have there? They have a piano, let’s write a song to piano.” It was all about asking what we could do and going from there. It was quite playful.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: It was cool to let music speak for itself. We did a lot of collaborative things and worked with dancers and we’ve done that intimately, but we have allowed music to just exist in a bar. It’s about what tools are at hand and how to be generous.

I guess it’s good that Fin is resourceful then.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: Definitely, definitely!

David Kennedy: Sometimes I feel the artwork and the music to be really separate and really different. I do remember at a certain point we were trying to think… (pauses) at Kinning Park Complex it was just playing a show that happened to be an exhibition of our work. They don’t really interact that much really.

Finlay Clark: We did our first show with these paintings around us, we did the Kinning Park show with our work around us, and I remember thinking, “Do they necessarily communicate with each other?” If you perform in an exhibition space, is that really one thing or is it two separate things? I don’t know if we’ve ever said it so explicitly but we kind of just started performing at one point—right now we just do musical performance and I think that’s stronger. I don’t know if we came to that decision quite so clearly but perhaps it was teething at the beginning, like “What works?”

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: When you’re doing something yourself as well, when it’s structured around just you, we got access to these spaces and we were like, “Okay it’s a big blank room, there’s no stage, we have to make it presentable, make it interesting.” It’s a bit like hiding when you’ve got big objects in a room, not hiding but, like… trying to be hidden or a bit shy when you’re the center of attention.

We often think about our music as three separate people coming together, it’s kind of a collision. We can be very reactive and we know each other very well, but we are three very different people and we do things quite differently, so there are always these tensions and things—in a good way!

Finlay Clark: We need that. For lack of a better word, a good relationship is one that’s kind of challenging. If there’s fighting that means that both parties grow, you know? If it’s all eased then what do you get from that? At the beginning I think it was like, “Let’s do installations with every show!” and for me, it became more and more separate further down the line. By the end, the paintings I was making were so closely related to emotional experiences; I haven’t touched anything since art school because it was so laden with emotion. I just left it, graduated, and went on tour. I haven’t done any painting at all; I quite liked it at some point, but it became too personal, you know? (laughs).

Xs (Oil, hand-stitched mono-prints on Fabriano paper, 2017) by Finlay Clark.

I like this idea of the band being three different people colliding with each other. How do you feel you all have grown then throughout the years? What do you see when you compare the new album, Fast Edit, with your early material?

David Kennedy: With the most recent one it felt really together in every single aspect. Whenever I listen to the very first recording, especially in one song I hear just how timid I was in the drums, with sounds starting and stopping. I don’t know if I’ve changed so much, but I’m actually able to listen to our music now. I couldn’t ever play the first tape for years.

The self-titled one?

David Kennedy: Yeah.

Oh my God! I’ve been telling people that that’s my favorite EP of the 2010s (laughter).

David Kennedy: I remember not long after recording that, we recorded some tracks with a friend, Murray, in a little cabin. I remember we drank lots of whisky and then watched a Scott Walker documentary and there’s a bit where he talks about recording music. He’d make something and then never ever listen to it again, and I remember being like “Oh yeah, that’s exactly how I feel” (laughs). I’m not like that anymore, though. Which is good, because that means you can actually start to build on it.

That’s what this is all about, right? It’s through this band that you’ve been able to build confidence and feel more comfortable.

David Kennedy: I feel everything with the new record, even down to the design and stuff, it felt like all of us working together quite nicely. I always felt that most of the first tape never really captured how we play live, while the most recent record is us trying to do something that’s not as live (laughs).

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: We’ve only ever recorded straight live. We’ve not messed around much with post-production or anything until this record. And that’s the luxury of time, we literally have time in a space.

David Kennedy: Everything with the first tape is done in one take.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: Yeah, it’s like playing live, but it doesn’t sound like a room. Whereas this one, we’ve somehow managed to make these rooms we play in… there’s space. I like a lot of what we’ve recorded in the past but it took time for me to listen to it as well. I wasn’t a singer, I’d never sung in front of anyone until this. And I didn’t think I could sing particularly well and then I realized I can—I’ve got a really big voice.

Listening back to the early stuff, it sounds a bit like a different person, but not in a bad way—I’ve totally come to terms with it. There was a self-consciousness maybe. Over the years I’ve been able to be more of myself, which helps when you’re really close to people and trying to make stuff and getting at each other’s heads and getting on each other’s nerves and being really annoying. (laughs).

Finlay Clark: Approximately 19 to 24 or 25—those years are so unbelievably formative. People learn so much about themselves and the world in that period of time and we have these snapshots of that maturation musically. I agree with David in feeling together on the latest album. I think there’s this slight disbelief at how we pulled it all together for the last two albums. Just personally there were a lot of mental health difficulties. I just can’t believe that we recorded all that music and played all those shows. [Fast Edit] is definitely a lot better, it’s the most with it, like the person I’ve been trying to be or mature into is there. I felt the most grounded.

It’s cool hearing you say all this because I know you all don’t consider yourself a band, and have talked about how art is a means through which you can get through difficulties. How has Still House Plants helped you in a personal way? And you’ve already shared bits of this already—having more confidence in playing the drums or in singing—but I’m wondering if there’s more you can say.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: Obviously that voice thing is technical, but it’s also about vulnerability and using words and being expressive. For me it’s very cute and, as an outlet, it has been really useful. It’s allowed me to become more self-assured. I’ve gone through really difficult times and I remember when we were recording the Assemblages tape, I was actually kind of a crazy person. I was not very nice to these two (laughs). I was not a nice person, I was very unstable, but I had this outlet. When I listen to that tape I find it hard to hear, but I also think I sound very powerful and in charge, and that’s cool to know.

Going around the world, too. I never left the UK until I left with Fin. I’ve traveled really far now, I’ve met loads of people, I can make strangers laugh—that’s really cool. And cry.

What’s the most vulnerable song for you Jess?

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: One that we’ve played a lot actually, “You OK.” I wrote that when I was—and I still very much am—in love. It’s about uncertainty and I was feeling a lot of that and passion and love. I was just very scared about what it meant and how to live it, how to deliver this feeling. That question, “Are you OK?” is an offering of my kindness or affection or whatever.

Is this uncertainty about this relationship staying the way it was?

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: It wasn’t an uncertainty of the relationship, it was this fear of finding it and wanting it and knowing how it felt. I was never the person who thought I could (in a sweet tone) love anyone (laughs).

Finlay Clark: That’s a massive, massive thing to learn about yourself. It’s huge.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: Yeah, it was cool (laughs).

I’m happy for you.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: Thanks!

Finlay Clark: To bounce off what Jess was saying about it being like a release, there were many points where I was consciously thinking, “Thank fuck that I have this thing. Thank God that I can have this kind of outlet.” This all-round outlet, where I could travel, meet people, titling things, making artwork—it was this all-encompassing thing. It’s obviously tough, but something good inevitably has a tough side to it. It was a really important thing to wrestle with.

David Kennedy: It was like secret powers. I remember being at work, working in a pub, and I was just like, “I just recorded an album and none of you know about it” (laughs). I really hated that job (laughs).

Finlay Clark: Another thing Jes said about traveling is that to begin with, it was as simple as, “Where do we want to play? What countries do we want to go to?” The shows we did in Portugal, it was a means to travel and to see a place. Say that you land in a city that you’ve never been to, by performing at a music festival you often immediately meet people you would get on with because they’re at the same experimental festival.

When we were in Buenos Aires, we met such great people immediately, and it was in this country from the other side of the world. It’s such a heartwarming thing to go to a country you’ve never been to and meet people who are wicked and you really wanna stay in touch with. And it happens over and over and over, and it’s gonna keep happening. It’s such a nice thing to be able to have, I don’t want to take it for granted.

In a feature for The Wire a couple years ago, it said that your group was about “intimacy, collaboration and care.” You know I’m fucking in love with that. How is Still House Plants trying to foster these things, present these things?

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: I think we know what the action of making this stuff together means. We’re good friends, we’re best friends, we’re really lucky that we are.

David Kennedy: We always try to be really sincere.

Finlay Clark & Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: Yeah.

Finlay Clark: I’m really glad that you said that because that’s our throughline to begin with. It felt like a radical, punk thing to play really sincere and quietly. At the beginning I got a kick out of playing really gently in a loud bar or wherever we were playing. It felt confrontational in a sweet way to sing about love and to play gently. Obviously I also play rough but I think sincerity is a good thing to latch onto.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: It’s our hook, I think. It’s interesting because those dynamics—that hard-to-quiet, soft-to-loud, messy-and-neat—this switching of states… we relish in them all, we hold them all. The instability of it is intentional, we allow it.

It’s like a wholesome hedonism.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: (laughs). That’s sweet.

Listening to your band is interesting—oh sorry, I should call you a group, don’t mean to call you a band.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: I’d call us a band.

David Kennedy: We’re probably a band now. (laughter).

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: It’s nice to be a collective but, you know, we play in bars (laughs). We’re a band, we’re a grotty band (laughter).

Listening to your band is interesting because showing it to people leads to comparisons to other groups, and I hear different responses, though obviously there are overlaps. What are the bands that you all are influenced by, either individually or together? You talked about showing each other music when you first started out, do you remember what you’d share with each other?

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: David, do you remember any of the music you’d send? It was a lot of electronic stuff.

David Kennedy: I don’t know, I can’t remember. I think at that point I never wanted to have anything to do with bands ever again.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: David played in a band-y band.

David Kennedy: Yeah I played in a band-y band at one point and it was horrible. (laughter).

Finlay Clark: You got through it (laughter). For me, it was pivotal that I lived with a friend named Peter—he’s in Chicago. I remember the first day we became friends and he was saying something like, “I don’t use any pedals at all, I just go straight into the amp” and I didn’t understand what I was hearing (laughs). That changed everything. He told me to check out Don Caballero, Storm and Stress, Bedhead, Red House Painters—all these bands that used these clean tones. And Jess taught me about loads of stuff, she got me into Björk and Sade.

I love Sade.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: Oh man, she’s the queen. I was listening to all that emo stuff.

Finlay Clark: You were listening to emo bands from Bandcamp that were his friends.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: I liked Dilute and Storm and Stress. I listened to a lot of grime and garage and stuff, and I think it was Fin who showed me Life Without Buildings, or maybe we got into them at the same time. It’s funny because there’s a closeness—they formed at the same school as us, and their set up is also simple.

David Kennedy: I remember seeing Sue Tompkins in the first week of art school, she did a lecture and performance.

Finlay Clark: Oh yeah, in the Mackintosh.

David Kennedy: That stuck with me, it was really cool.

Finlay Clark: I remember it divided the class, half the people hated it (laughs). That was another kind of milestone band we were into, and they were so close as well—she was always exhibiting. And I interviewed her for a school zine, and it was really easy to get in touch. She even recorded some new performances from her iPad at home and we played them out of speakers at the student union for a performance night. I don’t think I ever met her bandmates but she knew of us. That was really key, that record. I feel it really crystallized things for us. And I think you’re right Jess about it being the same set up. That definitely provided some sort of framework.

And then we listened to electronic music, grime music. I remember sitting in my bedroom and I remember the moment we wrote “The House Sound of Chicago” because I was like, “Maybe I should try and play it like a sample?” And then that was it. You can kind of hear that Life Without Buildings influence.

What’s your favorite song from Fast Edit and what does it mean to you? You can also cheat and say “I don’t have a favorite song” or “I have multiple favorite songs,” I don’t care.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: I do like all of it. I’m really proud of “Able To” which has been out as a single. I think my favorite is “Getting Murky.” We built those songs and there were so many variations of them and that was kind of like a year in development. It changes every time we play it live and it’s nice to hear it existing in this non-abrasive way. I like the idea of playing what you are, what you’re doing, and I think “Getting Murky” is a song that does that (laughs).

How do you decide the variation of the song that you record, or is it just a gut instinct?

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: It’s a bit of a luck of the draw, as it is when playing live. It’s just how it comes out.

Finlay Clark: To go back to an art reference, knowing when to step away from something is so hard to develop and I think we kind of got that with this album. It was like, okay let’s move on.

David Kennedy: The first one we were dictated by time, and with this one there was less of that. It felt like we recorded what it sounded like up until that point, almost. I know that with “Able To,” and we’ve played it live, I would take apart the drum kit halfway through. Whenever we play live, the first song [“Pleasures”] has the drum kit all over the place. I have to run between all the bits and try to put it back together.

Finlay Clark: The first song was our opener when we performed and David would move his kit around the stage and once he put it together, that cued the next song. It was quite interesting to figure out how to do that for the record. There’s a lot of moments I’m proud about. There’s a melody on Side A that Jess came up with on the spot.

David Kennedy: That was made up on the spot, yeah.

Finlay Clark: I was also happy about the beginning of “September,” I loved how Jess recorded the vocals on her phone on the way to the studio. Those sort of small things I was really happy with. Personally, my favorite guitar part is on “Do” because it’s just one chord played duh-duh, duh-duh, duh-duh and then it changes to duh-duh, duh-duh, duh-duh. It’s so subtle but it’s one of those things when you play music where the most simple or repetitive thing is so hard to play. The thing with minimalist playing is that your hand cramps up so much (laughter). It’s simple but it’s really painful to play.

David Kennedy: I like all of it. “Blink 2wice,” “Shy Song,” I really like the end of “September.” I’m trying to remember—I haven’t listened to it in so long. I remember not liking the start because it feels so grand, but the drum part slowly stops, the phrasing changes slightly. And there’s that whole extra section at the end of “Crreeaase.” It’s the only difficult drum part—not difficult, but…

Finlay Clark: When we played “Crreeaase” live Josh, it would go into a version of “The House Sound of Chicago” so we had to figure out a way to end the song for the record.

I don’t have any other questions. Is there anything you were dying to say that you want out in the world for people to see?

Finlay Clark: That’s the sort of thing where, when I’m in the shower tomorrow morning, I’ll think of something clever.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach: I don’t have anything to add.

Finlay Clark: I feel like each time we made something—and I think this is quite universal—that there was a satisfaction but there was always more, it could always be better, so to speak. There’s more things to explore, and I felt that each time we put something out. There’s a delay between recording and putting out an album so you’re psychologically ahead because you’re already thinking of what to do next. I think we all just want to keep making things together. I think there’s a good energy and that we have more to say.

Fast Edit is out on August 14th. You can pre-order the album at Bandcamp via Blank Forms (US) and Bison (UK).

SHP’s Picks

I asked all three members of Still House Plants to share some music they’re into. Their choices are presented below, with YouTube videos or Bandcamp pages linked.

Finlay Clark

Thomas Adès - “Arcadiana, Op. 12: 6. O Albion"

Somebody I work with sent this to me recently and it’s so beautiful.

Lawrence Dunn - “Set of Four”

This piece really floored me when I first heard it.

Alexander Hawkins a Is Solinas per il XXXIII festival "Ai Confini tra Sardegna e Jazz"

Blew me away when I first saw this.

Nina Simone - “Pirate Jenny” (Live at the International Jazz Festival in Montreal on July 2nd, 1992)

My friend sent me this recently. I love how stark her playing is to emphasise the crudity of the lyrics.

Hella - “Biblical Violence” (Live)

Easily one of my favourite videos on YouTube, those cymbal grabs towards the end get me every time.

Bluetile Lounge - Live at The Paddo, 1996

I forgot about this until just now, I love the quality of the recording and how the audience sounds over the live music.

Johann Sebastian Bach - “Chaconne, Partita No. 2 BWV 1004”

I adore Hilary Hahn as well as this piece. You can see that one of the comments reads:

Bach titled the collection of which this is a part “Sei Solo.” That does not mean “Six Solos” in Italian (that would be “Sei Soli”). Instead, it means “You are alone.” He composed these in the months after the death of his wife. He used double stops (playing two strings at once) to bring his wife back to life, as it were, as a virtual second violin performer. Knowing that makes these astounding works even more moving.

Whether this is true or not isn’t clear, but it certainly is unbelievably moving to listen to. It brings me to tears every time hear this piece from start to finish.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach

LA Timpa - Equal Amounts Afraid

I love Timpa and wanted them to play at our residency at OTO a couple of years ago, but thought they lived in Canada. Turns out they were living in London. Big love.

Mother MaryGold - “Lean”

Sounds like spinning out.

Iannis Xenakis - “Keren”

Well titled and sped up sounds raging. David and I sometimes send things to each other to play at certain speeds on YouTube. This one playback at 1.5.

Luciano Berio - “Sequenza IXa”

Sounds like garage. Also, his vocal pieces are cool.

Un Département - “Quelle Chaleur”

What better than a song that makes you laugh. The album is good.

Polvo - “Tragic Carpet Ride”

I don’t even listen to much Polvo but this is a good song, and I think Ash Bowie looks related to me. He’s not though.

Daphni - “Sizzling” (feat. Paradise)

[no comment provided]

Tinie Tempah - “Wifey”

Some romantic grime. This song references this next song by Kano, which is better.

Kano - “Nite Nite”

More romantic grime.

Shygirl + Arca - “Unconditional”

I find this ballad play so moving.

Nídia - Nídia é Má, Nídia é Fudida

[no comment provided]

Joanna Pope’s Biochem Project, ‘5 reasons why foraging alone is better'

All beautiful but listen to “Get In.”

David Kennedy

SOPHIE - “HARD”

Its such an oldie now but I’ve just been really obsessing over her music again, I just think it’s so beautiful. This is the first track I heard back in art school, and some of the tracks from that scene can be a bit too saccharine, but this track brings me up. I only recently found out she’s from Glasgow and I really admire how she deals with being a Scottish artist. I met her and Yves Tumor when I sneaked backstage at a Warp night in Glasgow.

Luar Domatrix - “Heavven”

Rudi has played with us loads of times from our first tour and more recently at ZDB in Lisbon. This song disappeared for ages and it’s back again which I’m happy about. He has a new record out soon on our friends label Domestic Exile in Glasgow.

Flora MacNeil - “Gur Muladach Sgith Mi (I Am Weary and Desolate)”

Listened for the first time as lockdown began and thought it was very beautiful. Scottish music is something I’ve not really explored before/yet.

Shellac live on 5.6.2000 at Princeton, NJ

Listened to them for the first time this morning as I swapped my bedsheets, love outdoor gigs like that.

Allie Ormston - Tony Sporano Fashion Inspo.

We played loads with Allie and she played at our Cafe OTO residency—she is so good. Fin is doing some work with her too that I’m really excited about!

@xcrswx - Call Time / Hard Out

New music by Seymour and Crystabel (I think my favourite drummer). We shared bills in person and virtually I love them! Out on Conal [Blake]’s new label Feedback Moves.

Download Corner

Every issue, Tone Glow provides download links to older, obscure albums that we believe deserve highlighting. Each download will be accompanied by a brief description of the album. Artists and labels can contact Tone Glow if you would like to see download links removed.

Jacques Coursil - Black Suite (BYG Records, 1971)

Jacques Coursil—Semiotician, professor of linguistics, specialist in Caribbean literature, and one of the foremost composers and trumpeters to ever play free jazz—died on June 26th of this year at the age of 82. You can read an excellent obit here which lays out the boggling scope of his ambitions, achievements and intelligence, so instead I will focus on what may be his single greatest work as a musician: Black Suite.

Recorded in Paris in 1969 during the height of the sessions for BYG’s infamous Actuel sublabel, and based on a composition he wrote in 1967 which was inspired in equal parts by serialism and New Orleans Jazz, Black Suite audaciously adapts the tonal palette of the latter into the harmonic framework of the former. From Coltrane to Ayler, free jazz so far had been marked by raw, overflowing emotional intensity. The language of standard music had become insufficient to express the emotions inside it, and so instead of merely playing, musicians had to erupt.

Coursil almost entirely avoids what had even then become the cliche of emotional overblowing by slowing down and opening the music up harmonically and rhythmically. Though a sextet, rare is the moment when more than two or three players, including the incredibly sensitive rhythm section, are playing simultaneously. This open space in the composition yawns between the players, and they fill it slowly, abandoning almost all notions of melody, beat, rhythm, and line but never losing the most important element of all: swing. As Coursil himself wrote in 1968:

“A melodic line, a sonic sentence, needs to be organised rhythmically. It needs spirit, swing, but that swing doesn’t have to be framed in a regular metre. An atonal and arhythmic phrase has to contain a certain amount of swing for it not to seem escaped directly from John Cage’s zoo.”

The players range from the criminally under-recorded Arthur Jones on alto sax to the insanely prolific Anthony Braxton on contrabass clarinet—only the 6th time he had ever played on record according to his credits—to French players such as Bebe Guerin and Francois Tusques, both of whom would collaborate later on Clifford Thorntons’s excellent 1971 live album The Panther and the Lash. Each player works hard to balance their contribution against the full sound of the group and is careful to never step over another’s lines. Recorded at one of the most prolific and important moments for free jazz, Jacques Coursil’s Black Suite presaged the work of ECM and The Art Ensemble of Chicago, and is a key record in free jazz—it stands as one of the greatest records the genre has ever produced. —Samuel McLemore

Y. Utsunomia - Tokusa No Kandakara: 91 Pieces of 'C' Educational Kit (Mue Lab / Hören, 2001)

Hopes and Fears, the debut album by avant-prog rockers Art Bears, begins with an unforgettable opening track called “On Suicide.” With sparse accompaniment and a full-throated vocal performance by vocalist Dagmar Krause, the lyrics reflect on the dangers of the mundane—“melancholy evenings,” “high bridges over the rivers,” and “the long winter time”—remarking that in a single instant these things can enable a person to throw their own life away. I’ve only heard Hopes and Fears all the way through twice, but this track has held a spot in my memory for probably ten years or more. I return to it often, when I need a stark reminder to be wary of how my surroundings are pulling against my mental health.

Years later I would revisit Art Bears with a new perspective and a greater curiosity for the history of European progressive rock, and I listened to the entirety of The Art Box, their collected works in one package. Discs four and five of the set contained new material, called Art Bears Revisited, which featured remixed takes on Art Bears tracks by other experimental artists. Not many of these tracks left an impression on me, but one stuck out: Yasushi Utsunomia’s “Tokusa-No-Kandakara (91 Pieces of ‘C’),” a reworking of “On Suicide” that is so radically different that it is nearly unrecognizable. The title of the track refers to ten treasures gifted to a shinto shrine by a prince from a far-away land, and upon hearing the track one gets a sense for why this obscure reference might apply; it’s made up of spliced-in elements that have nothing to do with “On Suicide”—sounds of chirping birds, the whimpering of a dog, some liquid sloshing around in a container, something fragile shattering—laid at the feet of this simple yet powerful track like ornate gifts. It’s a weird and wonderful take on the track that doesn’t concern itself with aligning closely to “On Suicide” the way other remixes on the set seem to.

In Yasushi Utsunomia’s own words, his goal in everything he does is to “create the ultimate form of music.” This is a nebulous and patently ridiculous goalpost, but listening through Tokusa no Kandakara: 91 Pieces of ‘C'‘Educational Kit, you might actually believe he could be onto something. The 28 tracks contained on this disc are all short audio experiments and pieces of what would become “Tokusa-No-Kandakara.” The first seven tracks alone are manipulations of Dagmar Krause’s voice, exploring ways to use what’s there to create something Art Bears could have never envisioned. The unedited versions of the field recordings are all here, as are extended demonstrations of the studio techniques used to make the alien amalgamation of vocal sounds on the finished track. It’s a fascinating process document that turns a three minute remix into a full-fledged documentary in its own right, but perhaps more importantly: it’s the most sincere form of flattery for the source material you can imagine. —Shy Thompson

Taku Sugimoto & Moe Kamura - Saritote / Saritote 2 (Saritote Disk, 2007 / 2010)

Generally, when one compiles a list of their favorite guitarists, someone like Taku Sugimoto is not likely to be who you have in mind; virtuosity is valued, in the sense typically understood when you talk about someone like Hendrix or Prince—technical skill on a full, explosive display. Taku Sugimoto is clearly also a virtuoso to me, in an opposite, but equally impressive way: he chooses every note, flourish, and technique in his vast arsenal with a purpose and restraint that is unprecedented among masters of his instrument. Taku Sugimoto has been around. His long career has taken him through noise rock, free jazz, psychedelic rock, European-styled experimental improvisation, and beyond. He began his solo career with a bevy of records that explored free improvisation with a “less is more” philosophy of spreading his actions-per-minute thin and making them count, before settling into a focus in composition where he works with even less to make an even more powerful statement: everything is where it ought to be, and nothing here is any less than necessary.

It’s difficult to imagine a vocal performance over a Taku Sugimoto composition; it is more difficult, still, to imagine that vocal performance coming from Moe Kamura, the vocalist from weirdo chamber pop group Hotora Pikara who is also responsible for writing and performing one of the most infectious earworms I’ve discovered this year. Moe Kamura is certainly not your typical vocalist; she has a uniquely airy voice that glides along each syllable she utters like a paper airplane riding a cool breeze. It’s moving, it’s beautiful, but it’s not an obvious fit to accompany a musician with such a sense of self-control, is it? Truthfully, I could enjoy these two Saritote albums if Moe Kamura’s vocals weren’t here; they contain all the purposeful playing I’ve come to know Taku Sugimoto for, and his deft touch and sense of composition are as apparent as ever.

I say that not to diminish what Moe Kamura has contributed, but to properly set the stage for exalting what she brings to these albums: she’s given me another way to understand Taku Sugimoto. Though she’s brought her tempo down to match the glacial pace of Sugimoto’s compositions and stripped away the more song-like adornments you would expect from her other work, she’s still doing what she does best: floating just above the music, mingling with it, but never taking precedence over it. Kamura’s free-flowing vocals swirl around Sugimoto’s compositions like a vapor, freeing them from the trappings of structure and letting them just be. The explicit beauty of Kamura’s vocal makes Sugimoto’s playing feel more implicitly beautiful; Sugimoto’s music usually makes me think, but this collaboration mostly just makes me feel. —Shy Thompson

Writers Panel

Every issue, Tone Glow has a panel of writers share brief thoughts on an album and assign it a score between 0 and 10. This section of the website is inspired by The Singles Jukebox.

Jessy Lanza - All the Time (Hyperdub, 2020)

Press Release info: The early days of writing All the Time, Jessy Lanza’s first album since 2016’s Oh No, marked a sea change for Jessy and her creative partner Jeremy Greenspan. After Oh No, Jessy left her hometown of Hamilton to go and live in New York. Written long distance for the first time, across Jessy’s new set up in New York to Jeremy’s home studio in Hamilton, and finishing in the recording studio Jeremy had been working on during this period.

Even though the move to New York and the change in remote working was tough, All the Time has turned out to be the most pure set of pop songs the duo has recorded; reflective and finessed over the time and distance they allowed it. Innovative juxtapositions sound natural, such as rigid 808’s rubbing against delicate chords in “Anyone Around,” unusual underwater rushes underpin “Baby Love.” Jessy’s voice is treated, re-pitched and edited on songs like “Ice Creamy” and gestural sounds seem to respond to her lyrics in songs such as “Like Fire.”

A lot of these sounds came from live take experiments using semi modular/modular equipment like Mother 32 and Dfam and Moog Sirin. Jessy says “We got all of the machines talking to one another and would run patterns through. A lot of the little burps and quacks and squiggles heard on songs like “Anyone Around,” “Like Fire,” “Face,” and “Badly” are from those experiments. That’s when I’m having the most fun, making music and improvising through takes of the song and editing together all the best gurgle sounds afterwards.”

You can purchase All the Time at Hyperdub and Bandcamp.

Nick Zanca: The third time, as it were, is the charm. Lanza and Greenspan have now pushed their pastel club-cum-pop ethos toward an attempt to replicate (and by proxy, resurrect) the candy-colored foundation Jam & Lewis built to libidinous lengths. Where production is concerned, I am sold on the funk malfunction for the most part—the occasional burst of chipmunk-soul vocal samples can unkindly date these tracks to last decade, but there’s no denying there are moments on all ten of these tracks that fill the DX-7-shaped holes in my heart. For me, the limit here lies in a lack of vocal variety—Lanza has introduced her anger as a lyrical fuel, but it sits in the propulsive percussion before we hear it in her voice. If she took the risk of a dial up in delivery and allowed us inside the velvet rope, I have no doubt standouts like Lick In Heaven would be sent to the stratosphere; these toplines simply shine too strongly for the hardware to be doing all the heavy lifting.

[6]

Ryo Miyauchi: An important part of Jessy Lanza’s music is how her voice exists in the mix. For her previous album, Oh No, it was easy to project certain characteristics and narratives against her delicate dance-pop as it established a specific, introverted mood. Her sweet, melodic murmurs laid low in the tape-hiss-like murk, cloaking the throwback roller-skate disco; the project resembled a mixtape love letter that would never see the light of day.

Lanza sounds as though she’s come fully out of her shell on her third record, All the Time. Her voice gains clarity as it steps out in front of the mix, projecting an eagerness to get out into the spotlight. But she also uses her voice a lot more playfully, displaying a newfound control to get the exact outcome she wants. While she might have applied effects to her voice to obscure her true feelings, the helium-shot croons and chopped-and-screwed coos make her bouncy tracks more alluring from just how dreamy they sound. The way she essentially harmonizes with different versions of herself frames All the Time as a party for one, but she lures you into herself, to join her on the imaginary dance floor.

[7]

Marshall Gu: I first heard Jessy Lanza’s debut back when it first dropped, and Pull My Hair Back felt sly, sexy and most important of all, fresh. This was before ‘alternative R&B’—honeyed singing over UK bass/wonky/glitch beats—got more and more popular in the following year. I remember thinking at the time that Lanza felt like the ‘voice’ or the ‘face’ of Hyperdub: an actual R&B singer in a label that owes so much to the genre. That’s no more true in 2020 than it was back in 2013, especially now that Burial seems to have mostly hung up the cape. Some argued that her sophomore album Oh No was an improvement over the debut, but I thought it was just a continuation, even though there were some new sounds (notably footwork), the end result was still sly, sexy and fresh.

All the Same is a continuation of that. Other than “Ice Creamy,” where the vocals are shifted down in the way that was all the rage this past decade, all of these songs vibe for nights on end. The sound design is excellent as always, whether it’s the squeak of the pitch-shifted vocals on “Anyone Around,” peaking in and around her vocals, or the ’80s pop drum programming on “Like Fire.” Early-highlight “Lick in Heaven” features her most direct hook yet, “Once I’m spinning, can’t stop spinning,” before handing it over to a synth line to spin listeners around. The sexiness comes from the vocals and the lyrics, like the playful way she sings “I do want you badly / You know I do, daddy” in a way that doesn’t draw attention to that word. The slyness comes from the sounds, like the way she plays with footwork’s heady rush of drums and vocal samples on “Baby,” which harkens back to her collaborations with Hyperdub’s footstep artists DJ Spinn and Taso. The freshness is everywhere.

[8]

Sam Tornow: All the Time is the anthem of a world where golden hour never ends, cotton candy clouds float in the sky, your crush is always blowing up your flip phone, and the seaside highway goes on forever. Jessy Lanza and her creative partner Jeremy Greenspan of Junior Boys have created a complex, detailed take on pop and r&b that never loses its danceability; it’s a double-sided coin of heartfelt, bouncy instrumentals and catchy vocal lines capable of swirling around the listener’s head for days.

Lanza and Greenspan avoid the airless production of a lot of modern pop and R&B production, opting instead for a light, reverb-heavy approach. In most cuts, Lanza sounds a few feet back from the mic, giving the feeling that she’s belting away her favorite songs without any knowledge of being recorded. It’s a gentle step away from the YMO-manifesting instrumentals that appeared on 2016’s Oh No, a record where Lanza leaned more heavily into pop than R&B, the opposite of what’s happening on All The Time. It’s a pop album that sounds human.

Much of the album’s instrumentals are the result of Lanza’s playful experiments with Moog’s semi-modular ecosystem—via the Moog Mother 32 and DFAM—giving the tones the signature creamy, silky Moog sound that’s been the backbone for countless, great R&B acts since the ’70s. The set up also allows for interaction, automation and modulation between the synth and drum sounds heard throughout the record, leading to gradual timbre and pattern changes that keep the verses and choruses fresh during repeat listens.

There are no lulls on All the Time, at any given moment, Lanza and Greenspan are filling the space with multiple, sensuous melodies. Then, there’s interplay between the drum machines and bass, and one-shot synth fills floating through the mix, which gives the listener a handful of rhythms to latch onto. What I’m saying is: If you’re not grooving around during the chorus of “Lick in Heaven,” you’re heartless. It’s that simple.

[8]

Sunik Kim: This is deconstructed Timbaland, his bubbliest, most cartoonish blurps and clacks whittled down, rearranged, made weightless. Lanza’s dedication to the barest, wispiest minimalism—one that, far from precluding rhythmic impact, actually sharpens it—is a delight to the ear and, more than anything, genuinely unique (an extra impressive feat given the clear R&B lineage she’s working with here). Her pitch-shifted, trick mirror vocals—a technique that’s so often an annoying distraction in other contexts—are fundamental rather than decorative, goofy but not garish. The formula gets stretched a bit thin, the energy wanes, on the album’s second half; but the irresistible strength of songs like “Badly,” with its burpy bass twangs and airy digital flutes, more than carries All the Time's weaker and more forgettable moments.

[6]

Joshua Minsoo Kim: There’s an intoxicating air here, subtle but potent, boozy but light. It’s there in the quasi-coy vocals, the funk ‘n’ flirt of every synth squelch—irresistible is the operative word: Lanza captures a particular feeling of insatiability, one that’s comforted by an ever-present lure. This isn’t music for your honeymoon phase, it’s for the lambent ecstasy of everyday life, when you’ve been in love and your sober thoughts carry that longing: “All I wanna do is love you” goes the title track. “I only want you close to me.”

Maybe that’s why this album, replete with emotions that are more than just love, feels like nothing but. Anger and envy and doubt and pain—it all just points to that ache for sustained intimacy. And for an album whose songs can feel indiscernible, its homogeneity is good and right: this is the sound of an ongoing romance, its dramas and joys and everything else. In my listens to All the Time, I’ve gladly let it recede into the background, enamored every so often by a sticky hook or instrumental flourish. Fleeting as they may be, these moments always grab me: signposts for how satisfying this album really is. It’s like your lover doing or saying something so utterly familiar—so utterly them—and nevertheless being charmed. It’s an album for all those times you’re happily reminded, this is why I love you.

[7]

Ashley Bardhan: This week, I can’t stop thinking about a chicken cutlet hero that I had at the best deli closest to me. It had mayo, tomato, bacon, and lettuce on it. The hero’s major player, the chicken cutlet, was perfectly salted, and it didn't have a soggy side even though it existed in the same physical space as mayonnaise. I ate it at the beach. All the Time makes me feel like I’m eating at the best deli, one with an ugly, spicy mustard-yellow store sign and an owner named Joe. A lot of the songs are fizzy, like how the first sip of ginger beer zaps and kisses the tip of your tongue, and Jessy Lanza’s voice pools into itself with delay and other vocal effects, like granules of sweetener swirling then piling at the bottom of an iced tea.

My favorite thing about this album is how I think I could kiss my boyfriend for its full 38-minute duration. It’s sexy, it’s the moment at the club when the lights go hot pink, blue, purple, your eyes are sparkling, and suddenly, someone is looking at you. On “Alexander,” Lanza asks in a candied upswing, “Would you rather be lonely?” I don't think I would. I love dancing and kissing and bouncing around, but I admit that, sometimes, I yearn for elementary school lunch even more than I do for those other things. The best school lunch comes with a sandwich, a little bag of chips, and maybe a fruit drink. The fruit drink has to make you pierce the pouch with your straw, a delicious act of violence. “Lick in Heaven,” “Badly,” and “Ice Creamy” remind me of puncturing the pouch. Sexuality reminds me of punching the pouch, too. I love my boyfriend and I love dancing. Sometimes your mind starts spinning and you can't get it to stop.

[7]

Evan Welsh: I moved into a new apartment last month and I have yet to put up curtains in my room, and until this weekend, I hadn’t had an AC unit installed. This means in the ten or so days since receiving All the Time for review, my neighbors from across the way have seen me sweatily dance around my room to Jessy Lanza’s bright and sensual electropop and R&B.

Generally, when writing about music, I try to say something insightful or worthwhile, something maybe that makes it seem like I know what I’m talking about and that I belong amongst all these writers that impress me so much, something that strokes my ego while making readers thoughtfully stroke their chin. But sometimes I listen to music and my genuine reaction is unconscious joy and movement. I know the lyrics are full of deliberate introspection on the part of Lanza, and I feel somewhat badly overlooking them in what is supposed to be criticism, but on each listen these songs overwhelm me with a feeling of confidence and the warmth of summer evenings. I just close my eyes and let go.

[8]

Nenet: Reading through Tone Glow’s “Song of the Summer” issue, I meditate on an upcoming blurb for Jessy Lanza’s All the Time. Moved, I read through the words of my colleagues while in the cool shade that the trees outside my apartment reflect upon my room. With my headphones on, I try to find the right words to reflect a level of truth, a balance of impartial view and human emotion: the type of peaceful, reflective mood that only music and writing can provide.

I missed out on writing about my own “song of the summer” piece because I was deep into my version of summer 2020: freaked out, hopeless, and miserably overworked. Without the possibility of visiting my family and dealing with the fallout of having left the city in which I lived for the past 8 years, I scrambled with the deadline; listening and re-listening to Lanza’s record as I cooked, worked, and combed through my social media as we all do, looking for signs of hope that we so rarely seem to find.

It annoyed and surprised me to realize Jessy Lanza, a Canadian pop artist who now resides in San Francisco, made an album I do not like. I reviewed it on my mind, wondering why. The tracks sound fresh, the production is impeccable, her voice is distinct: funny and serious, it hits the listener as a reliable narrator. All the Time is, without a doubt, a good companion for an unexpectedly grim beginning of a decade. “Lick in Heaven” and “Ice Creamy” are versatile bangers that would work at pretty much any scenario: the dancefloor, a long drive, strutting the streets of a very busy city, a late-night grocery run where choosing ripe fruit becomes a moment of introspective pleasure. Diving into all of its 10 songs continued to prove how mysteriously wrong I can be: there is not a single thing out of place, boring or done in excess in Lanza’s release. Yet All the Time falls flat to my ears.

Feeling like a troll, and still very suspicious of my indifference, I re-listened as I saw people I know come together to hype the release. “Duh I love this”, “SO good” and even someone jumping in to say they loved it to later correct themselves and say they “actually haven’t listened to it yet.” Amused and feeling a weight lift off my shoulders, I thanked this opportunity to arrive at a different conclusion. Jessy Lanza’s All the Time might not be my thing, but it could be yours: an unequivocally attractive album for this summer.

[6]

Leah B. Levinson: All the Time. It presents itself as little more than the petulance of a hi-hat ticking; a steady, nervous thrum. Perhaps it’s the work of a cold libido on my part, but All the Time fails to excite. Instead, these ten tracks bend ever so slightly within a gentle haze, hardly reaching affect through their own clouded texture. As a whole, it’s gray and simple, lacking bounce and shimmer, murmuring awash.

Perhaps, because of those qualities, it rises to meet a general and profound dissatisfaction with daily life, the particular and near-universal truth that our moment is profoundly unsexy. But, as it does so, it continues to point elsewhere, to a sexier setting. What does it mean to hardly utter the words “want you so badly?” Set to a one-note melody entirely on offbeats, the phrase should launch itself forward, but instead, finds itself trapped in a mist, yearning without any sense of body, as though yearning itself is a thing of the past. What is this type of wanting? Hardly present, barely evocative, it stirs so little.

Where is the Lanza who relished in her sounds: the rich warmth of her synth or the suggestive texture of a voice? On her 2013 debut, arpeggiated synths made their way to the fore and voices sprayed syllables, simple and dumb: the words “Kathy Lee” and “fuck diamond” repeating, forming a vivid base full of flavor. Once, a voice beckoned a lover sensually: “you can pull my hair back,” evoking the image and act through the words of temptation. On Oh No every verbalized sentiment was given unique sonic shape. “It Means I Love You” sported a build so material and profound that you’d believe its title from the pulse itself. “Never Enough” bounced with frustration, a working towards, “[giving] it all.”

All the Time barely suggests movement or touch. The album’s harmonies are bare, beats are washed out, and textures lack contrast. “Baby Love” is one of few tracks that fulfills its promise, that of a late-morning, gentle ballad. Instead, barring a few distinct moments (a charming aside at the start of “Over and Over“ or the sudden dissonance between the voice and the harmony in the pre-chorus of “Alexander“), All the Time floats by, sugar-free, languid, resting on a mid-tempo memory.

[4]

Average: [6.70]

Treasury of Puppies - Treasury of Puppies (Förlag För Fri Musik, 2020)

Press Release info: Treasury Of Puppies is a new Gothenburg duo made up of Charlott Malmenholt and Joakim Karlsson. Recorded during the first half of 2020, their 8-track debut album for Förlag För Fri Musik brings together a vast amount of influences into something overpowering and genuinely immersive. Treasury Of Puppies approaches a tradition of text-sound compositions with bruised knees and a slingshot behind the back, merging lush Delia Derbyshire-like radioplay-styled narration, the crudeness of unsung cassette underground heroes like Roberta Eklund and the uncompromising methods of early The Shadow Ring stuff. Under the spoken word and occasional singing lies synths, indolent guitars, tape manipulations and a sparse use of field recordings. Part themes from Eastern Bloc children television atmosphere, part private pressed shimmering new age gold, part lobotomized rock n roll/music of a natural high.

Purchase Treasury of Puppies at Discreet Music, Soundohm and Bandcamp.

Matthew Blackwell: Delia Derbyshire, Roberta Eklund, and The Shadow Ring are namechecked as likely points of reference for Charlott Malmenholt and Joakim Karlsson’s debut as Treasury of Puppies, but those artists were all sometimes too far out and confrontational for the fuzzy pastoralism on display here. To my mind the closest comparison is Plinth’s cult classic Wintersongs, which also features glockenspiel, melodica, guitar, piano, bells, field recordings, simple vocal melodies, and remarkably complex aesthetics hidden behind a twee four-track amateurism. Both duos sound as if they were holed up with few resources (pandemic for the former, snowstorm for the latter). And both have created one of the most sneakingly engrossing albums of their kind.

The first track, “Treasury of Puppies,” is an anemoiac theme song for a children’s show that never existed. The electric guitar on “Sapfo Livin’” and “Ljug mit Ut” is as far away from that feeling as the album ever gets, hinting at a rock ‘n’ roll edge. The rest of the album exists between these “extremes,” if you can call them that. Bells chime in a woozy tape hiss, rain patters behind a tentative glockenspiel, and Malmenholt and Karlsson narrate the whole in a gentle Swedish monotone. It’s an album of trial and error and accident. If they get better at their instruments or better at recording they might lose this early magic. But that makes this first outing all the more precious, as every hesitation and small mistake adds to its charm, never to be duplicated, impossible to improve.

[10]

Raphael Helfand: Far too many contemporary experimental artists go to lengths to make their music sound like a relic from the past, but few execute it as well as Treasury of Puppies. Delia Derbyshire and Roberta Eklund are cited in the press release, but the most salient parallel I hear is with Pale Cocoon’s Mayu (繭), the legendary 1984 limited-released cassette that gained a cult-like admiration on blogs and forums in the early 2010s and was finally released on vinyl this year. Stripped of the tape hiss of its bootlegs, Mayu (繭) still sounds like a transmission from another galaxy, a historic text sent from lightyears away. Treasury of Puppies shares this quality, but in lieu of the creepy, carnivalesque synths that characterize the Japanese release, the sounds of the Swedish one are much more quotidian. Echoey organs recall a Schulzian street scene. Dirge-like, muddy guitars bring to mind a death march on snowy nordic ground. Sparse, tactfully-placed field recordings replete with thudding mic bumps evoke disparate but visceral recognitions in each unique listener. And droning, talk-song vocals from Charlott Malmenholt and Joakim Karlsson tingle the spine, not due to any Nicoesque ethereality but because they bring into focus the overwhelming beauty of the dullest parts of our daily lives.

[8]

Nick Zanca: This short and spectral set instantly evokes the same home-recorded monochrome sparseness of those reissues-in-wait that have lurked NTS shows and algorithmic annals as long as lo-fi ethereality has become an archaeological pursuit for collectors of a certain breed. Either this scheme was arrived at organically or otherwise is the result of hours of digital digging and subsequent borrowing; regardless, these rough-and-ready melodies, little-instrument chamber pieces and narrations over sleepwalked tape loops are numbers that have been done enough times to the point of reaching a hauntological dead end. If the language barrier wasn’t a factor for me, perhaps there would be a little more to lean into—instead, I’ll add one bonus point for artwork of the year.

[5]

Sunik Kim: I’m often wary of ‘experimental’ tape worship—music that fetishizes warble, decay, pitching and slowing things down, splicing, garish samples, a sound maybe best exemplified by the ’80s NWW-influenced ‘industrial’ trend—because the end result usually sounds cluttered, bleary, caked in layers of dust and cobwebs, depressing in every sense of the word, try-hard in its heavy-handed forcing of ‘spookiness’ and ‘atmosphere,’ the first two seconds of the Looney Tunes theme song looped, torturously, to infinity.

Based on the press copy, which references the ‘cassette underground’ and ‘tape manipulations,’ I was expecting the worst; but Treasury of Puppies thrillingly transcends the narrow bounds of tape worship with its emphasis on clarity, melody and construction. There are very few obnoxious ‘rewind,’ ‘speed up’ and ‘slow down’ tape effects to be found here—only crystalline shards of bells and chimes, tendriled, spiraling guitars and fractal organs, all carried by an unexpectedly riveting spoken core. The ‘tape’ medium is essential to the workings of Treasury of Puppies—but in the best, most subtle way, it serves the music rather than simply substituting hardware trickery for actual, thoughtful composition. In essence, where tape worship music (that I’m admittedly making a caricature of) prizes decay, waste, murk, ‘darkness,’ Treasury of Puppies is the sound of emergence, the part that comes after decay; a ghost exits the tomb, takes a seat at the organ, and begins to play.

[7]

Joshua Minsoo Kim: There are humans here—they’re talking and singing and playing their instruments—but they don’t feel present; they’re just vessels for lost memories, every dreary note and nostalgic twinkle a sign of what once was. You could point to any number of reference points—The Caretaker, Brannten Schnüre’s droning folk, the Grouper-isms of labelmates Amateur Hour, Theatre of Cyrene’s spectral Satie—but there’s a story-telling quality here that’s conjured up by the spoken word and homespun, domestic veneer. The feeling isn’t quite like telling ghost stories around the campfire, it’s of tradition and reminiscing and preservation, acknowledging that the past can never be fully remembered. It recalls the seductive mystique of a William Degouve de Nuncques painting: familiar, moody, apparitional.

[6]

Mark Cutler: A very nice little diary album, cobbling together all kinds of sounds and sources. There is a lot of spoken voiceover, which sounds interesting, although I have lost most of my Swedish from when I lived there together—and anyway, people from those West coast cities have incomprehensible accents; they’re practically Danes. The music here is sparse, built mostly around looped fragments of sound which feel haphazardly cut and pasted in a pleasing way. Everything has quite an easy, unlaboured feeling. I could think of some points of comparison, but the album’s press blurb already does plenty of that, listing off references from The Shadow Ring to Delia Derbyshire. The music doesn’t live up to these lofty namedrops, but I’m interested to see if or how they pursue this project further.

[6]

Gil Sansón: A rather charming mixture of unapologetic amateurism with vintage avant-garde leanings, Treasury of Puppies is frustrating and satisfying at the same time. The duo seems happy to work in a safe formula of spoken word atop plateaus of looping fragments, while instinctively feeling that sticking to this blueprint is the best way to convey their musical discourse. It often works, in a way that’s a bit hard to describe; I’m reminded of other artists who have a similarly perverse relationship with the song format, like The Shadow Ring or early Royal Trux, albeit with a marked Scandinavian flavor. The lo-fi approach means that the range of frequencies is limited to the mid-range, with plenty of tape hiss and other delights for the discerning ear. The duo seems to revel in the slacker aesthetic—why learn to play your instrument properly when you can expose your limitations deliberately to make a point, and to avoid the trappings of assembly line standard productions?

And yet there is something of a conservative stance that happens as a result of this lo-fi zeal, the formula sometimes feels just like that: a formula It creates a distance from the listener, as in the end there’s not much risk taking (this, of course, may not be what the artists intended, and is more of a personal appreciation). Also, there’s not much here with regard to hooks, and the listener doesn’t really get much of the individual tracks; it’s the whole that’s attractive, a sound world that combines humble sound sources (music boxes, toy piano, melodica, distorted guitar) with the cut-and-paste production style of today’s pop, bringing forward a feeling of childlike wonder.

The tracks have no discernible structure, and in that sense they seem as background for the spoken word delivery. Since I don’t understand Swedish, I focus on the prosody of the language and the deadpan declamation, but the feeling of children’s fairy tale is strong enough to hold my interest. A part of me wonders what could happen to these songs with a more careful production and arrangement a la Piano Magic, but at the same time I feel that doing anything else to these tracks would hamper the charm.

[7]

Samuel McLemore: While clearly indebted to avant forebears, the key to enjoying Treasury of Puppies self-titled debut is to realize that they are essentially just a folk duo. Their aesthetics are simple, direct, even a little bit naive. Plodding guitars, distorted glockenspiel, and warbling tape loops unwind simply and calmly from their starting points, forming the background for monotone vocals which monologue mostly in Swedish on I-know-not-what topics. This here is probably the source of my main disconnect with the record, and it is certainly no fault of the musicians, I simply don’t understand the Swedish language and as such cannot decipher what is clearly one of the most important elements of their music. With their relatively simple arrangements and structures, but without that semiotic dimension, Treasury of Puppies can sometimes sound more like The xx than The Shadow Ring: atmospheric and moody soundscapes for wallowing in your emo feelings. There’s nothing wrong with that, and in fact there’s much to love as long as you keep your expectations in check—check out the melodica and glockenspiel duet on “St. Bernard.” All in all, it’s a deeply charming debut.

[6]

Shy Thompson: As someone who is deathly afraid of forgetting things I really want to remember, records like these freak me out. The interleaving of things that feel old and new—crisp sounding guitar counterbalanced against tape hiss, poetry-reading style vocals over a backdrop of low fidelity field recordings—reminds me of the nature of remembering, which is probably the point, to some degree. The recent and distant past bleeding together, creating new memories out of pieces of recollections that no longer form a complete event in my head—that is absolutely terrifying to me. I had a strange moment upon my first listen of Treasury of Puppies, where I felt as though I remembered hearing this album before even though there’s no way I possibly could have. It may be that this type of music is prone to mess with me, but it might also be possible that it just sounds too much like a bunch of things I’ve heard before.

[5]

Average: [6.67]

Further Ephemera

Our writers do more than just write for this newsletter! Occasionally, we’ll highlight things we’ve done that we’d love for you to check out.

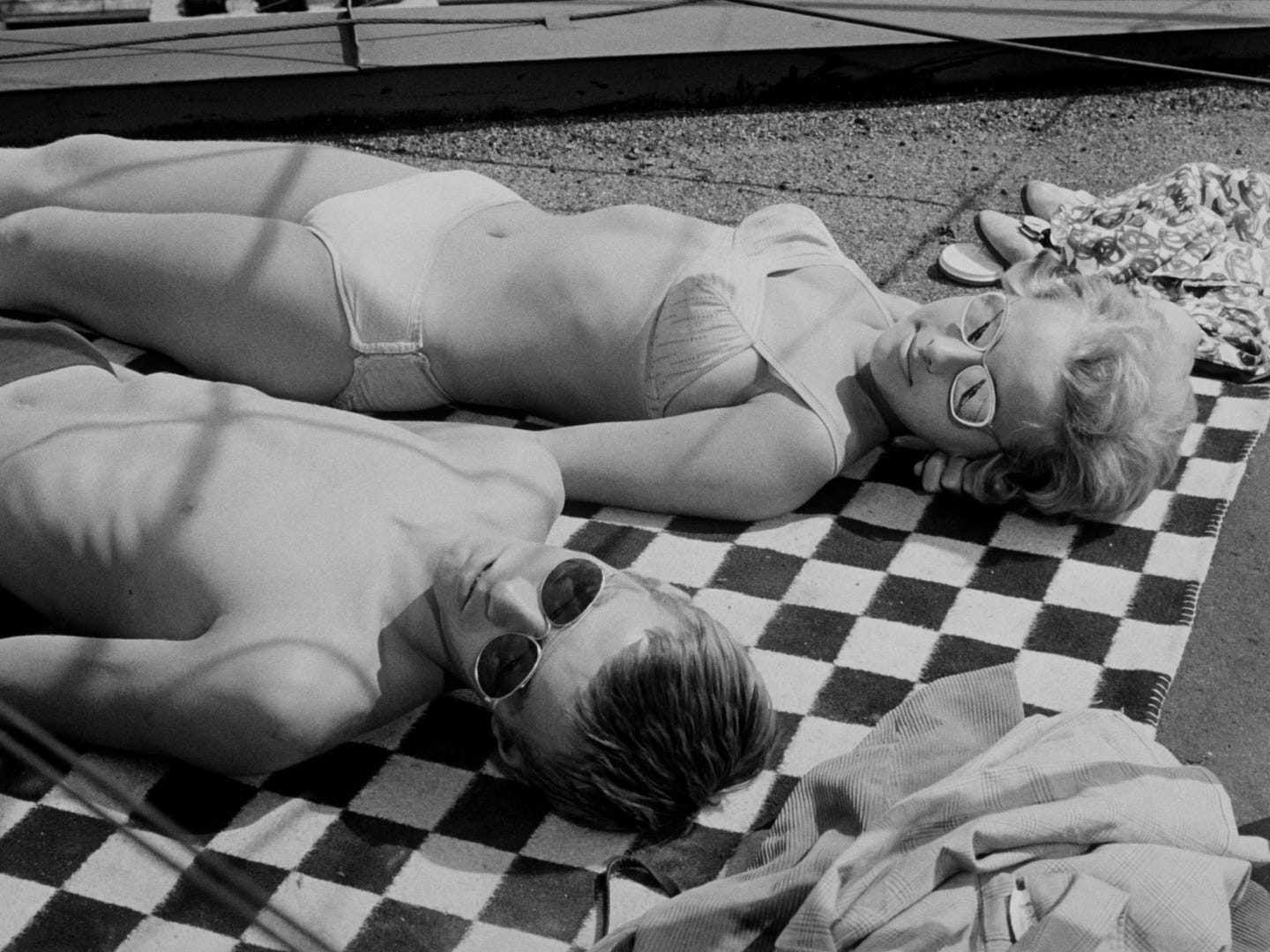

Still from The Sun in a Net (Stefan Uher, 1962)

Vanessa Ague interviewed Clara Warnaar for her blog, The Road to Sound. The two discussed Warnaar’s latest compilation, A New Age for New Age Vol. 2. “We’re reexamining a genre that is rife with cultural appropriation, but at the same time, we’re still here, just younger than the OG new age artists, writing more new age music,” says Warnaar.

Ashley Bardhan wrote about contemporary Bulgarian artists for Bandcamp Daily. “Whether it’s Amek Collective’s penchant for dark ambient, the quickly burgeoning Bulgarian interest in hip-hop, the blending of old and new through folk experimentation, or something else entirely, Sofia musicians are proving that their music doesn’t have to be limited by history or propaganda,” says Bardhan.