Tone Glow 019: Micaela Tobin

An interview with Micaela Tobin + an accompanying mix, album downloads, and our writers panel on Nicole Mitchell & Lisa E. Harris's 'EarthSeed' and Thiago Nassif's 'Mente'

Micaela Tobin

Micaela Tobin is an opera singer, experimental musician and teacher based in Los Angeles who has crafted music both solo and in groups. Her latest album under the White Boy Scream moniker, BAKUNAWA, is an anticolonial missive that was inspired by precolonial Philippine mythology. Joshua Minsoo Kim caught up with Tobin on June 9th to discuss her work, the opera that changed her life, white supremacy, voice healing workshops, and more.

Photo by Suzy Poling.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Hello, hello!

Micaela Tobin: Hi Joshua! It’s so nice to talk to you.

It’s so nice to talk with you as well.

I loved your review and all of the insights into the symbolism and everything. You said things about the album that I didn’t even consciously realize. It was so beautiful, and my family is so excited about it so thank you so much.

Of course, and I’m happy that your family was excited about it. I remember when Raymond Cummings wrote a review for your last album, you were saying how it helped your father better understand the music you make as White Boy Scream.

Yeah, it did!

I hope my review can help with that too.

Oh yeah.

It’s always challenging with the generational divide and with music that isn’t readily accessible to people.

It’s definitely an ongoing conversation with my family and I, but with this album [BAKUNAWA] and the residency at Coaxial and the videos that I made, it’s hitting home more for them. It makes me happy (cheerful laugh).

Can you talk to me a bit about your relationship with your family?

I’m really close with my family. I’m an only child and grew up in Pasadena, California and my mom’s family is here. Two out of my mom’s three siblings and my grandparents were here too, and there are other relatives, like one of my grandmother’s sisters. I grew up really close to the Filipino side of my family here. I’m still really close to them, especially with everything going on in the last couple months with the pandemic and stuff. We’re checking in almost daily—it’s been good.

Where’s your dad’s side from?

They’re from Kansas City, Missouri. I’m in touch with my dad’s side as well. I didn’t grow up around them and a lot of them are still in Kansas City and are spread throughout the Midwest and South. I would see them at weddings and funerals and family reunions but none of my cousins are here. I only keep up with my cousins through Instagram or Facebook, mostly. And then I have one cousin from that side who’s older—he’s an actor and in LA. It was nice to have him here growing up but we’re different generations, so, yeah.

How old are you, if you don’t mind me asking?

I’m 32.

You’re still young!

Ahh thank you for saying that (laughs).

It’s because it’s true!

I’m like (in a worried tone) “Ohh, 32!” (laughter).

Thirties are the new twenties!

Yes, that’s what I feel especially for us millennials. None of us are getting our shit together. All of us were getting our shit together right before the pandemic and now with the resurgence of the movement for Black Liberation it’s like, alright, we’re in this, let’s do this (laughter). Abandon the old life!

Growing up, was your Filipina identity something that you struggled with growing up? Was it something you came to better understand as you were older?

I wouldn’t even describe it as a struggle. Growing up as being mixed, it was just something I didn’t think about much. I think a lot of us first generation kids were kind of assimilated into whatever American culture is or, in my case, Southern California culture. My mother didn’t teach me Tagalog. I got the culture just because my mom and her siblings were here, and my grandparents were alive for the first part of my life. So, I ate Filipino food, my family had all the holidays, and I grew up hearing the language. Even though I don’t speak the language fluently, I can weirdly follow a conversation just by intonation and emotion (laughs).

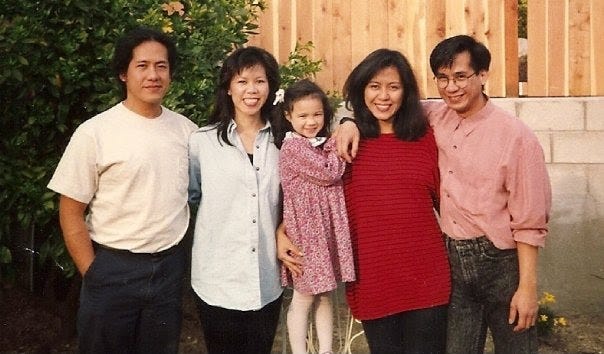

Micaela Tobin’s mother with her siblings.

Right, I understand that.

I tried to take Tagalog lessons. My good friend Anna Luisa [Petrisko], who used to perform under the moniker Jeepneys, is a really big influence on my work. She put together a Tagalog class for all the Filipina artists in LA who are kind of lost in the diaspora—a lot of us are mixed—so we were all taking Tagalog classes a few years ago but it’s a hard language to learn (laughter). You really have to be immersed in it, you know?

For sure. It’s like the same thing for me. A lot of my family is really close and live in the area. The high school I went to was almost completely white and I never learned Korean, but similarly I can understand some conversations just from tone and such.

Yeah there’s something embedded in you that helps you innately know. I think also being mixed, it was a weird… I also didn’t grow up in the church, which I think is pretty unique for a Filipino family—or, at least, I didn’t grow up in the Filipino church. Like I would go and visit sometimes with my grandparents, and I go back once a year now to sing there for a holiday or a funeral but I’m not a Methodist or Catholic. I kind of always felt separate. And I was half white too and that’s a whole ’nother dynamic in Filipino culture too—this pedestalization of being mixed and lighter skinned. I always felt cherished by the greater Filipino community but also singled out, that I was still different.

I grew up in a public school so it was really diverse, so I didn’t really think about my race or ethnicity growing up. It probably wasn’t until I went to UCLA that I started to see a lot of different groups that people were hanging out with based on ethnicity, but I still didn’t feel like I could fit in there with the Filipino Bruins Union or whatever. And then I lived in Seattle for a while making noise and, you know, that’s when I was like, “Whoa, it’s really white up here” (laughter). That was one of the first times I really started thinking about whiteness too—hence the name of my project—and whiteness in the noise scene.

On my previous album Remains, which I made in LA, that’s when I really started thinking about heritage. I am Filipino but I didn’t feel Filipino enough, you know? But I also didn’t want to base my identity off of whiteness. And look at what white supremacy has done to everyone in the whole fucking world—it’s this erasure. I feel like I’m at a place where I can reconcile both halves and embrace them.

Even making this album and doing the stuff at Coaxial for my residency, I was like, “Am I allowed to really dig into my heritage? Can I claim this?” Even that sentiment is white supremacist conditioning. I think it’s a lifetime of work—decolonization, reindigenization—those concepts are really heavy and it’ll take more than my lifetime for it to happen. People have been doing that work for generations and people will continue to do it after me, so I’m just happy to contribute what I can while I’m here.

What goals do you have in regards to contributing to these things? And these can be short term or long term goals.

I think a big part of my practice is definitely being of service to others. I come from a lineage of teachers—both of my parents were involved in mental healthcare and medical healthcare—so as a voice teacher, I do a lot of working with marginalized people in helping develop voices, I work with a lot of trans clients in feeling comfortable with whatever vocal range they want to inhabit. And I do a series of voice healing workshops that help people find empowerment through a resonant alignment of the voice and the body. I’m dedicated to that for the rest of my life—I love being an educator, I love being a mentor.

And then through this project, especially with this most recent album, I’ve come in contact with a lot of other Filipinx artists who are feeling lost in the diaspora and experimental music or experimental performance art, who have found inspiration or visibility through my work. I definitely want to continue doing that. I would say that, just to mention too, that I think it’s important that if I talk about ancestry, I talk about the living artists—my living ancestors—who have inspired me.

The first time I realized that I needed to dig into my identity was when I saw an experimental opera from Anna Luisa—who is also half Filipina—that utilized a reworking of a Filipino nursery rhyme. Everyone’s grandparents would sing this to them, so I would remember my grandpa teaching it to me. When I saw her piece I burst into tears because I realized that I never up until that point—and I studied classical music and Western opera in school—had seen my culture on stage reflected back to me.

Micaela Tobin and Anna Luisa Petrisko in BODY SHIP.

Ah sorry, I’m getting really emotional right now.

I know! Right? We don’t even know that we’re missing that until we see it. That was one of the most profound experiences I’ve ever had. I went up to her after and told her, “I have to work with you, I’ll do anything, I am so in love with your work.” She and I ended up making a piece together called BODY SHIP which premiered at REDCAT and we took it on tour. It tells the story of two sisters who are retracing Magellan’s trading route on the cosmos as a decolonization ritual. She was definitely one of the people who really inspired me to dig into this. Any time I talk about this, I can’t not talk about my community of Filipinx artists who have been doing this work.

Wow, oof. This is great.

Yeah, I’ll send you a link to her stuff. She had an album come out pretty recently and we’re doing another piece soonish. It’s become a virtual piece but we’ll see. We’re called Vibration Group and it’s about a POC group that leaves earth and lives on a space station so we don’t colonize any of the places left on earth. But anyways, this is to say that this is in the air—there are experimental artists doing this. And it’s such an important subject, and especially now more than ever with everything going on.

How has the response been to the operas and music you’ve done that specifically touches on these topics?

The response so far has been really great. I think it’s interesting because the artist base for noise has been historically pretty white.

For sure.

I think that’s shifting a lot—there are a lot of younger people coming up from different communities and it’s beautiful, I’m in full support. But yeah, I haven’t gotten any backlash. It’s hard to say right now with BAKUNAWA because it launched the week of all these big protests so I’m in this place where I don’t want to center myself. The conversation has to be centered around Black lives, you know? All lives don’t matter until Black lives matter. They’ve been doing the fucking fight and we’re all just trying to catch up.

I think what I’m doing is relevant though—decolonization of the Filipino people is completely intertwined with the freedom of Black people. I just posted something on my Instagram story that talks about the history of the slave trade and how it relates to the Indigenous peoples of the Philippines and the colonization there by the Spanish. It just goes to show you that everyone’s history is tied to white supremacy and colonization, and we all need to understand where we’re coming from so we can move forward with grace. We need something new—we have to tear down the systems—but we can’t tear down white supremacy until we understand where it lies within our own ancestral lineage and how it’s affected our own cultures.

I’ve been having more conversations recently with my parents about whiteness, white supremacy and racism, and it’s interesting to hear my parents’ viewpoints and experiences, which are obviously different from my own. What happens when you talk about the topics that define your works with your parents?

It’s different because my dad is white, so he has a whole different perspective. I feel lucky though that both are “liberal” people. I think for my mom and my mom’s generation, talking about this stuff… I get worried because I don’t want to offend or come off combative, you know? Like, “You didn’t teach me Tagalog so now I have to decolonize for you!” That was an unhealthy dynamic—and it was disrespectful.

I went to the Philippines for the first time in 2013 and it was my mom’s first time going back since she came here when she was 25. I met this whole side of the family that I had never met before and it was a profound experience for me. It was overwhelming, it was really heartbreaking, it was amazing—it was all of the feelings. I remember when I was there I got really mad at her. I was like, “Why didn’t you bring me here sooner? Why have we never been here? Why didn’t you teach me Tagalog? I missed out on growing up, knowing about all these cousins and all this family and all this history and I feel like I don’t even fit in here now!” I had a family friend who told me that I didn’t even look Filipino—and I get that a lot. It hurts.

And then I just realized that for my mom, it was so hard to leave the Philippines because when she left, she had to close that door. She had already started a life there—she had a boyfriend, she had a job, she had friends. When the green card hit, she had to leave in a matter of a couple months. My family was also poor so she knew that she wouldn’t be able to fly back and forth, especially in the ’70s. So for her it was closing that chapter and that was the way she survived, she came here—her immediate family was here, her life was now here—and I get it.

So for me now, when talking about this stuff with her, it feels like a more gentle conversation. And it’s more about, like, paying homage. I’m doing all this because I love our family so much, because I’m so proud of what she did, what my grandmother did, what my great-grandmother did and all the way back. And it’s not so much about what we’re not, but what we are.

Growing up here too, I also have a different perspective. I think a lot of us in the diaspora romanticize and long for the motherland and see it as some perfect place when it wasn’t, and that’s because of colonialism and all that. We also need to not lose sight of the fact that our families did what they thought was right—that takes a lot of courage. So, it’s an ongoing and complicated conversation, but it’s always one that I try to approach with love. At the beginning of the album, that’s my mother speaking.

Javier Compound (a family compound) in Taytay, Rizal. Photo by Robert Javier.

I was wondering if that was her.

Yeah. I credit her on the album but she didn’t really realize what I was going to use her for. I definitely feel like I’m more sentimental about this stuff because I’m an artist and I have a career in this so I’m gonna zone in on weird little things about our family that she never would have thought was a big deal.

Oh yeah for sure. My parents ask me all the time, “Why are you listening to all this old Korean music? We don’t even listen to this stuff!” (laughter). Thanks for sharing all that, I was getting teary-eyed, it’s so good. I really appreciate it.

Of course! Yeah.

Can you point to a time when you were working on any of your projects and had a revelatory moment where you understood more about yourself and your identity, or where you realized something about decolonization work?

Yeah, totally. I mentioned this briefly earlier but even just the process of this most recent residency at Coaxial where I made this series of videos—“Sonic rituals for decolonizing the ancestral voice”—I was even afraid to call it that to be honest. I was like, “Is this gonna turn people off? Is this too intense? Am I allowed to say this? I didn’t go to school for this!” It was all these layers of exclusivity—this ivory tower white exclusivity came into play. I had to reach out to friends, the women of color in my life, and ask, “Is this okay?” (laughter). Thank God I have people around me who empower me and are amazing. They were like, “Fuck yeah it’s okay, you’re a woman of color—this is your family and your history!”

There are a lot of Filipinos here doing this decolonization work and then there was this other side of me where I was like, “Are they gonna get mad at me because I’m not doing it the way they’re doing it? I’m not whole Filipino. Like fuck, I don’t even speak Tagalog, is it okay if I use Tagalog in this? Am I a poser?” That’s all internalized racism on myself. I realized that there’s no wrong way to dig into your heritage and learn about it and explore it. There’s no one way to decolonize yourself—it’s different for everyone because everyone’s experiences of immigration and the diaspora are different. There are obviously connecting threads but the nuances of everyone’s experiences are different and beautiful and unique. So I did it in a way that I know how, in a way that’s my style. That was definitely a really powerful revelation. I definitely had to sit down and cry (laughter).

What drew you to the story of Bakunawa?

I stumbled upon this online archive of precolonial mythology called the Aswang Project. I don’t even know how I stumbled onto it, I must have been in some rabbit hole online. This was probably almost a year and a half ago because I toured the BAKUNAWA set in 2018. So I read it and I felt, I don’t know—sometimes you just feel inspiration. It’s like that light bulb—it really feels like a light bulb that goes off! I could feel it in my gut, in my chest—I knew I had to make something from this. I felt so connected to this creature and the story, and I also think the part of the story where people come out of their houses and make noise to scare the Bakunawa was like woah (laughter). I was like, “Yes, I have to make a piece out of this.”

Was that a story you had ever heard when you were growing up?

I hadn’t and it’s funny because when I revealed the album cover to my mom she was like, “Oh! You didn’t know about Bakunawa? I remember hearing about it.” And for this most recent project I was collaborating with my cousin who lives in the Philippines. He was like, “It’s so cool that you’re making music about Bakunawa because barely anyone here knows about it, about precolonial mythology.”

When I was researching stuff, it became extremely clear that a lot of Philippine mythology was not accessible online.

Yeah, I think the Aswang Project is really the most organized archive of it. And then there’s some older books that I’ve managed to get my hands on, from Canada and stuff.

Micaela Tobin with her Bakunawa tattoo. Tattoo by Nicanor Evangelista Jr.

It made it really obvious just how important your album’s existence was because I feel like I would have literally never heard these stories if you hadn’t made it.

Thank you, that makes me feel… wow. Researching it, I was just so excited about these stories. There’s stuff out there but I was like, why isn’t there more? So I had to go get a full Bakunawa tattoo on my arm (laughter). When I get obsessed with something it goes into every corner of my life. I’ve had people talk to me about the album, saying “This story is so cool!” I’ve been having all these Bakunawa moments and synchronicities. Other younger Filipinx artists will be like, “Wow I feel really empowered to explore and claim my heritage and make weird shit out of it (laughter). I think there’s not a lot of experimental music from the Filipino community, but the thing is we could go into another conversation about whiteness and experimentalism and what’s avant-garde—it’s all so layered. I feel like every time I open my mouth or am thinking about all this I need to reframe and reframe and reframe. I think it’s good.

I think about that a lot. A lot of what’s considered experimental or avant-garde is based on what’s been labeled or canonized as such, and a lot of it is just music from white artists.

We were so relieved to hear you were writing the review, to be honest. When I first heard The Wire was going to do a write-up I was like, “This could get weird if a white guy is writing about my album.” (laughter). I mean I’d be appreciative, but I’m glad that it was you (laughs). It’s important, too. There needs to be non-white music critics.

Yeah, there are very few non-white music critics who write about experimental music. It’s mostly old white people, of course.

Yeah. And I love The Wire but that’s what you think of (laughter). But I’ve been really lucky to have visibility and a platform—totally grateful for it.

This conversation is just making me think about how often people won’t consider a piece of music “Asian” unless it explicitly draws upon traditional music from a country, or has themes specifically related to the country’s history or something. That’s something that always upsets me. It isn’t considered “Asian” unless it adheres to the expectations and standards of what something Asian is according to white people.

Totally. It’s complicated too because I’ve talked about this with Filipina artists as well and a lot of Filipino music and art that’s made here in the States takes a lot from Black artists. The cultures can have a lot in common, especially in the Bay Area with the history of DJing, but it’s something that we should continue to talk about and recognize. And I like how right now we’re seeing more non-Black artists saying how their career, their art and aesthetic comes from Black culture.

Micaela Tobin performing live in 2018. Her walis tambo can be seen at 8:50.

With BAKUNAWA, how did you go about approaching the instrumentation? Did you have to wrestle with how you were going to best represent the stories and themes present on a musical level?

I come from a classical background—from classical training—so I always wanna include that. At least on these last three records, it was important for me to not hide that or turn away from it. But I also wanted to dissect what the Western classical canon is and then turn it on its fucking head—fuck those fucking people! But also I love it! (laughter). So I have to reconcile that as well. I’ve been studying it since I was nine.

I can break it down for you. On Side A—the “Bakunawa” side—the aria part, where I’m singing operatically, is me. The piano part I took from Antonín Dvořák’s Rusalka—all the flourishes are from the score, from “Aria to the Moon.” It’s one of my favorite arias—it’s in Czech—so I took the piano parts from that score ’cause also I’m like, “Well, I’m gonna steal your stuff like you’ve stolen from others!” (laughter). Just those flourishes, like the key and stuff. And I wrote the melody. The words are a poem that I wrote about the Bakunawa. And then at the beginning, my mother is reciting that poem which she’s translated into Tagalog. And then that sweeping sound—if you’ve ever seen me live, this is kind of what I’m known for—I have an amplified walis tambo.

Oh yeah I’ve seen that in your performances!

(laughs) Yeah! So that sweeping is my amplified walis tambo, which is like a Filipino broom, essentially. They have them in a lot of Asian countries. They’re basically these straw brooms you use to sweep dirt floors. And then it goes into this section with the bamboo. I have this bamboo rhythm that comes in with the banging pans, and those are rhythms based off Filipino folk dances that I kind of mixed together because I wanted to pay homage. It’s not something you’d really recognize unless you knew those dances, like the Tinikling dance. There are these big pieces of bamboo on the floor and that’s the clacking that comes in.

I’ve seen those dances! I’m a teacher as well, though I’m a high school science teacher.

Oh my God!

Rhea Fowler and Micaela Tobin.

At the previous school I was at, I was a co-sponsor for this club called Asian Pop Culture, and every year the school has an International Night where the different cultural clubs do performances. The Filipino group always does the Tinikling dance.

Yes! It’s so cool, right? I saw a video online of someone doing it with the bamboo on fire.

Whoa.

I need to do that! I need to incorporate that into a live show. I’m writing an opera version of the album as well but we’ll see. It’s supposed to come out in 2021 but it’ll depend on COVID.

Awesome.

So yeah, there are elements of Filipino folk music in that, and I think that’s mostly it for Side A. I go into that drone part where I’m doing vocal beating, and then the end of it is the amplified broom—the walis tambo—where I’m kind of hitting it and singing into it. When I play live, I usually end up with straw in my mouth, coughing up the broom (laughter).

But then Side B, the violin and guitar parts were pretty much composed by my really good friend Rhea Fowler. I grew up with her, she’s a professional violinist and teacher and composer. She wrote the guitar part for “Bituing”—she came up with that. And I just had her go crazy with some drone and noise on her beautiful instrument. I was like, “I know this violin is really nice, but can you just scratch and pluck the strings for five minutes?” (laughter). So that’s what you hear on “Rockets.” And she wrote the part for “Mirrors” too, the guitar line. And that’s really fun—to have someone else come in on the project, because I’ve never had someone make music with me for White Boy Scream.

And Side B is all songs, they’re all shorter. I wanted to increase the accessibility of these pieces. Before that I only had like 14 or 15-minute sides and that’s it. They were “songs” but they didn’t have as much structure, so this time I wanted to challenge myself, like, “Okay I made a long-ass soundscape noise thing on Side A, but what would White Boy Scream sound like with songs?”

I wanna talk about the last track on the album, “Apolaki,” and the video that accompanies it with the blackened teeth. What was that experience like? Had you ever worn blackened teeth before that?

In my research of the album, I found videos and footage of Indigenous Filipino people with blackened teeth and read about the history of it. And then I read on the Aswang Project, this passage that’s written from the viewpoint of Apolaki, where he’s like “You’ve abandoned me for these men with white teeth” so, again, that lightbulb went off and I felt a little ping in my chest that was like, “Fuck, this is so fucking powerful” with white teeth being the symbol of colonialism.

They blackened teeth throughout Southeast Asia and in Japan—it’s a really powerful image—but the way they do it in the Philippines and, I think only one or two tribes really do this now and they’re older generations, but you file down the teeth and rub burnt coconut husk onto them, or you bite down on it and grind it on your teeth. That’s how the song and imagery for “Apolaki” came about. That’s just a lacquer on my teeth but I feel like I never wanna perform without it—it just feels really powerful when I have my teeth like that (laughter). I did that for the video and I did it for the residency too and I feel like I’m a different person with that image.

Oh for sure. Any time you embrace aspects of your culture, especially when it didn’t necessarily define you growing up, it feels super powerful. Even speaking the language, as broken as it may be, still feels powerful.

Yes, totally. “Apolaki” is my anticolonial, anti-imperial anthem. For Coaxial I did an expanded version of that song that lasted 20 minutes and I had people form the QTPOC community send in audio recordings of themselves speaking, singing, screaming, whispering—whatever—the phrase “You can’t erase me.” It was really so powerful hearing everyone say that. It’s like, especially now, we’ve really gotta stand our fucking ground here, because whiteness is the erasure.

Speaking of whiteness, you said that you were going to translate the album into an opera setting. You’ve studied classical music for a long time—can you speak to how you’ve seen white supremacy as it exists within the classical community? And of course it’s there—it’s obvious—but I want you to speak to something you’ve personally experienced.

First and foremost, I was very lucky to have amazing mentors throughout my life, but when I got to college I felt really alienated from the art form. And I couldn’t put my finger on it at the time—I didn’t have the language, or the “wokeness” (laughs)—to understand what was going on there, and why I wasn’t interested in these roles. I was bored and was just like, “What the fuck is this?” It has this staid personality.

There’s the rat race of it all—there’s the pearly white teeth and the gowns, looking pretty and sounding pretty, you know? I was mortified and stepped away from classical music and classical singing for about five years until I went to CalArts for my Master’s where I really discovered that I could mix noise with all of this, that this is all a part of me, that I have ownership of all this and I can make it my own fucking thing.

Micaela Tobin (second from right) during undergrad when she sang the role of Barbarina in The Marriage of Figaro.

What really highlighted it for me—going back again—was seeing Anna Luisa’s experimental opera. Seeing Filipino culture on the stage like that—and it wasn’t like a traditional, proscenium-style setting, it was at Human Resources which is a DIY spot in LA—like, even just having the name “opera” attached to it... all of a sudden I realized the years of absence. For me, that’s really the biggest thing. Like of course opera’s fucking racist—Madame Butterfly, "Three little maids from school are we" [from The Mikado]. You know, there are very few Asian characters and the ones that exist are completely exoticized. But even then it was like of course I wanted to play Madame Butterfly because it was like (through laughter) this is the closest I’ll ever get to playing an Asian character! She’s Japanese! Whatever! (laughter).

It wasn’t until I saw another way to make art and to call it opera that I realized what I had been missing, desperately, for all those years. This is not to throw judgment on anyone else—I know tons of amazing opera singers, POC opera singers—because it takes a lot of courage to go out in that field and be like, “I am who I am and will inhabit these roles and make them my own.” Respect for that. But for me personally, I realized that I wanted to create that visibility for myself and my communities. All this old white man music wasn’t for me.

Photo from "Unseal Unseam," an electroacoustic opera composed by Sharon Chohi Kim and Micaela Tobin. Photo by Katie Stenberg.

What are you planning to do to translate the album into an opera?

So this new music group up in Santa Cruz is so amazing, I love them—they’re called Indexical.

Oh yeah, I know Indexical!

You know Indexical? They’re such awesome people. They’ve been so kind to me, so supportive. I want to translate the album into an outdoor performance on the beach there. That was like the image in my brain—we’ll see with the budget and everything and, now with COVID, outdoor performances are what we’re gonna be doing for the foreseeable future (laughs). That’s how I’ve always wanted it—I’m not super interested in proscenium-style… I’ve written two other experimental operas that were co-composed with my dear friend Sharon Chohi Kim. Those were also immersive, traveling operas that didn’t have a stage. The audience was just in it with us, moving around the space. So it’ll be like that as well.

I’m imagining involving a lot more singers, so I would have a choir. I’d love to even have audience participation where I’d involve some of my voice healing exercises. To me, that in and of itself is decolonization—refocusing on the community’s voice rather than an individual’s, avoiding the pedestalization of one in hierarchy over another. And involving noise and electronic instruments and live instruments out there on the rocks. That’s kind of the loose plan for it. Hopefully it’ll premiere in late summer/fall 2021. There is a lunar eclipse in the summer next year and that would be really cool to do it then (laughter).

That would be really cool.

Right? So that’s kind of the next iteration for this.

A photo from one of Micaela Tobin’s voice healing workshops.

Can you talk a bit about your voice healing workshops? What do those look like?

A lot of us hold trauma and tension in our throats. And a lot of our identity is wrapped up in our voice—the way our voice sounds, the way it feels in our bodies. When I initially started to do these workshops, I posted a question on social media asking, “Do you like the sound of your own voice?” The majority of people said no! I had other voice teachers telling me they didn’t like the sound of their own voice. So the basis of this was that I wanted to start a workshop where people learn to love the sound of their voice.

My wonderful voice teacher who I grew up with would always tell me, “Separate the sound from the feeling.” Don’t judge how your voice sounds—we’re always judging how our voice sounds but we never focus on how it feels. For me, as an opera singer—and as an opera singer in a female-identified body—I was always so concerned with pleasing other people with my voice. I would do whatever it took—I didn’t care how crappy it felt or how much tension I was holding, and the point is always to relieve tension—but in training I did whatever I could to make my voice sound pretty so I was pleasing the director, pleasing the audition judges, pleasing these families, pleasing the audience. I just wanted to sound pretty.

For me, the voice healing workshops are about breaking down that mindset and focusing on: How does your voice feel within your body, because you own your body. And that is really empowering. The workshops involve a lot of breathing exercises. We have to start from a place of ease, and the voice lives on our breaths, so we have to learn how to breathe with ease—most of us breathe with tension, most of us don’t even breathe to our fullest capacities. So even then, I’ve had people break down in my classes because even breathing—even facilitating a space where people can breathe—is powerful.

From there, we go into the basics of pinpointing and dropping points of tension in the throat, in the face, in the spine. And then we move into improvisations so we’re sharing voice. I use a lot of Pauline Oliveros’s Sonic Meditations, which I was turned on to by my dear friend, teacher and current roommate Carmina Escobar, who’s an experimental vocalist from Mexico City. And she also taught at CalArts. So I’m taking these tools that have mostly been hidden away in the canon of experimental music and am using them as tools for everyone.

I wrote a piece called “Scream Piece” that’s an instructional score for screaming, so we go into screaming and yelling and heightened speech. And I also teach a class on this at CalArts but, how to use your voice in that, how to take up sonic space. I don’t know for you but for me, there’s the trope of Asian women being submissive and quiet—like when you’re in public, shh shh shh. I always had a big voice—I’ve always been loud—and I was always told to be quiet. And I didn’t even realize I was being loud, like (through laughter) I don’t know, maybe you should turn your ears down! (laughter). So it’s also turning that on its head and giving people permission to use their voices in this way. It’s very healing for people, and it’s work that I’m still learning and developing: it’ll never end. Usually I hold these workshops in the summertime but I might do some virtual ones or... we’ll see.

What happens if one of your students in the workshop is extremely hesitant to participate because they’re so uncomfortable with how their voice sounds, or with projecting their voice? What do you try to do to get them to a point where they can be comfortable?

Well this is where my years of teaching preschool come in handy (laughter). I must say, I feel like I’m very good at being nurturing (laughter). Not to pat myself on the back but—

No, it’s so good! I love that you recognize it and appreciate that about yourself, it’s good!

Yes, totally. Early childhood education, and especially early childhood arts education is the spark and the light that will save this fucking planet. It’ll save us all. Teach your babies how to be creative and express themselves freely, but that’s a whole other thing (laughter).

Generally, people who sign up for these workshops are at least game to try. There’s a lot of touch in my workshop so in the beginning I always say that if you’re not comfortable it’s okay—it’s your body, you’re always free to just watch. A lot of learning about the voice comes through observation; it’s an instrument of empathy. For me, from all my years studying voice, I can hear someone or watch someone singing and using their voice and I can feel in my body where their voice is resonating or how it’s working. And that’s the point I want to get people to. I let people just watch if they want to take a break. People learn a lot through watching others—it’s empowering watching someone open up their voice for the first time.

Oh for sure. And there’s a parallel there too with these workshops and when you first saw Anna Luisa’s opera.

Oh, totally. Yeah.

Earlier you said that when you get obsessed with something that you get obsessed. Is there something that you’ve been obsessed with beyond what we’ve discussed that you’d like to talk about? And it doesn’t need to be about art either.

Hmm that’s a good question. (through laughter) Yes but I’m, like, embarrassed! No, I’m not embarrassed. I’m like a weirdo. I love reading about conspiracies and paranormal shit and I’m very spiritual too so I have my weird things I like to research in my private, private life. I got really obsessed with this subreddit called Dimensional Jumping (laughter) and it’s archived now because there was so much drama so they had to shut it down I think. The album that came out before this, I put it out on this label, uh—

A Wave Press. The A Vast Room album!

Yeah! For people who don’t know yet, that album was based on this interdimensional jumping subreddit, on the rituals and meditations that are posted on there where, if you do them, you are supposedly able to jump into another dimension or a better timeline than the one you’re currently in. So yeah that was my other obsession (laughs).

Did you ever practice doing those meditations?

No, I was too scared. I just made my own version of them, I didn’t actually do theirs. I made Sharon do one (laughter). I don’t know though if it worked, if she popped into another dimension… I don’t know! (laughter).

What sort of things did they do, and how did that compare with what you did for the album?

There’s this one written meditation that starts off, like, “You are in a vast room” and there’s light on the floor and you see these patterns that are all your experiences and then the light comes up and blinds you—it’s this whole visualization. I used that text as inspiration for different chapters of vocal textures that I made. I drew pictures for myself, I made a score for myself—I didn’t publish it because I’m a terrible draw-er (laughter) but I drew it for myself. I love graphic notation, I love reading graphic scores—such a beautiful way to read music.

Micaela Tobin during the recording of A Vast Room inside Human Resource in Los Angeles, California.

What did your graphic score look like for this and how did they translate with the realizations of the score?

A lot of them were just patterns of lines and shadows forming into different shapes that were either sparse or dense on the page. I would love to do a live version of that with a really good projectionist. I can imagine projections being on the floor, on the ceiling, on the walls and then using a bunch of different singers and have it be immersive, have the audience all wear white so that the projections are all on everyone. We could all interdimensionally jump together (laughter). I wouldn’t let you in if you weren’t wearing white. I like that, I like making the audience bring something that’s not capital to the table. I also got into Kundalini yoga this year (laughs).

How’s that?

You know, the whole yoga community can be problematic because obviously there’s spiritual bypassing and appropriation. And on top of that there’s a lot of drama with a lot of people who have done sexual abuse and harrassment and things like that. It’s been an interesting journey. Luckily in LA I found some amazing queer women of color who teach Kundalini yoga and I trust them. It’s a practice that has really served me and continues to serve me through this pandemic with all the anxiety of being in lockdown, and now this huge portal of activism that has opened up. It’s helped me a lot to find a spiritual, physical practice.

I’m so happy that you have that.

Yeah!

BAKUNAWA portrait. Photography by Katie Stenberg. Hair/Styling by Adela-Maria Pagan. SFX Makeup by Mieko Romming.

You were talking about immersive performances—how important is audience participation for you?

It’s not something that I really thought about before. I really started thinking about it when I was first planning to do my Coaxial residency. Before COVID I was planning to do this immersive live performance. With the subject being about my heritage and ancestry, I really wanted the audience to offer up something when they came in this room, this sonic altar.

And then, I also wanted to relate this to the voice healing workshop, I wanted there to be this sharing of group voice. So that’s where I’m at with that, and now that we’re in the digital realm, I was able to have people participate by having people send me recordings of their voices. As an improviser, I’m confident that whatever the shifting parameters of our reality are gonna be, I’ll be able to figure things out.

You will, for sure.

Yeah.

You’ve done a lot already, you know?

Oh, thank you! I feel like I wanna take a road trip out to the desert, just disappear a little bit. I’m tired! (laughs).

Maybe the answer for this is the desert, but if you could be anywhere in the world right with anybody of your choice, where would you go, and who with?

Well, I’m super single right now, so nobody (laughter). But honestly, I would like to probably be in the desert by myself. I love the Saguaro National Park, and Tucson is one of my favorite places. It’s a very charged place for me, personally—I don’t know why I’m so drawn to it. I was supposed to do a residency there but it got canceled because of COVID but, yeah, I think there.

BAKUNAWA is out now on Deathbomb Arc via the label’s website and on Bandcamp.

Tone Glow Mix

Every now and then, artists will provide a mix personally made for Tone Glow. The following mix has no continuous stream or download available, but all songs are linked below.

This mix encompasses a group of musicians that range from lifelong friends/respected collaborators, to artists I have never met in person but whose work I deeply admire. I tried to focus on artists whose vocal instruments resonate with me, and/or who compose for voice in boundary-pushing ways. Every album on this list is an absolute gem and you should buy it!

—Micaela Tobin

Micaela Tobin’s mix is a collection of the following songs:

Like A Villain - “Tusk”, What Makes Vulnerability Good; Accidental Records, September 2019.

Carmina Escobar - “Recognition Exercises / Ejercicios de Reconocimiento: Part IV”, T Z A T Z I; A Wave Press, November 2017.

Anaïs Maviel - “in the garden”, in the garden; Gold Bolus Recordings, May 2018.

Tyler Holmes - “Rinse (Breath Play)”, Nothing; self-released, May 2020.

Anna Luisa - “The Mystery of Green”, Green; Practical Records, August 2018.

Earth To Jordi - “Whale Channel”; self-released, May 2019.

Nailah Hunter - “White Flower, Dark Hill”, Spells; Leaving Records, May 2020.

TALsounds - “Soar”, Acquiesce; NNA Tapes, May 2020.

Rhea Fowler - “Why?”, Heavy Circles; self-released, November 2018.

Leya - “Wave”, Flood Dream; NNA Tapes, March 2020.

Download Corner

Every issue, Tone Glow provides download links to older, obscure albums that we believe deserve highlighting. Each download will be accompanied by a brief description of the album. Artists and labels can contact Tone Glow if you would like to see download links removed.

Annette Peacock - I Have No Feelings (Ironic Records, 1986)

Annette Peacock’s greatest talent is the swerve. Her 1972 solo debut I’m the One begins boldly with its title track. “I’m the One” moves quickly from abstract fields of sound, to a deep funk pocket, to something like a game show theme, finally climaxing with Peacock’s Moog-processed voice featured over a blues shuffle. The turns there are made remarkable for their groove, a musical virtue which Peacock all but gave up after the deflated reception of her frankly excellent 1979 album The Perfect Release. Her ironically titled, self-released I Have No Feelings (1986) might be her strongest thereafter, expressing through ballad a vibrant stew of collaged sounds and lyrical imagery. Ideas slosh around here in a thick melange, slowly moving towards an ever diversifying blend. The album’s gorgeous cover is by Alfreda Benje. Benje’s work has also adorned many sleeves for her husband Robert Wyatt, a musician whose most abstract and pointillistic compositions are echoed here.

Saturated in a deep, rich blue, few events across this album rise past the surface, instead presenting a dense liquid body worth wading through. The orchestrated, melting delivery of the line “I have no feelings / I feel no pain,” calls to mind the lush hopelessness that Billie Holiday and Ray Ellis provided on Lady In Satin: a heartbreaking murmur, falling apart. “A Personal Revolution” provides one of the album’s clearest moments, with Peacock calling for a sex strike from straight women. She begins the song brilliantly with the solemnly chanted mantra, “No nookie til the nukes are gone” before delivering a direct, spoken call to action: “Women have power over men both sexually and numerically / I’ll leave it to your discretion.” It sounds humorous and perhaps politically impotent until Peacock (in her brilliance) states a decisive, admonishing “no” as the track begins to fade, exemplifying for her troops the very real moment of sexual denial. Sex, politics, and sorrow are often at the crux of Peacock’s work. Here, these themes are essayed from a knowing and sensitive perspective. —Leah B. Levinson

Inuhiko (犬彦) - 話があるなら酒もって来い (Enban, 2011)

Shoko Uehara (more commonly known as Jon the Dog or simply Jon) might be my favorite musician in the entire world. It’s difficult to explain her charm, but when I show her music to other people they just get it. She sings and plays the pump organ, but doesn’t do either particularly well. The subject of her songs range from children’s tunes, improvised stream-of-consciousness ramblings about whatever, or impassioned ballads about her cat Ochonan-san. She often performs dressed as a dog, or sometimes as a cow. Given the opportunity to release something on John Zorn’s esteemed Tzadik label, she chose to provide home recordings in the exact same style and fidelity as she’s always done, rather than do something “special.” She’s definitely weird, but that’s not what I like about her. Jon is aggressively, unapologetically herself, and she doesn’t know any other way to be. She seems unconcerned with fame or broad appeal; she just does her thing and has fun with it. You could approach Jon’s music from a vantage of how “strange” or “outsider” it is and treat it as a spectacle, but I feel like you’d be doing it a disservice—she’s just cool and funny, and that’s enough.

Jon has worked with other musicians on occasion, and her personality is so magnetic that the influence of her collaborators does not even pull the music anywhere close to what you might assume the “center” of that intersection should look like. Jon’s record with legendary producer and music theorist Yasushi Utsunomia was undoubtedly a Jon record despite his production tricks and wild experiments, and the same holds true for this Inuhiko album. Hiko, the drummer that banged out the riotous smashing and crashing on one of my favorite punk albums—Fuck Heads by Gauze—is a pretty magnetic person in his own right. Jon, however, is a laboratory-grade electromagnet, and she is unmoved. This is still a Jon record, and it affirms what I love about her: it doesn’t matter who you are; you’re either along for the ride, or you’re thrown the fuck off. Even if you put her against the wildest drummer you can find and make her yell a little louder to be heard, she’ll still sing her songs about her cat (who is doubtlessly no longer among the living, since there is 16 years difference between this album and the Ochonan cassette), she’ll still play a silly circus tune on her organ, and she’ll still insist she’s a dog and not a human being—and you have no choice but to believe her. —Shy Thompson

expos - <p></p> (self-released, 2017)

In Will Long’s relentless release cycle, this was hardly even a blip. Long consistently puts out some dozen full-length releases every year under his Celer alias, mostly in the form of digital files, which he uploads directly to the internet. At some point in 2017, he quietly uploaded this album to his colossal Bandcamp catalogue. Some time after that, he took it back down.

Still, this album stands out in a couple ways. First and most obviously, it’s the only album Long’s put out as expos, with a barely-pronounceable title that differs greatly from the poetic fragments and imagery Long generally prefers for his album and track names. It differs sonically, as well, from Celer’s typically breezy, ambient compositions. Celer’s tracks are typically built around some instrumental undertones, as though we are hearing an orchestra play, in extreme slow motion, at the bottom of a remarkably spacious well. Over this might waft some gentle, synthesised hums of whirrs, but the prevailing mood is still organic and impeccably serene.

Traces of Long’s signature sound flicker here and there on <p></p>, but only through waves and waves of grainy, heavily processed noise. These tracks are loud, abrasive and irregularly paced, always speeding up or slowing down, so that we are never lulled into any sense of rhythm. Sounds whip between the left and right channels, stuttering, duplicating, tripping over themselves and cutting themselves short. On my first listen, I kept turning my head involuntarily toward the sharp bursts of sound seeming to encircle me.

On one level, everything about <p></p> is a mystery—its inspiration, composition, title, and ultimate disappearance. On another, however, it’s all right there, confronting you, surrounding you. As a Celer album, it is a near-total anomaly, with few precedents in Long’s entire catalogue. Perhaps Long simply felt it would disappoint fans of Celer’s blissful ambience. Yet is a very good noise album, and one that—until now—may never have reached its most receptive audience. —Mark Cutler

Writers Panel

Every issue, Tone Glow has a panel of writers share brief thoughts on an album and assign it a score between 0 and 10. This section of the website is inspired by The Singles Jukebox.

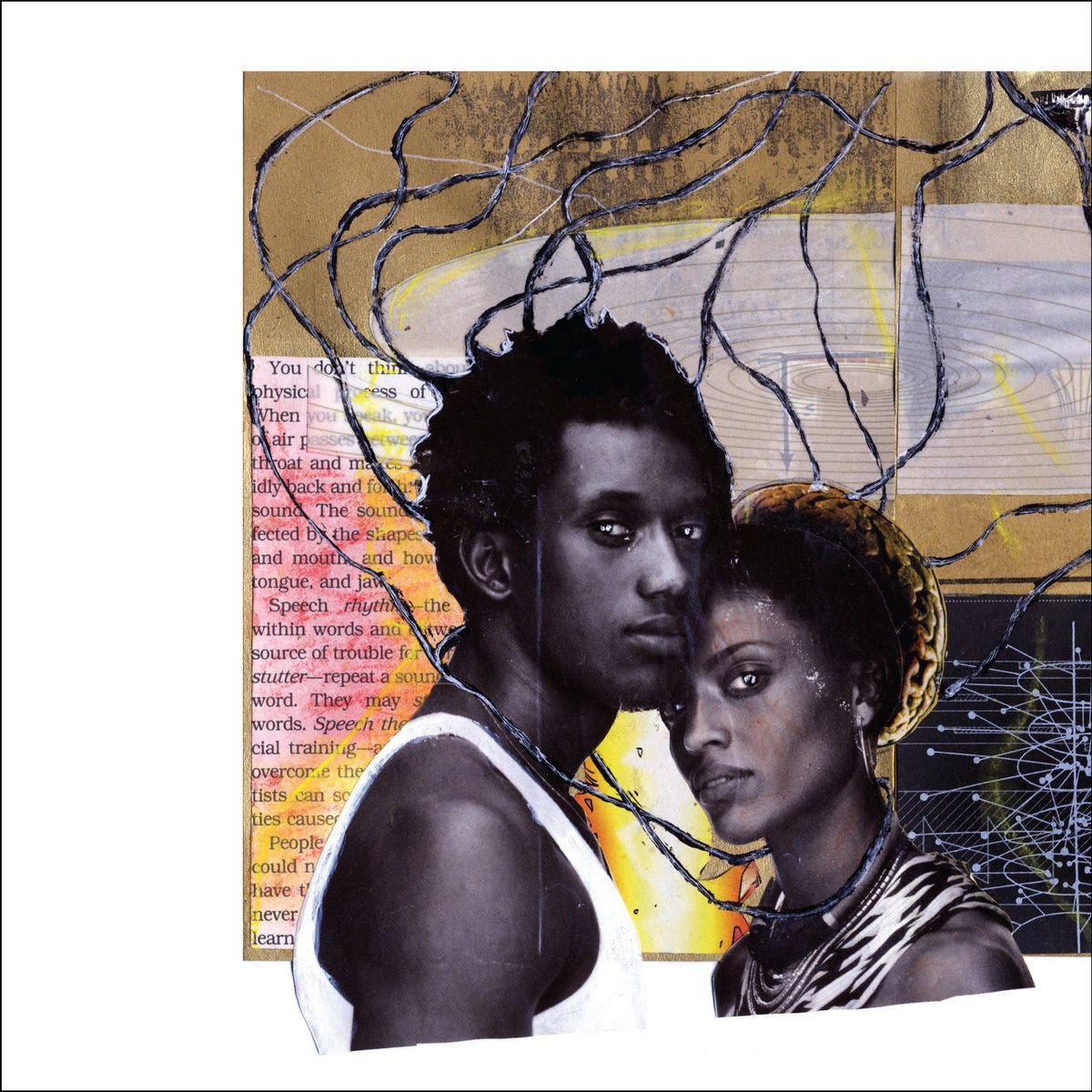

Nicole Mitchell & Lisa E. Harris - EarthSeed (FPE Records, 2020)

Press Release info: The work of award-winning African American science fiction author Octavia E. Butler becomes increasingly prophetic as we move through the challenges of the new century. Her novels Parable of the Sower (1993) and Parable of the Talents (1996) use fiction to illuminate a horrific unraveling of 21st-century America into a despotic chaos where its once-middle-class citizens struggle to survive in an incredibly violent and fragmented reality, void of normalcy, family, and resources. In the 1990s, Butler’s Parables warned readers about a possible disintegration of American culture and infrastructure, among the many risks of tyrannical rule. Within Butler’s storyline, the character Lauren Oya Olamina, a preacher's daughter of African heritage, helps to rebuild her community through offering Earthseed, an egalitarian philosophy and spiritual practice which honors inquiry, independent thinking, and realistic acceptance of constant change.

Inspired by and in tribute to Octavia E. Butler, composers Nicole M. Mitchell and Lisa E. Harris have created their own sonic EarthSeed, also in response to the real chaos and horrific nature of our times. EarthSeed is the third of Mitchell's projects inspired by the literature of Butler and marks a first compositional collaboration between Harris and Mitchell. Mitchell’s two previous recorded Butler-inspired works are Xenogenesis Suite (Firehouse 12) and Intergalactic Beings (FPE). EarthSeed was commissioned by the Art Institute of Chicago and premiered on June 22, 2017. EarthSeed was presented in association with the exhibition of Cauleen Smith: Human_3.0 Reading List.

You can purchase EarthSeed on Bandcamp.

Jeff Brown: Listening to EarthSeed is like walking blindly into a small theater to watch a troupe put on an opera, one that your friend recommended you based solely on your love for Sun Ra, early dada Mothers of Invention, 1970s electric Miles and Henry Cow. The work of Nicole Mitchell is a stand out here—the flute is a wonderful instrument to stretch out and just blow, creating wild staircases of notes with a tone that’s smoother and softer than brass or guitars. The theremin becomes an electronic extension of Lisa Harris, who’s mastered the art of crafting feather-light passages, of allowing her voice to form into bubbling, astral melodies that nod to The Arkestra. There’s humor and laughter in “Yes and Know,” with repeating words adding ostensible levity against the more foreboding sound effects and scratching strings used throughout the album. When it all concludes, you get a sense that this album is a rabbit hole: the art feels continuous.

[8]

Vanessa Ague: EarthSeed sees flautist Nicole Mitchell and vocalist Lisa E. Harris team up for a futuristic musical exploration, drawing inspiration from the work of science fiction author Octavia E. Butler. On paper, this is something I want to love: the radical groove of two virtuosos venturing into the throes of our wildest imaginations. But in actuality, the recording is a series of ups and downs, leaving me with mixed feelings rather than pure appraisal. As a whole, the work is loosely operatic, flowing between freeform spoken word recitatives and winding arias. But the constant jolt between forms is a big reason the music doesn’t feel compelling. The combination of hymnal song and extended techniques in “Whispering Flame'“ creates a haunting and unforgettable mysticism, but this aura is quickly lost with “Biotic Seeds” and “Yes and Know,” two echoey pieces with wavering melodies that do nothing to bolster the clever wordplay at hand. Sporadic bursts of energy and surrealism bleed together on the rest of the album; some statements do pop out—like the clusters of harmony and glissandos on “Whole Black Collision”—but the rest feels like a series of missed opportunities to make the sound and story more engrossing. The most memorable moments come with the album’s final breaths: “Self Transform” closes out the record with an ethereal pulse and touching emotion. It’s a shame that this transformative sound didn’t make its entrance sooner.

[5]

Sunik Kim: This might sound very specific, but the combination of operatic free vocalizations and scratchy, noodly improv is a major pet peeve; something about it is often just deeply irritating to me—it’s what I imagine people who ‘don't like experimental music’ think all ‘experimental music’ is: just pure absurdity. That being said, though much of EarthSeed is undeniably in that vein, there are moments where things coalesce and true beauty emerges: the repetitive, interlocking strings and flutes on “Ownness” pierce through the meandering murk, and the swooping, THX string screeches on “Whole Black Collision”—that collapse into a low synthetic noise cloud, which in turn dissolves into a “Rothko Chapel”-esque string and choral formation—show the promise of this ensemble. It’s unfortunate that the clownish “Phallus and Chalice” had to follow such a peak; this kind of ‘experimental’ vocal work almost always makes me reach for the volume knob in a panic. To be fair, this style of vocalization probably has its roots in scatting, which, though its exact origins are contentious and very possibly racist (this timeline claims the earliest recording of scatting features white entertainer Gene Greene, who was attempting to ‘imitate’ Black musical traditions), has undeniably played a key role in Black music history (from Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong to Linda Sharrock and Amiri Baraka). Unfortunately this doesn't change the fact that I find scatting and free vocal improv extremely hard to listen to. The whiplash of the “Whole Black Collision” → “Phallus and Chalice” sequence sums up EarthSeed as a whole: there are moments of clarity, but they are few and far between.

[5]

Jack Davidson: I was very excited to see that we’d be covering this record for a Tone Glow issue as it’s one of the many auspicious-looking upcoming albums I’ve recently hoarded in my bloated Bandcamp wishlist. I’m not familiar with the works of either Mitchell or Harris, but the enticing cover collage and detailed description was more than enough to pique my interest. The hour-long affair unfolds in a series of highly orchestrated improvisations—there’s clear structure and form, but enough volatility to still sound spontaneous—of interplay between violin, trumpet, electronics, cello, percussion, theremin, flute, and voice. These latter two elements are the most prominent; several of the tracks, such as “Evernascence / Evanescence” and “Biotic Seeds,” consist only of spoken or sun lyrics and whimsical wind (or string) accompaniment.

Here, unfortunately, is where a shortcoming of EarthSeed becomes impossible to overlook: the vocal aspects of this album are noticeably weaker than the instrumentals. I found myself just waiting for whatever bizarre operatic vibrato or stage-play interaction was going on to be over more often that I actually enjoyed the singing or words, and for me the strongest parts of the record are when the music is entirely without them. However, it’s also the case that when I enjoy the vocals, the instrumentals just aren’t up to par—for example, on “Yes and Know,” which sabotages a delightfully manic ranting exchange with a completely uninteresting rhythmic backing. Any number of facets of EarthSeed on their own might make an enjoyable album for me, but all together it just sounds like a mess (and not the good kind).

[4]

Joshua Minsoo Kim: EarthSeed has a spiritual quality to it that’s more fulfilling when you let it surreptitiously wrap around you. As the album plays, I let its instrumentation and extended vocal techniques shape the space I’m in, each individual tone and squawk shaping me in the process. As the music presses up against my body, causing the occasional shiver, I recall Octavia E. Butler’s “Speech Sounds” and how in it, a disease has led to an inability for people to communicate with each other. On EarthSeed, I get this notion from Nicole Mitchell & Lisa E. Harris that the dystopian world we’re living in (or barreling towards) is also a result of miscommunication or, perhaps more accurately, a refusal and inability for people to actually listen to Black women. This is to say that EarthSeed’s title is very much purposeful: in the album is a seed for a new world, one that can only come from an outgrowth of hearing the stories of those often rejected power (the fact this was recorded in the Art Institute of Chicago is not lost on me). The words and music are both vaporous in their sonic qualities, but in them you can sense joy and playfulness, pain and curiosity, confidence and possibility.

[6]

Samuel McLemore: Yet more proof that the best modern jazz is that which doesn’t conceptualize the genre as a swinging dance music, but instead as an emotional journey, a “roller-coaster ride into the unknown.” Nicole Mitchell and Lisa E. Harris’s EarthSeed is one of the most ambitious and fully realized works the genre has seen in practically decades. A reimagining of classical chamber music using the techniques of jazz—or maybe it’s a restructuring of jazz through the vocabulary of modern composition? Earthseed manages to combine the cohesive emotional throughline of classic compositional forms (think of iconic program works like the Symphonie Fantastique) with the intense energy and stylistic freedom of jazz. This is made successful all by a group of incredibly wide-ranging and charming performers—vocalists Harris and countertenor Julian Otis deserve special mention, their duet on “Phallus and Chalice” is an album highlight, and Otis’s strikingly clear, operatic voice is one of the group’s real strengths, concretely setting apart this ensemble from any other in vocal jazz.

That I haven’t even touched on the textual component yet, or on EarthSeed’s inspiration from Octavia Butler’s science-fiction, is only testament to how richly considered and successfully executed this is as an album. Jazz and classical music have never been especially warm bedfellows, but works like EarthSeed prove that the connections between the two genres are closer than they would seem, and that this confluence is creatively fertile.

[7]

Average: [5.83]

Thiago Nassif - Mente (Gearbox, 2020)

Press Release info: Thiago Nassif is a Brazilian musician, composer and producer based in Rio de Janeiro, whose impactful mélange of pop, jarring no-wave, and edgy Tropicália has slowly been turning heads the world over.

Gearbox Records presents his latest album "Mente", co-produced by no wave icon Arto Lindsay, and representative, via its diverse list of accredited musicians, of the progressive, new-generational music scene that is bubbling away in Rio.

The album’s title is a Portuguese homonym meaning “mind” and “to lie”, and represents Thiago’s attitude towards what he calls the “post-truth” state of Brazil’s political regime. Mixing together the languages of Portuguese and English, Thiago goes deep into no-wave, experimental electronic music, Tropicalismo, jazz and rock, moving between funk carioca to dystopian, distorted bossa nova, and beyond.

You can purchase Mente on Bandcamp.

Jack Davidson: Back in my first year of college, I got the opportunity to cover an Arto Lindsay show for the studio radio organization (which for me just meant a free ticket) because the day it was announced I happened to be wearing my DNA sweatshirt. A few weeks later I wore the same sweatshirt to the concert, which got me an appreciative nod and smile from Lindsay on his way up to the stage. He then proceeded to play one of the best sets I’ve ever witnessed (I suppose I shouldn’t be surprised that two of my favorite concerts—Lindsay and Ikue Mori—have been DNA members). Standing at the front of the stage leaning into the mic, singing his delicate half-Portuguese/half-English lyrics with a baffling gentleness, hands blurring as they brutally wrack and wring a guitar’s ugliest notes into the soft grooving MPB of his backing band, the man’s terrifying ability to balance right on the razor-thin tightrope between conventionality and chaos was laid bare, and it was incredible.

Lindsay no doubt sees this same talent in the ideas and work of Thiago Nassif, whose two records both feature the guitarist on production and instrumentals. Nassif executes a similar mad-scientist merge of stylistic influences to create his unique sound, but instead of melding no wave skronk with Brazilian music, it’s the low-bit synths and sample loops of modern pop-electronica. The electronics play a variety of roles, from providing the main backbone of some tracks to injecting flavors of alien strangeness into the more straightforward full-band jams. Opener “Soar Estranho” was released as a single, but Nassif has a serious hit on his hands with “Plástico,” a track that demonstrates both excellent songwriting and alluring idiosyncrasies. There’s an ample supply of diversity as well, for after that song Nassif plunges into his own brand of hypnotic Tom Waits barroom shuffle for “Feral Fox,” gutter-pipe soul on “Trepa Trepa,” and whatever the hell you want to call what’s going on in “Cor.” And eclectic and well-crafted romp.

[7]

Sunik Kim: The distorted, thudding, somewhat ‘retro’ production on here initially grabbed my attention (“Soar Estranho”), but its heavy-handedness—from the incessant slapback delay on Nassif's vocals and the boxy filtering and saturation on the drums to the non-stop borderline-chiptune synth squeals—quickly became a tiresome distraction rather than a boon. The few moments of space and clarity stand out (“Feral Fox”), but are mostly still marred by unnecessary bit-crushed textural adornments.

Songs like “Trepa Trepa” reminded me of Sly and the Family Stone’s Fresh—but that album is amazing because of its minimal sound, one that lets the rhythms and songwriting speak for themselves. Mente, on the other hand, comes off as an odd nostalgia piece: on one level, it wants to force a ‘retro’ sound, a project usually doomed to shallow gimmickry; on another, it feels like Nassif and co-producer Arto Lindsay are attempting to emulate the sharp scritching of classic no-wave guitars with electronics (“Transparente”). The result is a bizarre middle ground: this album sounds expensive but cheap, a kind of hi-fi lo-fi, without enough standout songwriting to make up for the overproduced instrumentals.

[4]

Vanessa Ague: “Soar Estranho” explodes with electrifying energy, weaving plucky melodies and pulsating voice into one infectious groove. It’s the first track on Brazilian composer and producer Thiago Nassif’s Mente, and a captivating sign for what’s to come. As a whole, the album feels like a breath of fresh air: it’s seamless unification of retro sounds, funk beats, and lush tone painting make for a breezy listening experience.

“Plastico” bursts with an amalgamation of noise guitar, syncopated rhythm, and an upbeat chorus; “Cor” presents a fast-paced, distorted melody whose rising pulse is effortlessly compelling. But, sometimes, the atmosphere Nassif creates becomes monotonous due to similarity. “Trepa Trepa” and “Transparente,” for example, use similar techniques to what we’ve heard before on the album, but fail to provide anything new. He’s settled into a sound that’s engrossing almost all of the time, but really, the experimentalism of pieces like “Cor” is what makes them the most interesting to listen to. Mente shines most where it finds the balance between vigorous beats and gnarly melodies, providing fresh mixes of catchy rhythm and quirky refrains.

[7]

Jeff Brown: Mente is full of angular bit-crushed guitar sounds that share the sonic zip code of experimental guitarists like David Torn, Marc Ribot and Philip Charles Lithman. The music here is never purposelessly cold or harsh; as with the music of the aforementioned guitarists, this is a melding of acoustic and electric styles. Thiago Nassif’s crooning delivery is laid back, recalling early Yello albums, and it’s surrounded by rich grooves built from drum machines, sequencers clicking away with traditional Brazilian percussion (agogo, tamborim, conga), and trumpets: a delightful blurring of genres and instrumentation. The last piece, “Santa,” has upbeat Tropicália rhythms underneath its velcro fuzz and squelchy keyboards; with Mente, Nassif is continuing the legacy of hybrid Brazilian songwriting.

[7]

Leah B. Levinson: Recently, Joshua and I were speaking about no wave music. The question arose whether no wave can really apply to music today, even (or especially) if it sounds part and parcel with the music of the original movement. We discussed how no wave never really designated a codified style in the first place. No wave (which points to a loose group of mostly-white artists living and producing art with low overhead in downtown NYC in the late 70s) and Tropicália (which designates a small collective of Brazillian artists in the late 60s who rejected a looming dictatorship in their country) both had a sense of not just sound, but place, time, and political moment.

Tropicália epitomized the process of eclectic consumption, fusion, and poptimization that would later be anglicized by white artists such as Beck and Gorillaz. Tropicália found its power in an anti-colonial concept of consumption and global culture (borrowed from Oswald de Andrade’s “Manifesto Antropófago” or “Canibalist’s Manifesto”), a concept that its artists actualized by forging popular music that could function internationally yet remain specifically Brazillian, seizing for themselves Brazil’s representation on the global stage.

Mente not only exists outside of the context of the Tropicália movement that it apes, but suffers from what I perceive to be a certain scenelessness. Glossy synths, full-bodied drums, a nicely sleazy atmosphere, and kaleidoscopic beats and phrasing are delightful to be sure, but amount to a little less than promised. Nassif sponges up his surroundings and seeks to speak to a heavy political moment (Brazil is in the midst of yet another looming dictatorship) without offering direct solidarity or bolstering his voice with the voices and concerns of others.

While Mente succeeds as an alluring and accessible export which functions well on its own musical merits, I don’t feel completely satisfied. Being at a loss of an English lyric sheet, I hesitate to fully evaluate the album’s political effectiveness, but judging from a recent feature in The Wire I have a sense for what it presents.

Within the Wire feature, no specific policy is critiqued or political standpoint explored, more words are spent on Nassif’s relationship to—and inspiration from—visual art and architecture. While his forebear Caetano Veloso was arrested and exiled in his time and has published fiery op-eds in the New York Times speaking against his native country’s dictatorial right-wing government, Nassif is content to “not [shove] it in your face like a pamphlet.” He says instead, “it’s all hidden.”

Lately, I find myself more enamored by artists who have found aesthetic solutions to approximate agitprop by inventing work that is both enticing and effective. Recent examples for me include Moor Mother, Armand Hammer, Pink Siifu, and Matana Roberts, while older examples involve Crass, Ton Steine Scherben, Melvin Van Peebles, and Annette Peacock. Without a common global or even national stage, explicitly political works can seem to preach to the choir or offer little that is new to their audience, but I think there is a certain responsibility for work that parades itself as political to deliver on its conceit.

[6]

Raphael Helfand: Thiago Nassif is back with another sensuously skronky, genre-mashing album. His sound is distinctly Brazilian, but he draws from funk, no wave, psych rock and disco as much as he does from bossa nova or Tropicália. Distorted guitar and brown-note bass mesh with acoustic and automated percussion to form the rocky terrain for Nassif’s smooth Portuguese vocals, peppered with English phrases here and there, often drowned in robot effects or accompanied by background singers time-warped from the ’70s to add their deliciously dissonant harmonies to the mix.

Opener “Soar Estranho” features crunchy fuzz guitar from Arto Lindsay, who co-produced Mente and has championed Nassif’s work since he helped produce Lindsay’s 2017 Cuidado Madame. The track builds slowly, with Nassif monotoning over the mesmeric groove until the two-minute mark, when he suddenly goes falsetto and is joined on the mic by Gabriela Riley. They sing, “You left your number, you left your number / You left your number on my fiche / You left your number, you left your number / When you’re so out of reach.” The lyrics aren’t online yet, so I can’t confirm that Nassif actually rhymes “fiche” with “reach,” but if so, kudos.

The rest of the album ranges from slow, demented electro-bossas to panoramic island funk adventures to retrofuturist space grooves that recall the best elements of Guerilla Toss. Nassif changes direction organically, taking the time to let his songs build momentum. No matter how spastic his drumlines or jumpy his guitar licks, he never seems to be rushing. His unflappable cool pervades the album, culminating on “Transparente,” John Lennon’s wet dream of what “Come Together” would sound like if the Beatles were a better band.

Nassif’s vision never lets up. The quiet, disjointed dance groove of “Rijo Jórra Já” melts into “Santa,” the album’s eerie closer. “Santa’s” lyrics, poached from the notebooks of Nassif’s friend—the visual artist Fernanda Zerbini—describe a genderless saint who transcends the binaries of human society. The music feels transcendent too, pushing past western expectations of MPB and pop in general, existing in a nebulous space beyond the industry’s critical conventions.

[9]

Samuel McLemore: Though the press copy prominently displays producer Arto Lindsay’s endorsement of his songwriting skills, Thiago Nassif is certainly a better arranger than a composer. He probably wouldn’t even disagree with this assessment—such is the obvious pleasure he takes in letting the songs on Mente build up into inventive, immaculately produced arrangements. The production is the key to the album’s success here: each element of each track—afoxé percussion, squelchy synthetic bass, slashing guitars—gets its own place in the spatial field and its own tweak in the production process. This is as far from a lo-fi project as you can get, doubly impressive considering the credits note the album was recorded across multiple studios and the houses of several of his collaborators. Said fancy production isn’t just for its own sake: it’s a part of his compositional strategy because it allows him to accentuate small details and elevate them into key parts of his arrangements.

Despite the truly impressive production and my earnest love of Brazilian Afro-funk, Mente seems to shrink on each subsequent listen. Nassif’s overtures towards experimental and avant art forms strike me as mostly empty gestures not borne out by the relatively generic and boring music on offer here. What promised to be a fractured, no-wave, artsy take on Brazilian funk is mostly just well produced funk, always welcome, but nothing winds up being fulfilling. He seems to have mastered the art of the build up and the art of the little detail. Now Thiago Nassif just needs to learn how to craft a satisfying ending.

[4]

Joshua Minsoo Kim: The opening track told me all I needed to know: The skronk’s weak, the funk’s limp, the singing all too overlabored in its performative spontaneity. The problem with an album like this is that it’s forever halfway to something decent, unable to commit to a single idea for long enough to satiate the urges its musical smörgåsbord creates. The Arto Lindsay co-sign and production credits make sense but all it does is bring me back to MPB star Marisa Monte and how her music—whether effortlessly pretty or featuring John Zorn—was still undergirded by memorable toplines. Mente falls into a familiar avant-pop trap: It never sells me on its pop or experimental tendencies.

[3]

Shy Thompson: I was really into LEGO growing up. My mom really appreciated that it wasn’t difficult or expensive to keep me entertained until I started getting into video games. I had a big container of LEGO blocks, and I was happy as long it was topped up every so often with updated blocks. I never fancied myself a particularly creative person so I thought I just liked the act of building, but realized what I actually liked about playing with LEGO during a brief stint with them in my early adulthood. Having decided that the basic blocks were probably too childish for my beefed-up and more wrinkled adult brain, I figured a LEGO replica kit of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater was more appropriate. I pushed through my boredom to build the thing, and fought against every temptation I had to ignore the instructions and put it together completely wrong.

I had taken a roundabout way to learning what I had already realized as a kid about 8 years previous: I want possibilities. There’s only one “correct” way to build Fallingwater; you end up not appreciating every block for what it can do, but what it will do. Even more than affording me creative agency, what I loved about LEGO is that every block is a work of art unto itself; a conduit for potential. I’ll take the block that’s 1 space wide and 5 spaces long over a completed Fallingwater any day, even if those kits go for hundreds of dollars on eBay now.

Thiago Nassif’s Mente is, to me, the miniature LEGO version of a Frank Lloyd Wright masterpiece. There are elements of things I love in this album—Brazilian funk, industrial no-wave stylings, extremely cool instrumental choices, and fun straight-ahead pop melodies—but none of it is arranged into something I love as a completed build. I love the funky driving rhythm of “Pele De Leopardo,” but nothing else about it; I love the strange sounds in “Vóz Única Foto Sem Calçinha” that remind me of a firework whizzing into the sky and exploding into a distant flash, but not much else; I love so many of the little moments that come in and out of focus on “Plástico,” but I don’t love it as a song. I like “Santa” the most as a fully realized track, but it comes too late—the album’s already over. I see what Arto Lindsay sees in Thiago Nassif, and why he wanted to mentor and produce for him. There is a lot of good here, and that’s what makes Mente so frustrating for me; it only feels good in short bursts. The building blocks for something great are all here, and I can’t deny that they’re put together well, but they’re not put together creatively. Tear it down and build it a different way, and there might be an album I like in this tub of LEGO bricks.

[4]