Tone Glow 016.5: Sasu Ripatti

An interview with drummer and producer Sasu Ripatti + a mix for a special midweek issue

Sasu Ripatti

Sasu Ripatti is a Finnish drummer and producer who’s created house, techno, and other electronic musics under various names, most popular of which are Luomo and Vladislav Delay. Earlier this year, he released remasters of his albums Vocalcity and Multila. He also released Rakka, his first solo album in more than half a decade. Later this year, Ripatti will be releasing a collaborative album that he made with Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare. Joshua Minsoo Kim and Sasu Ripatti talked on the phone on May 6th, discussing veganism, his family, his new albums, and hiking in the arctic. Photos by Antye Greie-Ripatti.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Hey, how are you doing?

Sasu Ripatti: I’m doing alright, I’m doing alright.

Sorry for pushing the interview back a little bit, I had to bring some food to my sister.

No problem at all. I’m just back in the studio. My wife [Antye Greie-Ripatti aka AGF] is into Westworld—she wanted to see an episode. I’m trying but I’m not really into it.

What’s the appeal of Westworld for her?

She’s very much into futuristic stuff, but I think she’s getting annoyed by the militarization presented in the show. She does a lot of experimental, intellectual and demanding art so maybe she just wants to balance that stuff out; it’s just entertainment. I didn’t see the first two seasons—I’ve only been watching a few episodes—so I’m not really getting it. She watched it all the way through, though, so maybe she’s just seeing where it goes.

Do you two usually watch TV shows together?

No, I don’t really watch TV much at all. We don’t have TV, we have those…

Subscription services?

Yeah, but I hardly watch anything. We have a 14-year-old daughter so sometimes we watch movies, but I’m not really a fan of TV shows.

I’m the same way. I know couples usually bond by watching TV shows together, but that sort of thing is hard for me because I’m really not into TV.

Years ago when The Wire came out we both went deep into that, but that’s already quite a long time ago now. I guess she’d enjoy the notion of us sharing that but, eh, we share a lot of other stuff.

I wanted to ask, before anything, a question that someone had suggested. Do you have a traditional Finnish food that you like the most?

I’m something of a foodie but I’m also mainly a raw food vegan. Traditional Finnish food is a lot of meat and carbs—it’s really Russian influenced. Traditionally, back when it was about survival, it would just be roots, like potatoes with meat or fish and not much spices. There’s not much that speaks to me but there’s this Nordic cuisine—New Nordic cuisine, you’d call it—like Noma and all those restaurants where they put wild herbs and find lots of stuff that’s both tasty and healthy. There’s no dish though, it’s all freestyle. I can’t really put a dish out there that I really like in terms of traditional Finnish cuisine.

What’s a go-to meal that you typically prepare?

It’s pretty freaky stuff (laughter). We live on an island in the Baltic Sea close to the Arctic Circle. There’s really not much going on—there’s no shops—so the availability of foodstuff is very limited. I eat lots of fats from seeds and nuts, and grow lots of sprouts and microgreens. There’s canned foods like sardines if I can get them. It’s usually a combination of fats and vegetables when I can find them.

I lived an unhealthy life for quite a long time: traveling and not sleeping, doing too many drugs and drinking—all that stuff. It came to a point that I really had to do a U-turn—this was a while ago—and I’m quite healthy these days.

And I’m sure it’s a great feeling! I’m sure you’re feeling better too.

Yeah, yeah. And I have a daughter so I have to be a good example, or try to be one.

Are you not super strict about being a vegan? You mentioned sardines.

Yeah, I’m not super strict at all. I’m not a vegan for ethical reasons—I mean, I’m ethically concerned, but I eat so little. I’m not against killing animals per se. If I could kill the animal myself I’d feel okay, but I’m not into slaughterhouses—that’s just pure madness. I don’t eat meat, though. I haven’t eaten meat besides fish for maybe 25 years. I’m a longtime vegetarian. I used to be more of a raw vegan for maybe ten years but I started to get so skinny that I felt like I needed to get more animal fat.

When I was touring with Sly Dunbar he would carry sardines with him. I thought it was disgusting, but I pushed myself to eat it and now once a week—or every two weeks—I eat a can of sardines just to get those omega fats. But I hardly ever eat fish, and I never eat farmed fish. I’m really put off by the industry. I used to catch my own fish and eat it, but I kind of left that all behind.

So what are the main reasons for being a vegetarian or vegan? Is it mainly just because of the industries?

It’s about health, also. But I never really liked meat. I remember even in my childhood I would be disgusted by meat, so I stopped eating it when I was 16 or 17 when I left home. When I started making my own food I couldn’t stand it. It’s been a long time since I’ve eaten it—I’m 43 now.

I wanted to ask about you being a father. I know you’ve talked about this a lot, how you moved from Berlin to Finland in an isolated area to raise your daughter. Were you ever scared about the prospect of raising a child? I’m not sure if I ever want kids, but I know that part of the reason is that I’d be scared about my own ability to raise someone at a level I’d be happy with.

For me it was kind of a freaky prospect.

How so?

Because it’s a huge responsibility, and there’s also the fear of losing freedom. For a long time I couldn’t imagine having a kid, and now I can’t even remember what my goals in life were—or what made sense—before I had a child. It put things into balance.

I didn’t have a good childhood. I had an alcoholic father—he was quite old. I didn’t really have much family stuff to speak of, so for me it’s about correcting something in this weird, secondary way. I really wanted to give something good—something I wasn’t given—and I really wanted to do a good job with that. I didn’t really plan for it much beforehand, but when it happened I was ready and I knew I’d take it really seriously. It’s one of the things I decided to do properly—if there’s one thing I wanted to do in this life properly, it was gonna be doing this. But of course, now my daughter is 14 and at this point you have to let go.

I guess I was always worried how much time it’d take up, that there wouldn’t be time for other things. I used to live a hedonistic life, being really out of it, doing exactly what I wanted. I was afraid of having to stop that, and it was actually a lot of work to stop it, but it wasn’t a good way to live life. It’s a good thing to experience but you burn out. I almost died, I had to get myself together.

How’d you almost die?

My heart stopped working, I needed a big surgery. I’m an intense person—whatever I do, I do full-on. And I did that stuff pretty full-on but I ignored all the signs and kept going, and it came to a point where I had to stop. It was a lot of work to get myself back to normal. And, well, here we are.

I’m glad that you’re here, I’m glad you’re alive. Were there people who were helping you get through this, to move away from that lifestyle? Was Antye instrumental in that?

I’m quite stubborn, so I didn’t really take any help, and I didn’t go to any therapy. I guess I always felt like you had to clean your own mess. If you’re in a relationship and going through that, it’s really not nice for the other person—it’s collateral damage in a way, you know? Antye was a big support, though, and it’s part of the reason that we’re still together—it’s been 20 years now that we’ve been together. It brought us closer.

You mentioned that your father wasn’t the best role model. A lot of times, when people decide to have kids, part of the process involves unlearning specific behaviors your parents had so that your children are happier than you were. Was there anything that you felt had to be unlearned in order to raise your daughter in the best possible way?

It’s hard. And annoying. Even though you’re aware of it and happen to repeat the habits your parents had—both good and bad—it can be really difficult to deal with. I guess I believe quite strongly in progress. I think the way the world gets better, at least in theory, is when we do better—and do more—than with what we were given. It’s not an excuse to be an asshole if you were treated badly—I mean, sometimes it’s unavoidable. (sigh). I don’t really understand. Some of the people who come from the worst war zones and have been in horrible situations are the most positive ones.

Anyway, I was happy to offer more than what I was given. What I said—“Give more than you were given”—is a nice motto to live by. I had to put my ego aside. It’s a nice change in life when you’ve lived a long time doing exactly what your ego wants and asks. My mother is still alive and we have a strong connection, but my parents were both artists. So while I didn’t get the average middle class family life—no dinners together and a pretty messed-up everything—I was really influenced creatively from the very beginning, and felt supported creatively. It’s give and take; I wouldn’t change my life for a normal one.

That’s a good way to look at life, to see what’s happened and do what you can but to also try and think positively.

Yeah, what can you do, right? There’s so many things you can influence and change, but there’s a lot you just have to deal with and you have to make the best of it. There’s good stuff also in my upbringing. I don’t think I’d be doing what I’ve been doing if I didn’t feel supported as a kid, but also if I didn’t feel I needed an outlet for dealing with things.

I know your parents were writers, what sort of stuff did they write?

My father wrote novels but he was also a critic and he wrote some famous theater pieces. My mother wasn’t a practicing artist but she was supporting work for artists in a government position—she was the head of a regional arts council. She did release several poems afterwards, though.

What are their names?

My father is Aku-Kimmo Ripatti and my mother is Maija Kotilainen. Also my grandmother from my father’s side was a famous literary rebel. She started the Tulenkantajat group back in the early days. Her name is Iris Uurto.

You said your daughter’s a teenager right now and that you’ve been letting go a bit. What’s something about your daughter that’s inspired you?

I guess if someone comes from you, there’s part of you in there but it’s also a whole different being, you know? The kids today are so smart. When I compare them to myself at that age, I was fucking out of it, I didn’t have a clue. She’s traveled with us around the world and with the internet there’s a lot of curiosity. She reads a lot. Her knowledge is just insane, it’s admirable. Overall, it’s just how she’s turning into her own person, dealing with her own stuff. I guess there are small things that have stood out more than just one big thing.

Can you give an example of a small thing that made you go, like, “Wow, this is my daughter.”

Just a few days ago we were doing a feature for The Wire magazine, do you know them?

Yeah! I write for them.

Okay, yeah. So we were doing, like, a double Invisible Jukebox feature with me and my wife together. Our daughter took the photos for us and she was really gracious behind the camera. She’s 14 so I wasn’t sure how she was gonna handle it but it was great. I wasn’t sure if The Wire was going to do it, but they were totally into it and hired her to do the feature.

That’s amazing.

Yeah. And I recently released this solo album, Rakka, and she did the artwork for that also. She’s been writing a lot of stuff already too. Seeing the creative sparks is wonderful.

That’s so awesome. You were raised by two artists and she’s now being raised by two artists, so who knows what she’s gonna do with her life.

Yeah, but I’m pretty sure she’s not gonna do anything with music.

Is she mostly doing writing?

Writing and films. Music is too boring with both parents just nonstop going about it. It’s like, “Give me something else!” But hey—what is this interview gonna be about? I think the guys from distribution [Forced Exposure] said this was gonna be about the Sly & Robbie album [500-Push-Up], but we’re talking about family (laughs).

Oh yeah we’ll get to that. My whole philosophy is, well—I’ve read a lot of interviews, and I feel like you can talk about the music and the process behind it, but behind every artist is a human being. And getting to know them on that level helps to reveal stuff about the art that wouldn’t be obvious otherwise.

Yeah, yeah. I’m totally into this. This is some personal stuff we’re talking about and I’m sometimes not clever enough to not say the things I shouldn’t say. For example, my wife will read an interview I’ve done and she’ll say, “Oh God.” (laughter). But yeah, I’m getting so bored of those stock questions, you know? I asked that because I just wanted to clarify.

No worries, it’s happened before. Usually interviews don’t go so far into talking about personal stuff like this.

No, they don’t. So what’s your plan with this interview? Is the Sly & Robbie album going to be part of it?

Yeah! I’m going to go into questions about your music now but I did want to ask about your personal life first because I think it’s interesting.

Yeah, and I can talk more about it. It was just that I only now realized what was happening. We can go back to personal stuff, no problem.

I’m a high school teacher and the thing I’ve learned the most is that if I focus too much on only teaching content, if I only care about them understanding science—I teach science—then they’re not gonna learn it in the best possible way. I spend some time in my classes just talking about their lives, about topics they care about like racism, about personal stuff like dealing with shame and having healthy relationships.

That’s super essential stuff. And I think kids nowadays don’t really talk about stuff like this at home. I think it’s super great to get them to talk about that stuff—or to even listen—but if you can get them to share their thoughts, that’s super great.

Yeah, it gets pretty emotional at times. For a lot of students, school isn’t always a place where they can comfortably express things and themselves, especially in a science classroom. Usually if they’re expressing themselves it’s in an English class or an art class. So I try to make it a space where they can be comfortable, where they know that we can grow together. And that can only happen if we break down these walls, if we understand that the things we learn in my class go beyond just learning science, that it’s about understanding that failure is okay—it’s about working together and encouraging each other. All that only comes from understanding each other on a personal level. I try to carry that philosophy with me in my interviews.

Yeah, it’s admirable. It’s good stuff.

I’m not sure if you ever talked about it in an interview before, but when did you first meet your wife?

Around 2000. She came up after a show and said hi—she told me that she came to see my concert.

When did you two start dating?

It was kind of right after.

You two clicked right away?

Yeah, but she was married, so it was difficult. And there’s the age difference. But we connected right away.

You both create different types of music. What’s something that you feel she does well that you can’t do?

Are you asking specifically about music?

It can be about music, or even about raising your daughter, or as a person in general. What are some differences between you two and what qualities does she have that you really admire?

She’s fearless. She’s not afraid to fail. I think it’s because she was raised in the GDR, in East Germany. It was a non-individualistic communistic system that built good people, in a way—there wasn’t much of this capitalistic, superficial stuff there. I’m a perfectionist and I want to do things proper or not do it at all, but she’s not afraid to try and fail, even in front of people. She always tries new things.

She’s not afraid to put personal stuff in music—I’d feel uncomfortable doing that. Nowadays, she’s doing a lot of political work—music and otherwise—and putting her own opinions in there, raising uncomfortable issues about race and gender. I admire that. I don’t have the balls to do that.

I was raised on mostly instrumental jazz music so horn lines or a walking bass or whatever would tell the stories. I’m not used to pointing things out in such a raw way, presenting it as it is. It takes a strong person to do that, to put it on the table—especially if you’re a woman. She’s not afraid to do that. To travel and present those ideas… it takes guts. I guess I always just want to hide behind layers and layers (laughter).

You mentioned jazz, and I know you were primarily influenced by it. When I listen to your albums—any of them, from throughout your career—there are unpredictable patterns that ensure you don’t get bored, but still keep you firmly within a specific atmosphere. I guess that’s what I’ve always felt was the link between your music and jazz. And I’d say that’s also true of a lot of dub music. So, to turn this into a question—sorry, I’m just talking about how much I like your work (laughs).

No, it’s okay.

When you perform live, do you have a setup that allows for that improvisational element, or would you say things are more curated and you have specific things that you generally want to make sure happen? And has that changed throughout your career?

It’s definitely the former for sure. I get easily bored and frustrated and make drastic, stupid reactions. I learned long ago that I should avoid that but… you know, it’s still music, right? I deeply hate—let’s not say hate—but I deeply dislike predictable music. For me, even if an audience is hearing something for the first time and it could be unpredictable for them, there’d be no surprise for me and I would just be doing some stupid playback thing. I don’t know. Life is too short for that, and I’m not made for that at all.

I’ve of course tried new things throughout the years, but I always try to maximize the amount of unpredictableness and randomness and improvisation. I try to push myself outside my comfort zone, and oftentimes don’t know what’s going on myself and have to problem solve in real time. It’s not a comfortable situation to be in but it makes musical sense—it challenges me to react in the moment. Sometimes I fail, of course, but that’s more interesting than knowing what’s going to happen. I just don’t understand that mentality in music; I hate predictable music. Okay, I said hate again—I have really strong feelings about knowing what’s gonna happen four bars ahead. I’m not built for that.

Did you seek out unpredictable music when you were younger?

Maybe. I have a background in death metal and grindcore—really hardcore music. I don’t know if it’s predictable or not, but it’s at least quite extreme. But when I was young and naive and didn’t know better, I thought Red Hot Chili Peppers were cool. You know, you have to start somewhere, and then new doors open. No regrets.

I don’t only listen to experimental, weird, extreme, unpredictable music—no. But I picked up jazz when I was young and found my home there and never really left it. I was 14 or something.

Did you have a specific jazz musician or album that really blew you away when you were younger? Does anything come to mind immediately?

It’s really cliché but Miles Davis’s Sketches of Spain was something my father had. I remember that I didn’t really understand what was going on because I was so young. And then around 14, Kind of Blue was kind of a pop, easy jazz album, but it really opened me up to that modal style. I found some Coltrane stuff and was listening for drumming but didn’t understand what was going on. I had to go into that ambient mode, where it goes into the background. I felt really good in there, I didn’t feel like I had to use my brain to figure out what the fuck was going on (laughter). These answers are so cliché.

I mean, that’s fine.

But I guess that’s also why Kind of Blue is so popular.

Is there a reason you specifically went and made electronic music?

I wanted to be a jazz drummer, that was my goal in life. I went to New York with my mom when I was quite young—I think my mother had some work trip and took me along. This was when I was getting properly interested in jazz and there was this drummers collective and we went to Blue Note. I realized that there wasn’t really jazz anymore. I’d been listening to these old jazz records and I was somehow stuck in the ’50s and ’60s—the bubble just completely burst. It just wasn’t possible to become the jazz drummer I wanted to be. There are drummers now, like Brian Blade and Kenny Washington, but they have to hustle as much as they can. Jazz doesn’t really exist anymore in the way it used to.

It definitely doesn’t have the cultural cachet that it used to have.

The culture has changed, the world has changed, everything has changed. Anyways, I was never interested in electronic music. I started making music with electronic gear before I even heard any electronic music. It was just a chance for musical exploration on my own, without having to negotiate with five other guys about stuff, you know? You don’t have to please anyone. I guess I have a producer mindstate and have ideas for how the music should be.

I came from a small town and it was just people with guitars, so a whole new door was opened when I got some gear to play with. Just the idea that you could be by yourself and make music was great. Of course, it’s good to collaborate and work with others so you don’t go on ego trips, but the possibility of making music with machines without any restrictions is a nice idea if nothing else.

You said in a previous feature that you think Vocalcity is the worst Luomo album. Is that because you think it sounds too predictable?

Yeah, it sounds pretty naive. In hindsight, it was something I just wanted to try for a while and I couldn’t give it up. I was insistent that I wanted to explore this vocal pop thing and push it as far as I could. I exhausted my options and then I had nothing else to say about it. I don’t think about it too much, it was just something I wanted to do—and for a while I had fun doing it—but I don’t really have an opinion on it anymore. I know we released Vocalcity for its 20th anniversary. I went through the tracks again for the remaster and, while there’s something good in them, it’s not… I like The Present Lover most.

At the time of the feature you said Convivial was the best and that The Present Lover was second best.

Really?

Yeah. What do you think you did on The Present Lover that succeeded so well? How did you build on the ideas that were present on Vocalcity?

I never really cared for house music and never planned to make any of it. I just wanted to make experimental pop stuff. The house beats were a medium—a carrier, if you will—to hold the hooks. I think The Present Lover has the best hooks. I mean, it sounds really old and the limitations of the gear are quite audible, but… did I say Convivial? There are good hooks in other Luomo albums but I thought The Present Lover was quite ambitious.

I was still doing, like, “heroin house” and ambient stuff. This Luomo thing just happened and it confused people, but I thought it was brave of me to fully go with that pop stuff back in the day. I wasn’t really thinking about all this—I was never savvy enough to do the “right” thing. I ruined so many chances by doing whatever I wanted instead of calculating the right moves, but back then I was full-on passionate about doing hooky, poppy stuff. The Present Lover probably didn’t satisfy a lot of Vocalcity fans or Chain Reaction fans but I didn’t think about that stuff at all. And looking back, I guess that was a good thing to do. I admire people who take risks, like Miles Davis or Coltrane, or even Bob Dylan.

Like with Miles Davis, he could’ve played ballads forever but moved on. With Coltrane, even after A Love Supreme, he moved on. That always spoke strongly to me, this idea that there’s this path onwards where you don’t really know what it’ll look like. It’s about exploration, and I think The Present Lover was kind of like that. I have good memories about it but I haven’t listened to it in so many years. There’s this track I did with Antye, “Talk in a Danger.” I think the production failed but it’s still one of the experimental pop things where I succeeded most.

How do you feel about fans caring about albums you’re not particularly interested in? Most people typically say they like Vocalcity the most—does that affect you at all?

Well I mean, first of all, it’s a free world (laughter). I don’t have social media, and I’ve been away from the public for so long and haven’t released music that I don’t think there are many fans. There are people who may know my stuff from the past but I don’t really think of my fans at all. If there’s somebody who likes my music then that’s great, but I don’t really have a problem with what they like.

When I was young I was listening to Tricky and Massive Attack. I really liked Protection and Maxinquaye, but I was really disappointed by the albums they released afterwards. And they probably liked it more, or at least were giving their best and wanted to do something different, but it didn’t match with my idea of them. It’s the same thing. If somebody found something in Vocalcity then who am I to say anything? I can’t get stuck there and let fans decide what I do. It wouldn’t be acceptable. To each his own, right?

Right. You said that with raising your daughter, your whole mentality was that you wanted to give more than you were given and set your ego aside. Do you feel like that mentality is present at all in your own music? I feel like you have to set your ego aside to go out and make different types of works.

I’m not really sure I agree with that. I think it’s really egoistic stuff to make music alone. And you really get easily lost in yourself, your head is up your you know where and you don’t see the forest for the trees. You can go months on end in the studio and think everything is fucking great. One of the reasons I try to play some concerts is that I’ll try unreleased stuff so I can have a reality check. And I’ll play songs for Antye too. It changes perspective enormously when somebody else is in the room—there’s no stroking your ego there.

I hope there’s some maturity there too, that I’m no longer 20 in my head, that I’m more well-rounded without getting too boring and established or playing things safe—that’s a big fear.

Do you think it’s important to put your ego aside, or do you think there’s some benefit to leaning into it?

Maybe not in the long run. You might get lucky but it’s not something you can do forever. I really work hard on trying to progress with my own craft and at some point, you have to realize that you’re not gonna get much shit done, no matter how much you want.

Every little step forward is actually a great thing—that’s something humbling that I’ve had to learn again and again, and I’ve learned more and more throughout the last five years or so. I took a long break from music and only really worked on my own to rehearse and practice. It’s a humbling thing, your ego gets crushed (laughter), but from there you can produce from a more humble point of view. Maybe it also just has to do with getting older, more mature—or at least I hope so.

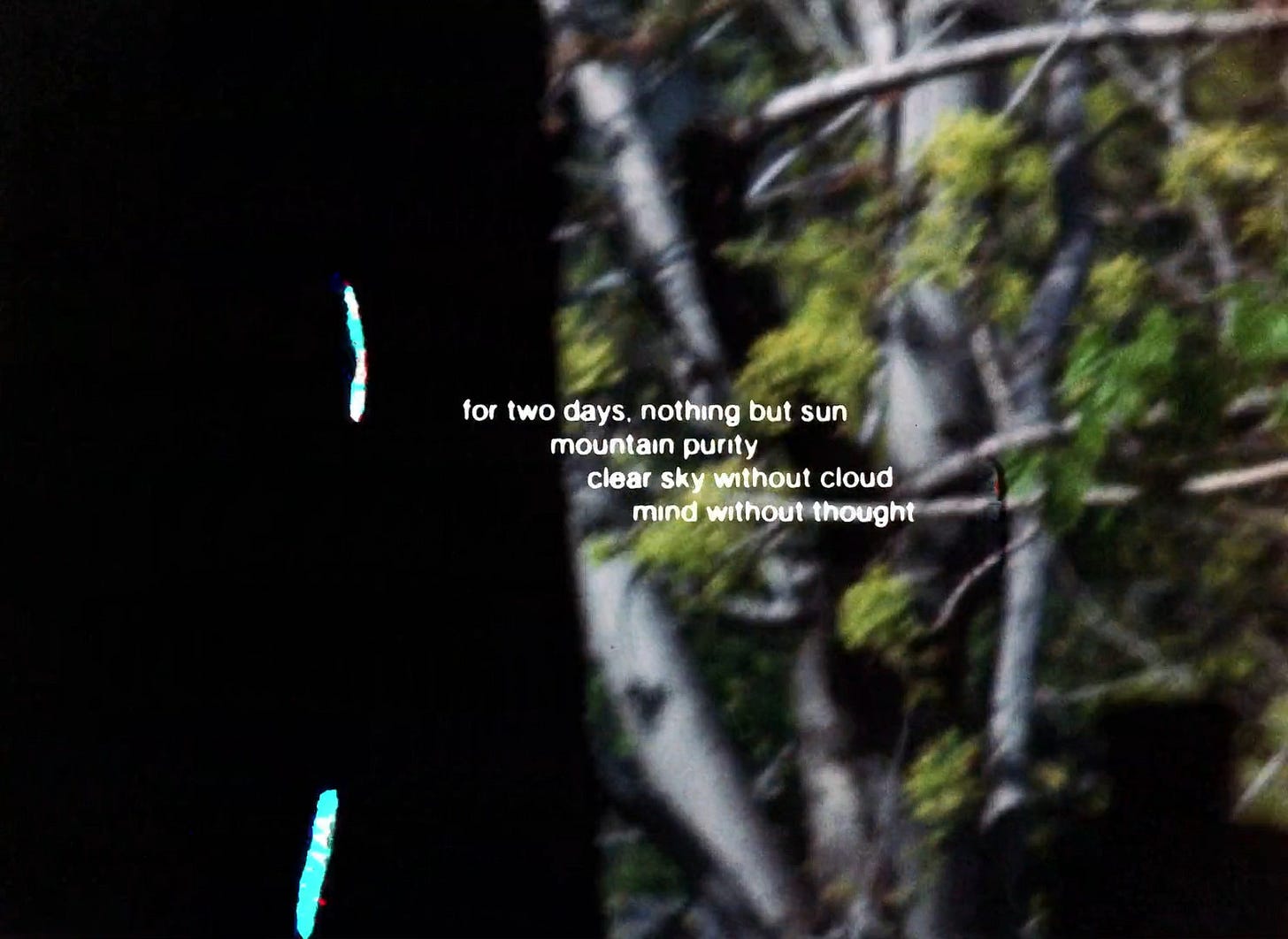

For Rakka you said you were inspired by hikes you had in the arctic wilderness. What’s something someone wouldn’t expect about hiking there?

There’s a good chance you’ll die if you make a little mistake. It’s a life and death situation, and it’s very much about survival—you would not go there unprepared.

How did you prepare?

I started doing hikes ten years ago and didn’t start at hardcore places. It was a gradual progression: you learn how high up in the mountains you can go, how much you can carry, whether you can go to places with no GPS or phone signal—all kinds of stuff. You learn to face your own limits and fears. When you spend a week there, you don’t say a word and you don’t hear a word. I never see any humans—there’s maybe some animals.

For me, it’s a silent retreat—it’s really a rest. If you have issues with yourself they certainly come to the surface (laughter). But I’m a happy camper there, even in sub-zero degrees and the shittiest, most miserable conditions; it’s purifying and cleansing, you really become close with yourself and reality and your own feelings.

It’s also inspiring. I get my best ideas there. I almost exclusively hike above the tree line and the feeling of space is so vast—you can see tens of kilometers in every direction—and there’s no roof or walls. It’s unlimited space.

I’m trying to figure out why hiking there leads to that—like, the ideas are flowing, like literally flowing. The creativity is bursting and I keep writing those ideas down and come to the studio. We live in a remote area, so for the average person it would be considered out in the middle of nowhere, really esoteric and quiet and all. But when I come to my studio, I don’t feel the same way I do when I’m hiking. Even though I have a big window that looks out into the forest, I still feel confined. It’s a little puzzling how the hell it’s such a big difference when you’re there in the open space.

Like I said earlier on, when I do something I do it full-on. This hiking thing… I hope I don’t die, but it’s definitely pushing boundaries and limits. Overall, as long as you’re realistic and honest with yourself, you can push boundaries and that’s how you grow and get good results out of different things. I hike every summer as much as I can. It’s like putting money in the bank, for real. There’s a big interest rate, it always comes back one way or another.

What sort of ideas have come to you? What does that look like?

It’s like the floodgates are open. I learned that I’ll get ideas and be overwhelmed trying to write it all down so now I’m just like “fuck it”—things come and go, and I just enjoy all the thoughts and ideas as they come. It might be something I’m struggling with work-wise or some detailed issue in the studio, and I’ll think, “Maybe if I just did it like this instead of that.” It can be small things that, for whatever reason, I didn’t have the perspective for in the studio.

It could be big things too. Like, “Why am I here? What am I doing?” It’s anything in between. There’s so much time when you walk hours and hours, things just come up and start flowing, and it’s really good to let that all come. Sometimes I’ll write lyrics or track titles, like when it’s evening and you’re in the tent. Nowadays I’ll bring my Kindle and read in my tent at night.

What sort of stuff are you reading now?

I’m reading tons of stuff, all kinds of stuff. Books about yoga and music and coffee and tea and fiction. I recently read Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem. Have you read that?

I have not.

I’m not really a fan of sci-fi but that was fantastic. I read so much, I’m a book whore. But I’m not really good at keeping track of names. It’s a little ignorant, even, how I read. I’ll have read something and if you ask me who the author is, half the time I won’t know. I decided I don’t care—I’m not gonna be a fanboy. I’m already fanboying about so many things—producers and what they’ve worked on and what gear they use, there’s coffee this and tea that. Books? Just let me read them and enjoy them. But I mean, I could recognize Murakami’s writing, for example.

Rakka is a lot noisier than your previous Vladislav Delay releases. Do you feel like you wouldn’t have been able to make this if you hadn’t taken a break from releasing solo music?

I only hope I’d have anyway gone forward, but certainly the break helped me gather strength and gain a bit of distant perspective on my productions. Maybe mostly the break helped in that I could spend a long time just working on music without even thinking of releasing anything, just looking at where it could go—trying new ideas and techniques, directions and all.

I guess we should finally talk about 500-Push-Up?

(laughs). Yeah.

What’s the meaning behind the title?

Are you gonna talk to Sly?

I am, did he pick the title?

Let Sly explain it to you. He’s the man with 500 push ups.

I know the album is from jam sessions you had with Sly & Robbie. I’m sure you were a fan of their music before that all happened, so what was it like finally working with them?

I worked with them long before these sessions in Kingston. At least five years prior we worked both in the studio and live, so we got to know each other quite well—I wouldn’t have gone to Kingston otherwise. Robbie was into the idea of us doing a trio recording.

Kingston is Kingston, it’s not northern Finland. Things work very differently there, so it was an adjustment—just how long things take and stuff like that, it’s a different culture. It was great, though. I brought a bunch of cymbals and percussion with me and asked Sly to play some unusual sounds and I would also try to get him to play a little differently and he was into it.

The idea was to just play bass and drums—to play unusual rhythms—and then come home and see how I could construct the music. I wanted it to just be bass and drums but it ended up being different than I had initially envisioned—there’s more noise and stuff. I just tried to go with my instinct.

You said that you asked them to play differently. Do you feel that working with Sly & Robbie forced you to approach the music differently as well?

I had never done something like this before and had to find a way to do it, but after the recordings it more or less became a solo project. I wasn’t thinking about what Sly & Robbie would think—they totally just gave me their blessing to do whatever. It’s funny, I think you should know that we’ve known each other for a long time—I would say we’re close and have worked a lot together—but they don’t really know my solo stuff at all. I never played them any of my stuff. It’s interesting. My wife was like, “Are you crazy? Why don’t you just play them your stuff?” And in my mind it’s like, whatever, it doesn’t matter (laughter).

It’s interesting that they don’t know it. I don’t think they know my artist name at all. I remember we were touring in Japan and they were doing an interview and the interviewer asked them, “So, how has it been working with Vladislav Delay?” and they were both like, “Huh? Who’s that?” (laughter). But I really love this Jamaican mentality and attitude. As hardcore and difficult a place it may be, it builds up some of the most beautiful people I know.

I’ve always been a fan of Jamaican culture—I went there when I was 16 or 17 for about a month. I really fell in love with Jamaica then. I got along with people there, it felt like home, it felt really easy for me. Sly & Robbie know my real first name but they call me stuff like, I don’t know, whatever—they call me “Ice Man.” You know, Jamaicans always have nicknames. I think Sly often called me Tubbys—it was Little Tubbys for a while. All kinds of stuff (laughter).

But yeah, I don’t think they know my stuff. They’d be a little shocked to hear Rakka to be honest. When I don’t see them in person, it’s hard for me to talk with them on the phone. Like with Sly, when I talk with him on the phone and there’s a bad connection, I don’t understand what he’s saying half the time.

I was actually worried about that for my interview with him.

Do you speak patois?

No, I don’t.

Oh, you’re going to be so fucked (laughter). But he’ll treat you nice. When he gets excited and is talking, I really just don’t understand. And when they’re in Jamaica talking between themselves, understanding half of what they’re saying diminishes to understanding maybe ten percent. It’s so beautiful but I don’t have a clue what the fuck’s going on (laughter).

Robbie Shakespeare, Sasu Ripatti, and Sly Dunbar

Can you share a memory that you have of Jamaica, of being with them? It doesn’t have to be music-related either.

Sly knows this great place to eat. I can’t remember the name but it’s like some hipster food place with some raw vegan pizza. But to be honest, I don’t like Kingston too much. Especially nowadays, it’s so Americanized and busy, there are so many cars and the traffic jams are bad—the infrastructure just can’t handle it. My favorite moment from Jamaica was being in the studio but aside from that, it was being in the southern part of Portland. I’m still waiting for Sly to buy me a house there—he promised, I don’t know what happened (laughter). You can ask him where my hut is in Portland. I’m planning to move there, it’s my home. I think I lived there in my past life.

What was memorable about Portland?

I love all the green, there’s just a million shades of green—the jungle. It’s a simple life, it’s really beautiful. Sly wouldn’t want to go there, he’s a total city boy, he loves Kingston. Robbie too. He lives in Miami now but if he goes to Jamaica, he goes to Kingston. It’s too normal for them. Grace Jones goes to Portland though, she likes to be there—she has a studio there. She was there the same time I was there.

Did you meet her?

No, but Robbie’s in touch with her. We actually had plans to get Grace Jones on the album but it started taking forever and I didn’t wanna wait any longer and Robbie was like (in Robbie’s voice) “Yah mon, yah mon” (laughter). I heard them talking on the phone about it. It could have been nice.

Were there any dub albums you were listening to while making 500-Push-Up? Is there something specific about dub that appeals to you that you were trying to capture with the album?

I wasn’t listening to any dub or related music. I guess if anything, I was trying to be conscious and not make a dub album, or at least stay away from dub clichés. For example, I decided not to use any dub delays or similar traditional things, but of course the foundation of drums and bass already give it that dub feel. It’s that flow of bass and drums that’s the interesting thing: it's such a strong foundation that it allows for plenty of experimentation to take place over it—it carries it all forward. Overall, dub has a certain explorative idea about it that I find very interesting, but it’s almost sacred as well. I have always been quite reluctant to put my fingers on the dub pot, actually.

What plans do you have next, be they music-related or not? Do you think you’ll take another break from music or are you itching to make more?

I’ve been very productive for a while now. It’s again been mostly explorative and about learning—not sure how much of it will ever see the light of day and be published, but I’ve felt more inspired than I have in ages. I was supposed to be traveling quite a lot this year for shows and now everything is cancelled until next year, so I’m trying to figure out how to get by and survive. But also, I have a whole summer ahead—there’ll be lots of hiking for sure.

Sasu Ripatti has just launched a Bandcamp subscription. Of it, he says the following:

I'm going to offer exclusive material to subscribers that will not be released in any other way, as well as material that might be later on released for the public. There's also a certain amount of old stuff i have never released which will be selectively released to subscribers.

I'm also thinking of including other material that would be interesting to listen to, like collections of loops i have been working on, remixes of existing tracks, bootlegs or else. I'm especially keen on trying the loops concept as i myself like to listen to them a lot once i get a good one going. Just to be clear, these loops are not production material for you, it's only for listening. It's pre-production material for my forthcoming solo works. "Rakka" album was mostly made with such loops.

I will want to continue with "no fillers" mentality that i have always tried to adhere to my productions, but at the same time open a door to and share parts of the process and even failures in my productions.

You can subscribe at Bandcamp here.

The Vocalcity 20th Anniversary Remaster is available now at Forced Exposure and Bandcamp. The Multila remaster is available at Bandcamp. Rakka is available at Forced Exposure and Bandcamp. 500-Push-Up, the collaborative album from Vladislav Delay and Sly & Robbie, is available for pre-order at Forced Exposure. 500-Push-Up is out August 28th.

Tone Glow Mix

Every now and then, artists will provide a mix personally made for Tone Glow. Mixes will always be available for streaming and download.

The mix contains some of my favorite jazz ballads which I live dubbed in the studio.

—Sasu Ripatti

Download links: FLAC | MP3

Streaming link: YouTube

Still from Illuminated Texts (R. Bruce Elder, 1982)

Thank you for reading our special midweek issue of Tone Glow. If you have the energy, take some time to check in with those you care about.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.