Tone Glow 015: Maggi Payne

An interview with Maggi Payne + an accompanying mix, album downloads, and our writers panel on Pantayo's self-titled debut

Maggi Payne

Maggi Payne is a composer and artist currently based in California. She was the co-director of the Center for Contemporary Music at Mills College for 26 years, and has created a number of audio, video, and installation works throughout her decades-long career. Recently, Aguirre Records reissued two of her albums, Ahh-Ahh and Arctic Winds. Joshua Minsoo Kim and Payne talked on the phone on April 30th, discussing her childhood, flutes, the “potential” found in the sounds of nature, and more.

Maggi Payne at Glacier National Park, May 2008. Photo by Brian Reinbolt.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Hello, this is Joshua!

Maggi Payne: How are you doing?

I’m good, how are you?

I’m fine, sounds like you’ve been really, really busy.

I guess I have. I try to keep myself busy, that’s sort of how I—

Deal with things. (laughter).

If I’m not doing something I feel like something’s off.

Yeah, exactly. (laughs).

Are you like that too?

Yeah. It’s a good strategy, I think.

I wanted to ask you about your childhood. What’s the earliest memory you have that’s related to sound or music?

Oh, that’s really interesting. I was just looking up some stuff in this old baby book that my mother maintained for a while. One of her entries says that I really did not like loud sounds (laughter). However, those were the days when you didn’t have a whole lot of toys, so she used to throw a bunch of pots and pans in my playpen and she said that I stayed in there for hours and hours without needing attention (laughter), just playing with everything. So that’s pretty early, but later on, my mom had me take piano lessons. I never really connected with that instrument very well and when I was nine years old I heard flute somewhere and I knew that was for me, so I got right on it.

It was amazing because I had this wonderful teacher named Harold Gilbert. The flute’s a very hard instrument to play—I mean they all are, but to even get a sound out of it, you know? I just fell in love with the air going through the flute (makes the sound of air going through a flute) and moving the keys so the air changed pitch, and all the whistle tones and clicking the keys… I confessed that to him and—to his credit—he said, “That’s right, but in the meantime learn some Handel sonatas.” (laughter).

I didn’t really need his permission; I just thought it was really cool that liking those sounds was all okay. I was raised in a spot in Amarillo, Texas where farmland changed to desert. We were sort of on the desert side of town where we could see out into it forever; there’s nothing behind us at all except cow pastures. I learned to love things that were abstract because of that—you know, the beauty of nature, every little crack in the earth. It’s interesting because there weren’t plants, no trees (laughter). Something just drove my passion towards experimental music right from the get-go.

It’s super interesting that you mention you were drawn to the flute and the various sounds it made, as well as the physical act of playing it. It’s funny it was all even there even then given your works, like with The Extended Flute. When did you start experimenting with extended techniques on the flute?

Age nine (laughter). Seriously! It was always a part of my practice. Most people warm up playing long tones, but I warmed up playing whistle tones, and then moved on to long tones. Yeah, I think it was just there from the start.

That’s awesome.

Yeah. I always loved the sound of the desert wind—we lived in a very windy location—and the way it howled through the house and would make things rattle. All those sounds… the amazing thunderstorms, and the hail storms coming down on the roof (laughs). All of that stuff was so exciting for me.

Payne at Lake Michigan in Chicago around 1966. Photo by Ted Ashford.

I love that so much of your interest in music was there when you were younger. On Arctic Winds, you took recordings of specific locales and integrated that with different sounds of your own. The description for the album says that “each sound [was] carefully selected for its potential.”

Exactly.

What is the potential you heard in these sounds, the ones you heard as a kid? The desert winds and hail storms.

I was driven by those early experiences of nature. Thunderstorms just shook you to your core, and there’s the beautiful lighting that happens, of course. When I’m talking about sounds I used in my works, I’ll hear a sound in nature that I think is really cool. It’ll be like, “Wow, isn’t that beautiful?” But no matter how beautiful it is, if I can’t immediately imagine how it would fit into my sonic world and be developed in some way to become a part of a piece, I won’t record it—I’ll just enjoy it. That said, I have thousands of hours of recordings (laughter) ever since I got my first recorder since I was ten.

Do you remember what that recorder was?

It was a Webcor. It had a magic eye. The recording level meter had this horizontal tube where if you were getting too loud, the—whatever it was—would hit in the middle. It was so beautiful (cheerful laughter).

You said you wouldn’t record sounds if you couldn’t see it fitting into your works. Are there specific sounds you’re drawn to, or is it just that you’re hearing a sound—something you’ve even heard in the past—but it’s just that in this particular moment it clicks for you?

I think it’s the latter. Sometimes there’s minor fluctuations or deviations that are really interesting; it’s these details. It’s not always the entire sound that I’m interested in, but instead just a small band of that sound—a small part of that spectrum—that intrigues me. And I can hear potential in that and how it can be used.

You’ve made a lot of recordings. Is there a particular recording you’ve taken where you were proud or really surprised by how you utilized it?

In the house that I live in, there’s this floor furnace that makes these beautiful, beautiful sounds. I’ve used that in a few pieces. I never tire of that sound. I live in California so for the past three winters, I haven’t turned the heater on except for the pilot light. But that’s enough to make this resonant sound that I really love. If the refrigerator goes on that gets through into that sound, or it can be a timer that makes a strange sound that gets in there. So that’s a favorite sound, and just a sound I enjoy in the house.

What recordings have you incorporated that into?

I’m not sure, let me look that up. (starts humming and looking up information). I used it in “Distant thunder.” I called it a “resonant floor furnace” (laughter).

Payne at Angel Island in the San Francisco Bay for Robert Ashley’s ‘Music with Roots in the Aether’, David Behrman segment. June, 1976. Photo by Patricia Kelley.

In the ’70s and afterwards, you were working with musicians like David Behrman and everyone in that scene. Prior to this, were there other artists you felt were creating the kind of music that you wanted to make?

That’s a tough thing to answer. I’m thinking of even earlier, like when I was playing [Edgard] Varèse’s Density 21.5 at around 13 years old. The beauty and power of that piece, its modularity and the way he structured it—that was a seminal piece for me. Learning it so young, and learning other contemporary works at such a young age was pretty amazing.

I don’t know what to say… it’s just that everything was exciting for me. Meeting so many composers was also exciting. I just had this incredibly independent spirit where I didn’t really take on the characteristics of anyone around me. I didn’t say, “That’s really cool how this composer does this, I’m gonna be like that.” It was more dependent on the resources I had at hand.

When I wrote my first major piece in my senior year of college—I had composed other pieces when I was younger—it was called Reflections and it was all extended techniques. And that just came from me; I didn’t know any other pieces like that. I was just so desperate for a larger sound palette, and when I finally got to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, this wonderful acoustician, James Beauchaump, had a classical studio there. He had some Moog modulars and it was like, “Okay, this is it, this is what I’m looking for.” I had already played [Mario] Davidovsky’s Synchronisms for solo flute and electronics in college by my sophomore year, maybe freshman. I was way into that and of course [Luciano] Berio’s Sequenza.

I could finally get my hands on the electronics at Illinois and start making sound. Gordon Mumma was there that year and he said, “You know, you should go to Mills [College] and study with Robert Ashley.” So I did (laughter). But while at Illinois, I just took the Moog synthesizer and the Buchla. I loved exploring that world, it’s what I was looking for at the time. I still use them. And I built my own Aries synthesizer as well.

You’re no longer the co-chair at the Center for Contemporary Music (CCM), right?

Both Chris Brown and I retired at the same time in the hopes that we would get a full-time job replacement. We left in May of 2018. I’m still around there a lot (laughter) and we’re both still on the composition faculty so people can study with us through the school privately.

You were the co-chair for a long time.

1992 to 2018.

A good amount. Work in such an institution is going to be collaborative to some degree, but were there any specific things that you specifically fought for and wanted to happen at Mills College?

Just about, um, everything (laughter). I think the most major one was when David Behrman and Robert Ashley left Mills around 1981, and there were rumors that the then-head of the department wanted to close down CCM and the Public Access program. Or turn it into a research institute. "Blue" Gene Tyranny and I, as well as a massive group of other people fought that like crazy. And we did win out, though Public Access was diminished—it was still kind of there, but not as much as we wanted. But at least we saved the center.

Is there anything else you were fighting for later on that was memorable?

All this work was us fighting together, to keep this core spirit of individuality and experimentalism. Everybody was on it, I had such amazing colleagues—Fred Frith, John Bischoff, James Fei, Alvin Curran, Laetitia Sonami.

You collaborated with Ed Tannenbaum for Ahh-Ahh, how do you approach writing compositions while keeping in mind another medium of art?

Those pieces are actually about the only ones I did that use rhythm (laughs). It was a wonderful collaboration space—it was so much fun. He’s a remarkable person—he built his own digital video processor—and he’s deeply into computers and did these amazing things, and still does. I was so happy when he asked me to write pieces. We discussed things and out would come the pieces and he was always happy with them, so yay! (laughter).

The “Ahh-Ahh” piece was the one where he was most specific with what he wanted. He said he wanted this sense of an ocean, although I remember him saying something about whips and snakes. He said he didn’t say that, but I know better (laughter). It’s fun to tease him about that (laughter). We’re still great friends.

The titles for your pieces are evocative and often match the music. Do you typically name them after creating them, or do you have a title in mind beforehand? On Ahh-Ahh you have the track “Hikari,” which translates to “light.”

Oh, thanks, I didn’t know that (laughs). I think Eddie named “Hikari.” I named “Flights of Fancy” because of the visuals, so that was after the piece and visuals were done. He did the visuals to my music, it wasn’t the other way around. He calls it “Viscous Meanderings.” “Gamelan” was the same idea. I think “Shimmer” was my title, “Back to Forth” was definitely my title, and I named “Ahh-Ahh.” So, he named “Hikari” (laughter). Hard to keep those things straight, but yeah I typically name the pieces after they’re done to see what they reveal for me. It’s almost like a strange collaboration with the sound world to see where it leads me. That potential I was looking for leads me to treat the sound in certain ways. It kind of establishes what that piece is about, and I go from there.

In what ways have pieces led you? What exactly is it revealing?

It reveals to me where to go next, or what was so specific about the sound’s potential that was drawing me to it, that was wanting me to make sure it came out in my work. I record a lot of stuff, so deciding what can work together is a substantial process. In terms of the earlier electronic works—like the Moog pieces—or even the newer ones, it’s a different world because there’s no sound already pre-existing. I’ve always approached that with quadraphonic in mind. It’s critical to consider not just the sound but where that sound is going to lead me, where its origin is going to be to the listener and how it’s gonna move through space.

I have these images of a sound starting way above your head as a pinpoint, and slowly coming down spiraling down wider and wider into space around the four speakers. I always have images of those trajectories in mind when creating electronic works.

Can you speak to the physicality of the music you make? How do you ensure that what you experienced when you recorded specific sounds—like the thunderstorms—transfers when someone hears your work? And what’s your approach like with your compositions that are purely electronic?

I think it all wraps around together. I’m always thinking of architecting a space. It builds one geometric shape after another. It might expand and stretch far past where the speakers appear to be and it may come back, slamming in really fast to a pinhead, focusing really tightly in the middle of your head. And then it may slowly expand back into an entirely different shape. By having these entities move, or start from far in the distance and seem to come closer to you, and through you, and back behind you, I’m always trying to choreograph or sculpt the space. It’s always been present in my work ever since I got into electronics. It’s always been important to think about spatialization.

Has the process changed at all throughout the past few decades of making music?

Technology (laughter). I always think we’re tied to the technology and what you can do with it. I was really fortunate because I worked those four jobs for a number of years. I think it was actually three jobs for 11 years and for two of those years, I worked four jobs simultaneously. I piled up enough to afford the Sonic Solutions digital audio workstation [The Sonic System] and that was a breakthrough for me for sure—just to be able to get it all in a totally digital domain.

I just did a big installation piece, and it’s getting so hard to record the outdoor acoustic world because of noise pollution, and that’s been a big part of one thread of my approach to composition—using sounds that occur in the real world. I really appreciated the Sonic Solutions NoNOISE software and, more recently—because that’s no longer around—iZotope. It’s just that it’s difficult to capture outdoor sounds even in the middle of the night—the freeway may be less busy but the freight trains come (laughter). And I love all those sounds but I don’t want them in my piece! (laughter).

What goals do you still have for yourself? What do you still want to achieve in your works?

I confess that I never repainted my kitchen when we moved in back in ’88. Instead, the walls just have note after note after note attached to them about the pieces I want to do—ideas for both video and audio works. There’s just never enough time (laughs). There’s just so much I want to do. Hopefully I’ll get around to them.

Payne with the video component of Circular Motions, a work she made that involved her movement with various objects as Ed Tannenbaum controlled a digital video processing system. 1982.

Is there an idea that you’re really interested in tackling soon?

I’ve been pretty busy this past year composing pieces, but I’m just getting back into the idea of this mechanical world and all those wonderful sounds that devices make. I’ll probably put together a piece in that vein.

Like what type of mechanical sounds?

I’ll try to describe what these things are (laughs). I walk down the street and there’s this big metal container that’s making these beautifully harmonic sounds through these vents and the sides. I’ve been recording that.

Do you mind sharing what street that’s on?

There are two of them on Berryman St. in North Berkeley. It’s not just a hum, like a 60 Hz with harmonics hum—it’s higher. It’s been difficult because the first time I recorded past midnight in the fall and it was okay in terms of traffic but the crickets were out (laughter). Come on, guys—stop it! (laughter). I love you, but— (sighs). But now that the traffic around here has died down, the birds are out (laughter). I love birds, I use them all the time, but it’s so wonderful and so challenging. I did a huge piece where I was using bird sounds like crazy and tried to get all the extraneous sounds out of those recordings and now it’s the inverse. It’s so funny the way the world works (laughter).

Have you been recording more, now that there aren’t as many people outside?

Well, there are a lot of really healthy and active people in my neighborhood (laughter). I actually recorded some of those aforementioned units yesterday and with social distancing, it’s challenging. Everyone is walking in the middle of the street, but people in the area are being so conscientious. I’m huddled up against this thing and people are walking their dog and I don’t know what they’re thinking (laughter).

Do people ask what you’re doing?

Yeah they do (laughter). It’s like, “No, don’t talk now!” (laughter).

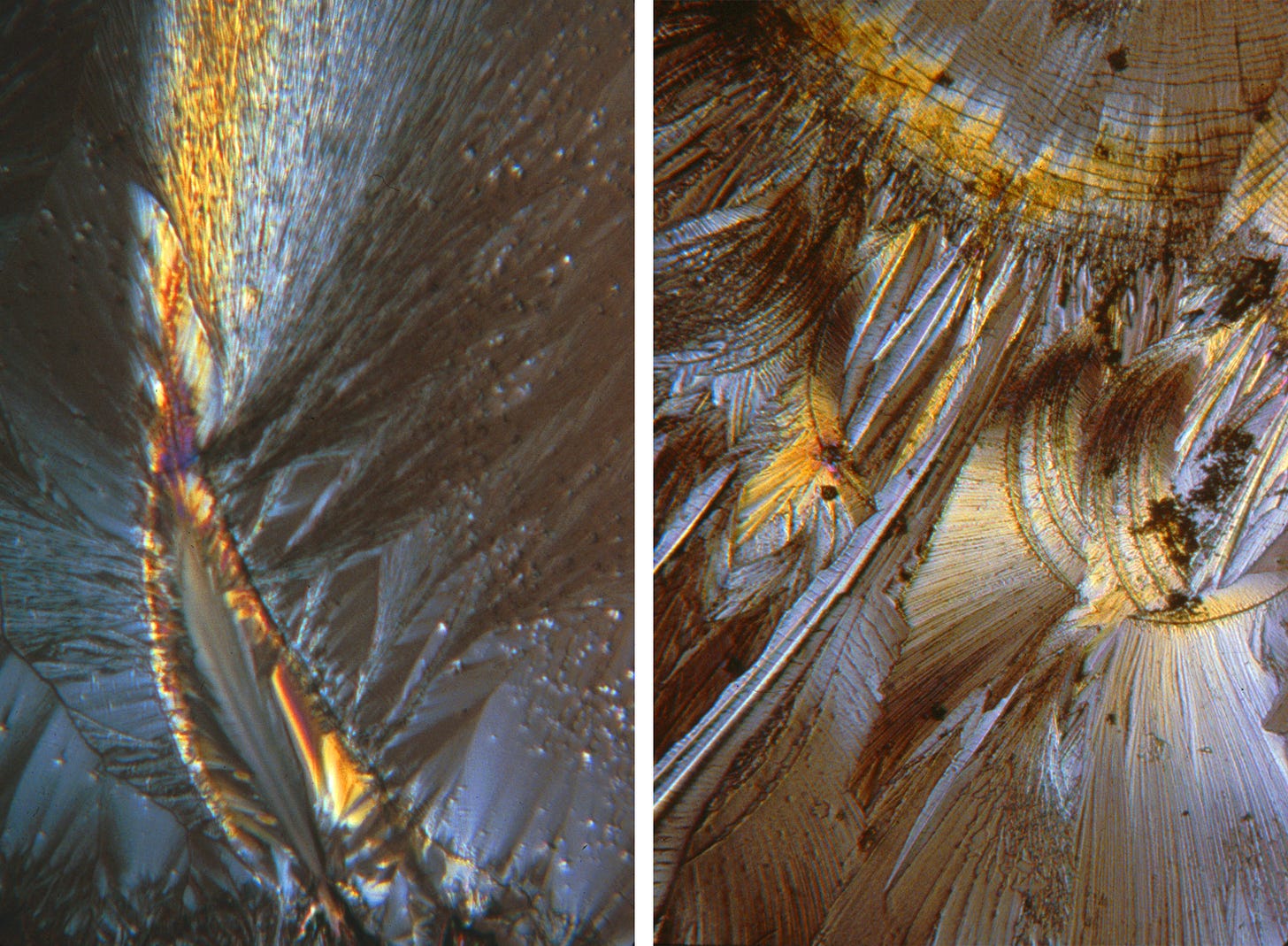

Images that Payne took of crystals with her father’s medical microscope around the time she made Crystal.

What sort of ideas do you have for visual works?

I don’t know if this will ever happen but I did a piece called Crystal back in, I think, ’82. I used my father’s medical microscope and a large variety of chemicals that crystallize. I wore out his microscope stage because I was having to track the crystals that were growing in real time going upside down and flipped from the way that I had to move the slide stage—it was really quite interesting to do. I would need a new camera to do that, and a new microscope, and I’m not sure if I can get my hands on those chemicals anymore. That is a dream, though, for sure.

That’d be really nice.

It would be torture, but it would be wonderful torture (laughter). It was so hard. And my hands would bleed.

Oh my God.

Yeah, from moving the slide stage. I’m fanatical whenever I do this stuff—I’m not talking 2 hours, I’m talking 18 hours a day. I can’t help myself (laughter).

Do you always go to such extremes? Does this “wonderful torture” sort of mentality always exist when you do your work?

I’m teasingly saying that, of course (laughter).

Yes, yes (laughter).

But it requires a lot of discipline. When I’m shooting video I want to make sure it’s at the correct angle. We do a lot of canoeing and it’s always like, “Okay Brian [Reinbolt], don’t breathe for the next… hour.” (laughter). “The water here looks great.” I thrive on it. I can’t seem to manage to do things that are easy (laughter).

That’s good, though. You’re always pushing yourself.

A challenge is good. Particularly a challenge you make for yourself. It’s part of what keeps us going.

Were your parents interested in the music you were making?

(laughs). My mom, I love her so deeply—and she was so supportive—I was so fortunate. I did not come from a musical family; there was no music in the house aside from myself and my brother. My mom encouraged us to engage in music, but she was a monotone. She couldn’t sing a song, so that was kind of fascinating. But she was a marvelous support and I was fortunate that my father had the means to keep buying me new flutes.

I ran through flutes really quickly, I was always needing a new flute. By the time I was in seventh grade, he had bought me a really high quality flute that allowed me to continue to progress really quickly. In the tenth grade, my parents made a deal with me that they would buy me this really good flute for my high school graduation, but it would be the last present I would get for my entire life. (laughter).

So if I ever got married—which I never did, thankfully—or for college graduation, it didn’t matter; this was the present that would cover all presents in the future. I jumped on that deal, I thought it was the best deal I had ever heard, and I still do! I was so happy, and it’s a fabulous flute—I still have it. I’d managed to save up enough money playing gigs in Chicago to buy yet another flute later, but I still love that flute.

How many flutes do you estimate they bought you up until that final one?

(thinks and counts out loud). Probably three flutes until they bought me this really good one that was part of the deal. They stuck to that deal by the way (laughter).

Did they remind you about it as you got older?

No, they didn’t need to! I was happy, and they knew.

What was the flute that they got you?

The one they bought me was a Haynes. And the one I bought myself was a Powell.

Payne at Lake Tahoe, 2016. Photo by Brian Reinbolt.

You mentioned that not getting married was a great thing. Can you expand on that?

I think it was just the…

It’s okay. You won’t offend anyone! (laughter). Don’t worry.

I think it was the need to feel independent and be totally responsible for myself. I’ve been in many relationships, and in a long term relationship with my partner Brian. We’ve been together since 1986 (laughs). We bought a duplex in ’88 and he lives in his half, I live in my half, and there’s no door in between. It’s heaven.

It’s heaven! I love it. You have your own independence but you can still be with him when you need to.

Exactly. There’s no hassles about financials—we’re both equally independent. There’s just so much out of the equation. He doesn’t have to worry about my super messy house, and I don’t have to worry about him not cleaning his house enough (laughter). I’m clean but messy, and he’s very tidy but maybe not as clean.

Did you get pushback from people about that, be it from your parents or your friends?

My parents never knew.

They never knew that you two didn’t get married, or about the living situation?

They knew I didn’t get married, but I lost my mom when I had just turned 22. My dad never asked (laughter). He was a very quiet person, he would never pry. It took a lot to get anything out of him.

Thanks for sharing all that, I appreciate it.

More than you needed to know! (laughs).

I’m glad you said all of that. That sort of thing goes against the norms we have in our society and there’s probably gonna be someone who reads this and will be thankful it was said.

Well, you know, so many people we talk to say that it’s a fabulous idea (laughter). I mean, you have it both ways, right? I mean, yeah! I have my own studio and he has his workshop in the back. What more do you want?

Do you have any advice for young people interested in making experimental work?

Just do it. It’s just so much fun. It’s so rewarding to know what you want to do in life and to be able to pursue that.

Payne at Stampede Reservoir near Truckee, CA. She is recording VLF signals after canoeing several miles to distance herself from power lines. July, 2013.

Is there anything that you wanted to say, that you’d like to right now?

When listening to pieces, I tend to close my eyes and just deeply experience them. I crawl inside them and become a part of the piece. It can be so immersive. Let the music take you somewhere, take you on your own journey within the sound. Float freely in that sculpted space so it can take you out of the reality in which you live for a little white. It’s like a mini vacation.

A mini vacation? I love that. And I think your works definitely do that. When I listen to them, I feel like I’m in a space where I’m fixated on all of a composition’s sonic properties.

Thank you. That’s exactly what I hope to do with my works.

When I’m outside and let all the sounds of nature wash over me, it’s the same experience with the pieces you have involving location recordings, though it’s a bit more guided.

That’s right, but I hope it gives you enough room to move in your own fantasy, with your own experiences. It’s a really critical part of my work and it always has been—to go for a deep dive, to let everything off your shoulders for a while, to take a deep breath.

Are there any other composers or artists that you feel accomplish that really well?

There are so many, that would be really hard to do (laughter). But you could certainly point to Maryanne Amacher, Francisco López—there’s just so many. And I experience all music that way, even classical music.

I feel that. When people talk about “deep listening,” I feel it’s usually reserved for Pauline Oliveros’s works or music that’s similar. I sometimes tell my friends that I think we should be applying that idea to all music. There’s so much music beyond what’s typically described as offering this “deep listening” experience that can provide it.

I totally agree with you. I’ll find an instrumental piece—a Ligeti piece or whatever—and I’ll go between closing my eyes, experiencing that totality, and then I’ll hear a detail and open my eyes for just a second (laughs). Maybe I wanna hear that second violin part a little more intensely, and then I can hone in on it—visually as well—and go back into my world again. It’s a play between the two: the reality and that inner reality. It really just takes you somewhere so very special.

Reissues of Maggi Payne’s Ahh-Ahh and Arctic Winds are available on the Aguirre Records Bandcamp page and website.

Tone Glow Mix

Every now and then, artists will provide a mix personally made for Tone Glow. Mixes will always be available for streaming and download.

As a composer (of electronic, electroacoustic, soundscape, and acoustic music), an installation artist, video artist and recording engineer, I thrive on a wide diversity of approaches to creating music and images.

In Immersion, Bay Area Soundscape, I created a journey where the listener takes a very long walk fully immersed in the sounds of nature. A windstorm turns into a rainstorm, forming a stream that flows into the ocean where the traveler swims, surrounded in waves, then rests on the seashore of a bay into which the ocean flowed. Submersed in the bay (captured by hydrophones) they journey underwater until they land on a shore inhabited by frogs, then walk to drier land where they encounter crickets late into the night, awakening to birdcalls as dawn breaks.

Immersion was originally a thirty-minute discrete 8-channel work, commissioned by the Berkeley Arts Commission for the Downtown Berkeley BART plaza, where it was played continuously throughout the day for two three-month periods. This stereo version is a more succinct 12-minute experience.

As an environmentalist since the 1970s, several of my works address environmental concerns. With Immersion, I used some recordings I made from as early as the 1970s because current noise pollution makes it impossible to capture some of the sounds I hoped to record again, despite sophisticated programs designed to help clean up noisy recordings.

—Maggi Payne

Download links: FLAC | MP3

Streaming link: YouTube

Download Corner

Every issue, Tone Glow provides download links to older, obscure albums that we believe deserve highlighting. Each download will be accompanied by a brief description of the album. Artists and labels can contact Tone Glow if you would like to see download links removed.

Marcel Duchamp & John Cage - Reunion (Takeyoshi Miyazawa, 1968)

Despite only being a little over seven minutes long, Reunion is one of the most important fluxus documents. More than just a record of a happening, it’s in many ways a capstone to the movement itself, at least as it was known to the major players at the time. The concept is simple: John Cage and Marcel Duchamp play a game of chess on stage, and the moves made on the chessboard produce not only the sounds of the performance, but influence where they appear in the space of the room. The piece was conceived by Cage, though not composed by him. The event’s composer list reads like a who’s who of experimental music at the time: David Behrman, Gordon Mumma, David Tudor, and Lowell Cross contributed to the composition, as well as provided the live music made in response to the game unfolding on stage. Cross says of the performance in a 40 years after-the-fact post-mortem: “Cage told me that he was naming the piece Reunion because he wanted to bring together artists with whom he had been affiliated in the past in a homey but theatrical setting.”

Cage and Duchamp sat in comfortable chairs, sipped wine, puffed on cigars, and chatted with the performers nearby as they leisurely played a game of strategy. (Interesting to note, Cage was either bad at chess or Duchamp was very good. Cage lost every game, even with Duchamp playing one with the handicap of a missing knight.) It’s a deliberately understated affair; indeed, the local music critics described the event as “mightily boring,” and the piece concluded to an empty house that was full when it began. It was really just meant to be a comfortable gathering of Cage and his friends, and a victory lap to celebrate the spirit of collaboration. Reunion reminds us that making things happen is only half the point; fluxus became a formidable movement because they all made it happen together. —Shy Thompson

No Artist - 幻の音風景 水琴窟 (Maboroshi no Oto Fuukei Suikinkutsu) (Nippon Resort Center, 1991)

A Suikinkutsu is a garden ornament that create music via water droplets. These droplets land in a pool of water that’s housed in an overturned pot, which leads to a metallic ringing. There are a handful of albums that feature recordings of such devices, but the recording quality of this one is particularly great. This CD comes with specific instructions that roughly translate to the following:

This recording is supposed to reproduce the sounds you hear when crouching over the Suikinkutsu (which is buried in the ground). Thus, playing at low volume is recommended. If you usually set the volume at 10, the appropriate position for this CD is 5.

Naturally, I ignored all this for my first listen, playing it at a higher-than-normal volume to hear every detail—I don’t regret it. Each of these three tracks have their own appeal: The first has sparse droplets, allowing one to hear both the water and metallic sounds resonate clearly; the second couples that with winds and birds and other nature sounds; the third is akin to the first but slightly more rowdy, the clanging a bit more forceful.

Through my speakers, I let each individual note ring out and tickle my ear. Played loudly, you feel the strength that comes in every single drop, and it’s enough to induce chills. The busyness of the third track allows for a pretty series of tones, making the suikinkutsu occasionally feel like a more typical percussion instrument. But more than anything, it’s the unpredictability of these pieces that makes their long runtimes worthwhile—you never quite settle into a particular groove. Played quietly, one can imagine hearing these sounds nearby, as if your ear is place near the suikinkutsu’s opening. It forces you to listen more intently, to search out these sounds instead of letting it come over you. Whatever way you choose to listen, the simplicity of these sounds proves inviting, constantly hinting at how mesmerizing individual drops of water can be. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

St. GIGA - Ambient Soundscape 5: NIGHT & MOON; Full-moon Mystique, Bali Island (St. GIGA, 1992)

St. GIGA is probably best known these days for their role in broadcasting the Satellaview video game downloads for Nintendo’s Super Famicom in the mid-to-late ’90s, but before becoming involved in broadcasting games, they made a name for themselves as the very first broadcasters of satellite radio. They were known for their freewheeling lack of structure, and for their interest in the unusual and experimental. Under the vision of director Hiroshi Yokoi, they broadcast a mix of new age, jazz, and field recordings they called “biomusic.” The popularity of St. GIGA’s broadcasts allowed them to send their staff to locations across the globe to record, and this is one such recording. They’ve collected sound from such far-flung locations as the Hokkaido countryside and Trinidad and Tobago, but this recording from Bali is unique in that it’s one of the few (or only) in their Sound of the Earth series that features more traditional music. Sort of.

Balinese gamelan is being played inside of a place of worship, but these recordings were made around it rather than inside of it. The music ranges from audible, to perceptible, to nonexistent depending on where the microphone is placed and how much nature is between it and the temple. Hearing the clattering of gongs lower in the mix than crickets and birds paints a lovely scene, as does the music being drowned out almost completely by heavy rain. The recordings start off with the music at the fore, transition into a still life of nature, and end with both in perfect harmony. Gamelan is undoubtedly a beautiful musical tradition, but so is the natural world that gave rise to it. They deserve equal billing here. —Shy Thompson

Writers Panel

Every issue, Tone Glow has a panel of writers share brief thoughts on an album and assign it a score between 0 and 10. This section of the website is inspired by The Singles Jukebox.

Pantayo - Pantayo (Telephone Explosion, 2020)

Press Release info: Pantayo explores what’s possible for contemporary kulintang music with the atonal blend of kulintang ensemble instruments with vocals and electronic production. The album features eight diverse songs speaking to Pantayo’s musical influences as queer diasporic Filipinas. Produced by Yamantaka // Sonic Titan’s alaska B, Pantayo was written and recorded from 2016-2019 in Toronto.

Pantayo is an audio diary of how the ensemble has grown together as writers and performers. The songwriting process started with members workshopping and performing traditional kulintang pieces from the Southern Philippines, often instrument-switching on the kulintang, agongs, sarunays, gandingan, bandit, and dabak. Adapting kick drums and synths to the modal tuning of the gongs further expanded Pantayo’s ability to incorporate modern musical expressions such as punk and R&B.

You can purchase Pantayo on Bandcamp.

Shy Thompson: As a mixed race person with a complicated upbringing, Pantayo’s debut record makes me feel a bit jealous. I was deliberately raised in such a way that my experience with the cultures of both of my parents was limited, so that I could have an “easier time” in America. I didn’t get to grow up speaking my first language, and now I’ve mostly lost it. My stepfather’s culture was different than that of both of my biological parents, and also kept just the slightest bit out of reach. Growing up seeing glimpses of cultural touchstones I was never allowed to understand really did a number on me; I have an experience unlike that of almost anyone, and I don’t feel like a part of anything in particular. The reason I feel a tinge of jealousy when I listen to this record is that I can tell the difference between a mixing of cultures that makes the individual components nigh-unrecognizable, and one with a purpose and intuitive understanding. Pantayo knows who they are and what they’re doing.

Music like this is important. It exemplifies the experience of a diasporic people: cultivating the traditions you identify with, respecting them, and ensuring they don’t erode against the tide of other cultural forces you may find you’re swimming against. The kulintang influences are beautifully adapted to this assortment of songs that draw from a familiar language of R&B and dance music. I love the rings, clangs, and chimes of these resonant percussive objects; I love the deep, pounding grooves that drive forward tracks like “Bahala Na” and the stellar instrumental “Bronsé”; unfortunately, what I don’t love as much are the things that feel the most familiar. I find myself most engaged with the minutiae—the unique textures, the musicianship—and not very engaged in the structure of the songs themselves. As a pop album, there’s not a lot here that speaks to me, but as a document of who Pantayo are and what they have to say, I hear them loud and clear.

[4]

Sunik Kim: I almost didn’t write this blurb because even though Pantayo failed to move me at all—I had a really hard time even getting through a single listen—I initially felt no need to publicly give it a negative review. Normally I pan things I believe take up too much cultural space, things predicated on blind hero-worship and hype, and work that represents trends I think are stupid. ‘Pop music with kulintang sounds made by a queer diasporic Filipina-Canadian collective’ is not a trend I’m desperate to take down; and, after reading some interviews with the group, I’m into their broader political project, one that’s wrapped up in the fascinating kulintang tradition (which I wasn’t aware of, and now want to learn more about!), its history, and contemporary conflicts around resource extraction from Indigenous land.

Ultimately, none of this changes the fact that the music itself is, at its core, dull, textbook R&B-influenced indie synth-pop—we have the slow jam (“Divine”), the four-on-the-floor stomper (“Heto Na”), the wind-in-hair Future Islands end-credits track (“V V V (They Lie)”), the post-punk-influenced jaunt (“Taranta”), etc.—where the rich kulintang sounds mostly play a decorative, formal role rather than a foundational one. It’s tempting to direct artists when critiquing—“if only they ditched the rigid pop form and the cheesy synths and...”—but ultimately that’s besides the point; Pantayo is what it is, and that’s how I'm evaluating it. I’m not mad it exists; but it’s not something I would ever listen to beyond the context of writing this review.

[2]

Joshua Minsoo Kim: The reality is this: Western cultural imperialism has made it challenging for non-Western artists to create work that’s perceived as culturally “authentic.” It’s a bullshit thing to be criticized for, especially when one considers the systemic barriers in place that make it hard for them to make such art. Even then, what that art should look like is often bullshit, too—so many White people I’ve talked to in my life only consider art from Asian countries to “be Asian” if it’s firmly rooted in tradition. What this does is paint these artists into an even smaller corner, one that doesn’t allow for progression and growth and a broadening of Asian art at large. At worst, it leads them to grapple with that forced-upon identity, with artists often burrowing deeper into it or retaliating against it. The art, then, primarily functions as a response to the West instead of something organic. It’s dispiriting—a constant reminder of the inequitable world we’re in.

When I listen to Pantayo, I hear a group of five Filipinas uninterested in what anyone says about them—they’re making music that feels distinctly them, and that’s what matters. Part of the reason one can sense that is because no one’s ever combined kulintang with pop music before, at least not like this. Joey Ayala at ang Bagong Lumad’s “Mindanao” ended with a brief flurry of gongs, and Kuh Ledesma’s “Ethnic Variations” was a one-off interlude in an album filled with pop ballads, but Pantayo aren’t afraid to be more ambitious, mixing kulintang with a variety of pop styles. What results, however, is more of a layering than something interwoven, reminiscent of the kulintang-inspired trip hop of EK’s Dialects. It’s deeply unfortunate: the pop songs aren’t strong enough on their own, while the kulintang-heavy passages don’t ever dazzle as much as traditional recordings; in meeting somewhere in the middle, they’ve left me with two incomplete halves rather than something whole. Still, despite my disinterest in virtually every song here, Pantayo is an album I’m happy exists, and that’s more than I can say for most albums.

[3]

Oskari Tuure: Pantayo sits on the fence between two very different genres: an ancient form of traditional percussive music that seems to operate within its very own tonal boundaries, and cheesy pop music. Pitting the ageless sound of the gongs against modern synths, basslines and songwriting is ambitious, but sadly the elements don’t work together and mostly just end up sabotaging each other. The most interesting facets of the kulintang music do not have enough room to properly assert themselves, and the pop writing is not strong enough to make the tracks particularly engaging listens. The range of different sounds a kulintang ensemble can produce is enormous, but on Pantayo it has to watch the action from the sidelines instead of being the star of the show.

Merging traditional instruments with pop is not something new and can work very well, but everything here just feels like a missed opportunity. One of the rare parts where the musical combination of the two genres works well is the instrumental first half of “Heto Na”—the single-note bassline serves as the grimy foundation to an ominously dissonant percussion solo. There’s an achingly tangible tension between these two layers, but it all gets thrown away when the vocals come in. The tone of the singer’s voice is almost mocking, as if she knows how she’s transforming the song’s latter half into something that’s hard to take seriously. Another highlight is the production on “Taranta,” where an IDM-esque beat tirelessly carries the track onwards, as jazzy chords punctuate the manic ice crystal sound of the gongs.

[4]

Evan Welsh: Remember the Kombucha Girl meme? My first few listens through Pantayo essentially mirrored the torn and rapidly-shifting impressions expressed in the viral Tik-Tok—wrapping my head around the pairing of gooey ’80s R&B synths and vocals with the atonal chimes of kulintang pot-gongs, like on “Divine,” took multiple replays and an internal dialectic. At the end of that experience, I was able to discern how I was feeling about Pantayo’s experiment of modern recontextualization: I love it.

Pantayo is a pop album that, without the outstanding integration of the traditional Filipino percussion, might feel like a collection of empty pastiche. “V V V (They Lie)” and “Kaingin” both begin as relatively straightforward electro-pop ballads, the former akin to acts like CHVRCHES and the latter expressing the grandeur of Hounds of Love-era Kate Bush. The distinct, lingering presence of Filipino music that made “Divine” hard for my uninitiated Western brain to compute is what makes it feel exciting and intriguing. The bright, metallic timbre of the kulintang accents, contrasts, and ultimately extends the possibilities of “Heto Na” or “Taranta”—tracks that otherwise play in a world of familiar electronic dance music.

“Bronsé” and “Bahala Na,” the two songs that place their focus almost entirely on the percussion, are individually hypnotic and mesmerizing but also remind the listener of the concepts of kulintang that invigorate the entire project. New, disorienting, and purposeful approaches to familiar styles of music is exactly what I want from pop music. Pantayo celebrate and highlight their unique voice with an album that has only served to reward my obsession as I become more accustomed to it; I’ve fallen more in love with its distinct qualities with every revisit.

[9]

Jeff Brown: Pantayo features a blend of upfront bass guitar and the percussive chime of a kulintang ensemble. The vocals are often dynamically synth pop with a sweet, memorable chorus that carries a serious message on closer inspection. Listeners are lulled in with dreamy repetitive hooks backed by dance beats, finding themselves singing words like, “They lie, they won’t ever tell the truth / No, never tell the truth, ‘cause they know they no good.” Subversion is a tactic often used in folk and punk to let your voice be heard. And as is the case with Pantayo, sometimes a subtler route is more powerful and far reaching.

[7]

Nick Zanca: Fusion is precarious and tempting. Blending disparate spices together is all trial-and-error—one hopes to arrive at a harmony of flavors or even a satisfying juxtaposition, but more often than not, all we’re left with after the first taste is imbalance. On paper, the press copy that accompanies Pantayo sets up a promising glimpse of the Filipina diaspora and a genre-agnostic introduction to an underheard form of traditional metallophone music. What I hear instead upon pressing play places an almost uncomfortable emphasis on pop structure. The kulintang instruments are treated as atonal accessories to front-and-center drum programming and lyrics that are better suited for an Ibiza-ready Café Del Mar lounge compilation (“I dream of eternity / come with me”). The gongs and drums are rarely isolated until halfway through (“Bronsé”), and even then, the moment is fleeting—they eventually hide out in the outskirts of the mix for what remains of the album’s 28-minute runtime. This is not to say there is no potential in the duality of Pantayo’s sound palette—no doubt that similar contrasts have yielded strong results before—but here, the organic and synthetic barely coalesce.

[3]

Jesse Locke: I’m lucky enough to live in the same city as Pantayo, and have followed their evolution with great interest over the past few years. Though I can only count the times I’ve seen the quintet perform live on one hand, Pantayo’s self-titled debut provides a gorgeous snapshot of their growth both as collaborators and genre explorers. While the chiming percussive textures of traditional kulintang music remain the foundation of their sound (as heard on this album’s instrumental centerpiece “Bronsé”), Pantayo use this as the scaffolding to construct unique tributes to various forms of contemporary pop. These eight songs may sound like a mixtape with their unexpected sonic zigzags, but as vocalist/multi-instrumentalist Eirene Cloma explained in the Q&A portion of Pantayo’s May 8th listening party, this simply reflects the members’ diverging tastes and experience getting to know each other throughout the four years of its recording.

Producer alaska B of Yamantaka // Sonic Titan (a band who are no strangers to bold sonic fusions themselves) deserves immense credit for capturing Pantayo’s various approaches so vividly. Cloama takes lead vocals on the spiritual lead single, “Divine,” a love song that might be devoted to a romantic partner, higher power, or both. “V V V (They Lie)” could be mistaken for Carly Rae Jepsen, while “Taranta” is a half-rapped, half-sung ode to sisterhood in the tradition of Destiny’s Child. Closer “Bahala Na” is tonally reminiscent of Angelo Badalamenti’s Twin Peaks theme until it spirals into another spellbinding percussive jam. Pantayo are at their best when they truly let their hair down, exploding into infectious danceable joy like the moment at 2:05 in “Heto Na.” Riding a squelching beat and pitch shifting their vocals until they become cartoonish schoolyard chants, this song’s closest comparison is OOIOO’s Gamel.

[8]

Matthew Blackwell: The rich, resonant gongs of the kulintang are tricky things. They need space to reverberate and time to decay. This makes Pantayo’s stated goal of adapting the kulintang into modern genres admirable but difficult. At times, they solve this problem by making the kulintang sit awkwardly next to music from another genre, as in “Heto Na,” when a lovely gong melody builds and builds until it unaccountably transitions into an in-your-face hip hop track at the halfway point. At other times, they subsume the kulintang into another genre, for instance when it is recruited into the percussion section on the smooth R&B ballad “Divine.” And finally, they simply allow the kulintang the foreground, as in the album standout “Bronsé.”

On top of this tripartite instrumental approach, each of the five members contributes vocals in a unique style. This means that to find a really great track here the listener needs to be drawn to both its deployment of the kulintang and the vocals of its singer in a sort of mix-and-match lottery of styles. I love the driving rhythm and the self-righteous lyrics of “V V V (They Lie),” in which, incidentally, the kulintang is barely there, providing a subtle background melody. Others will surely find one or two songs that strike the right combination for them. But this is the definition of a hit-or-miss collection of songs rather than a coherent album.

A couple of unrelated recent projects throw the potential of the Pantayo project into high relief. I’d like to see the kulintang given its due, perhaps by being transformed via hypermodern production FX in the way that Sote recently accomplished for the santour and the tar, which the aforementioned “Bronsé” suggests is certainly possible. Perhaps the varied and considerable vocal talents of the group could be turned toward a more coherent aesthetic, as in the multivocal neo-R&B group SAULT. Pantayo hints at successful future directions for the group. In fact, it hints at too many, as each of its tracks explores a path that only infrequently crosses the others. Now they just have to pick one to follow.

[5]

Raphael Helfand: Introducing microtonal Filipino percussion instruments into a pop sound is an exciting proposition. The best moments on Pantayo’s debut album exploit this synergy and take it to unexpected places. Opener “Eclipse” builds slowly on an ostinato rhythm, adding in elements of the kulintang ensemble and a sparse bass groove before the simple vocal refrain hits. The tonal melody clashes pleasantly with the eerie resonances of the gong-based instruments, leaving room for the rhythmic density beneath it. “Heto Na” takes a more energetic approach, showing off the ensemble’s full dynamics, accented by impeccable production from Yamantaka // Sonic Titan’s alaska B.

Other tracks, where electronic production takes over, are less successful. On “Divine,” the main percussion is a standard kit, with the kulintang, agong, sarunay, etc. taking on smaller roles. A mellow synth does little to carry the vocals, which feel saccharine without more interesting accompaniment. On “V V V (They Lie),” the gongs are almost entirely absent, and the singing devolves into an unexciting Sleigh Bells pastiche. Closer “Bahala Na” is one of the album’s better tracks, but it doesn’t quite save a disappointing back half, in which there just isn’t enough cowbell (metaphorically speaking). The lush rhythm and rich overtones of the kulintang and its companions are what give the good songs their edge. Without them, there isn’t much to grab onto.

[6]

Samuel McLemore: The Canada Music Fund, most famous for flooding the airwaves with forgettable and annoying pop and rock, takes a more respectable tack in 2020 by supporting the debut album of the Toronto based kulintang ensemble Pantayo. Kulintang is the name of an instrument and an ensemble, and the music that is played on both. None of this will be familiar to Western audiences but Pantayo aren’t trying to give us a traditional kulintang album. A more ambitious sort, they are attempting to fuse traditional kulintang forms and timbres with modern western pop genres.

The task of molding disparate musical forms into a syncretic whole can be shockingly complex but Pantayo are never less than convincing in this regard. They deliver R&B ballads, hi-NRG synthpop and EDM, all with a distinctive rhythmic and tonal edge provided by their instruments of choice. The melodies and timbres of kulintang music are a natural fit for all kinds of synthesized dance music—they provide a distinct and welcome organic counterpoint to otherwise sterile electronic production. It’s the kind of instrument-and-genre combination that seems so obvious and natural once you hear it; it’s surprising it hasn’t been done before.

But of course, it hasn’t been done before—Pantayo are the first band to play the kulintang this way. And though they ably show off the range and strengths of the kulintang instruments, their skills as composers of Western pop seem far shakier. Blunt and literal in its execution, the Western half of their musical style is filled with clichés and stylistic quirks that undermine much of the good done by their ambitious mixing of genres. As such, Pantayo’s debut album is both a testament to their ambition, and evidence that they are only at the beginning of their journey. Any future albums, and any future refinement of their sound, will only produce more and more fabulous results.

[5]

Ryo Miyauchi: Pantayo’s self-titled album fits unassumingly with any alternative electronic pop from the past decade, the kind rooted in the comfort of one’s bedroom and its imagination reaching out to multiple musical worlds. I liked the record first as an exploration—rather than an introduction—of kulintang. The ensemble dips into a range of stylistic avenues through their instruments, its metallic tones adapting as foundations of meditative chillout, hypnotic house-pop, and psychedelic R&B, just to name a few. While it lacked consistency, its sprawling nature turned out to be a fascinating feature to hint at some of what was possible.

The ambitions behind the process initially seemed to make up for the actual end result. Though rich and well defined, the songs didn’t feel too unique. The more dissonant ones, like “Taranta,” were more of a standout, or at least more playful than the tracks with a clearer stylistic goal. Returning to it a few more times, though, I realize the success of Pantayo is in how the ensemble seamlessly incorporates kulintang instruments to pop styles I’m already familiar with. It doesn’t have to announce itself to be heard; it can coexist with other popular sounds while forging its own identity. Pantayo doesn’t complicate the status quo. Rather, the record assumes kulintang already established its own place within the contemporary.

[6]

Average: [5.17]

Further Ephemera

Our writers do more than just write for this newsletter! Occasionally, we’ll highlight things we’ve done that we’d love for you to check out.

Still from Glass Shadows (Holly Fisher, 1976)

Our writers do more than just write for this newsletter! Occasionally, we’ll highlight things we’ve done that we’d love for you to check out.

Vanessa Ague interviewed composer and percussionist Matt Evans about his debut solo album, New Topographics, for The Brooklyn Rail. “I've been trying to find sounds that exist mid-crossfade,” Evans says.

The latest issue of Matthew Blackwell’s Tusk is Better than Rumours newsletter features a primer on the works of Matana Roberts. “She creates patchworks of sound made from scraps of oral history, written accounts, and folklore about those women important to her—[Marie Thérèse] Métoyer, her grandmother, herself,” says Blackwell.

Jeff Brown put up an exclusive Bandcamp subscriber release called Eta Aquarids.

Themes / Dances is the name of a new newsletter from Mark Cutler. Its most recent issue featured a review of Ericka Beckman’s You the Better, a work he calls “one of the great films about capital.”

Jesse Dorris talked to multiple architects and designers about PPE for the eleventh dispatch of Interior Design’s COVID-19 coverage.

The 4th issue of Sam Goldner’s newsletter features write-ups on works by artists including Fire-Toolz, bod, Dean Evans, William Eaton, and Twiddle. He also wrote about Final Fantasy VII Remake and included a nice picture of his cat Millie.

Arielle Gordon has a radio show on KPISS.FM called Heavy Ambient Massage. You can listen to the latest episode—which features songs from Kraftwerk, Couch Slut, and Vallendusk—here.

Marshall Gu was a guest writer on Matthew Blackwell’s aforementioned newsletter. He wrote a primer on Philip Glass. “There are very, very few Philip Glass songs that can be described as ‘happy,’” he says. Lovely!

Do you like websites? Raphael Helfand just created a personal one that hosts all his clips. A nice shot of his mug is on there too.

Leah B. Levinson wrote at length about the new Fire-Toolz album, Rainbow Bridge, for her newsletter Happiness Journal. “I could chart the turns the album takes, but to what end? The best way to know it is to be lost in it, to experience it as a conversation in passing, a moment in the process of being lost, the same way we come to know others,” she says. This editor considers it his favorite bit of music writing all year.

Jesse Locke wrote an obituary for Florian Schneider over at FLOOD Magazine. The article features never-before-seen photographs of Kraftwerk’s Ottawa performance in 1975. “Kraftwerk’s contributions to the electronic acceleration of music stretch as vastly as the highways of Germany,” says Locke.

The latest issue of Ryo Miyauchi’s This Side of Japan newsletter includes reviews of the latest Dempagumi.inc album and a 1975 single from Sakura & Ichiro. Regarding the former, Miyauchi states that “this is Dempagumi.inc at their most genuinely human.”

Jordan Reyes wrote a report on Fargo, North Dakota’s noise scene for Bandcamp Daily. “The city boasts one of the more vital and inclusive noise scenes in the United States,” says Reyes. Red Summer, the latest album from ONO, is also out now.

The most recent issue of Mariana Timony’s The Weird Girls Post featured a list of recommendations for Bandcamp Day. There’s also a really great photo of some horses that you need to see. Timony also convinced Substack to allow Bandcamp embeds, so please say thank you.

Jonathan Williger curated a show for Experimental Sound Studio’s The Quarantine Concerts. It’s happening tomorrow, May 12th, and the bill is stacked: Luke Stewart, Ka Baird, Andrew Bernstein, Sarah Hughes, Jax Deluca, and Model Home. Williger also reviewed the new Okkyung Lee album for Pitchfork.

Nick Zanca released a new album called Unguided Tour, which you can grab on Bandcamp.

Still from Subway (Holly Fisher, 1968)

Thank you for reading the fifteenth issue of Tone Glow. We hope all is well. Please wear masks if you go outside… please.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.