Tone Glow 013: Terri Hanlon

An interview with Terri Hanlon + an accompanying mix, album downloads, and our writers panel on Okkyung Lee's 'Yeo-Neun'

Terri Hanlon

Terri Hanlon is an artist from California who primarily creates video art. Black Truffle recently released She’s More Wild…, an LP that gathers archival pieces that she made with David Behrman, Paul DeMarinis, Fern Friedman, and Anne Klingensmith in the early ‘80s at Mills College. Joshua Minsoo Kim and Hanlon spoke on the phone on March 31st to discuss the album, her film Meringue Diplomacy, her collaborators, and more.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Let’s talk about She’s More Wild!

Terri Hanlon: Gosh, what can I tell you! We’re totally thrilled that this whole record is happening. We just got our records from Germany yesterday, so we’re doubly thrilled.

I love the cover. Can you tell me what’s happening there?

I had a background in photography—I studied photography at the San Francisco Art Institute while simultaneously studying in high school. I had a really great education there. I would take press shots—we would do everything ourselves, there was no such thing as hiring a publicist—and we would make our press releases and send pictures out. I think that was the primary reason we first made them. When we made our smaller 45 we put Fern Friedman on the cover of that, and we thought it would be funny if we put another press photo for the album. (laughter).

It’s a great photo, it looks really good!

Thank you! I set those up in our studio, we had a lot of fun doing those.

It seems like you wear a lot of hats, but it’s clear with all your art, from the videos you sent me—Meringue Diplomacy and The Frog in the Pond—and with She’s More Wild, that there’s a performative aspect to them. It’s all very theatrical, fun, and playful. What draws you to that sort of work?

That’s a really good question. My undergraduate degree—my Bachelor of Arts—I got from what is now called the California College of the Arts in Oakland. I started being really hot and driven to do photography. I studied that at the University of New Mexico, which was great because all the great photographers wanted to go down there on vacation. So I got my chops down there, and then I rebelled against the flat surface for a little bit and started doing fabric sculpture, and all kinds of three dimensional work.

Towards the end of my undergraduate education, conceptual art was hitting in a big way, so I shifted over to conceptual art. I was trying to figure out where to go to graduate school because I was having such a good time, and God forbid I go out and get a serious job (laughs). San Francisco State University had just opened up this phenomenal department called Creative Arts Interdisciplinary. I was able to get a work study job in that department assisting the director, Jock Reynolds. It doesn’t sound like a big deal now, but there were only two departments like that in the country at the time—this was around the mid ’70s. There were programs at Yale and San Francisco State, and I knew I wasn’t a Yale type—and so did they (laughter).

So I got into this program and it was phenomenal. You would be in a room with—let’s say this was an art class—maybe ten people in it. Two or three would be dancers, another two or three would be sculptors, another two or three would be painters and, you know, one pervert and poet or something (laughter). It was really amazing and it was a very charged environment. Also, it was so wonderfully inexpensive to live at that point. And no one cared about San Francisco, it was this Dashiell Hammett place at the end of civilization. There were very undeveloped parts of downtown—South of Market. You could easily rent a studio and work part time and live! I had roommates and a great house. My best friend and collaborator lived with me, we were like sisters!

So to answer your question, at that point, sculpture started coming together with the performers I was meeting, the happenings, all this stuff was popping up at once. One of my mentors, Jock Reynolds, had studied with another interesting artist named Robert Watts, who was very active in the Fluxus group. Also, we were in love with those early Robert Wilson pieces, especially the one he did with Philip Glass [Einstein on the Beach]. Using really interesting ways of making sculpture, the objects would be part of the dance or the gestural work.

I think it’s also who you meet and when. When I was working with The Eva Sisters I was hanging out at Mills college, meeting all these great people. They were young and driven like hell, and they were gonna be the next whoever, you know? We were hanging out, going to all these completely unheard of concerts. I had a college friend who I took to a concert at Mills and—this is really high praise—afterwards, she never spoke to me again! (laughter) It was just too far out.

It was a lively environment. You were getting stuff from all angles. I had never really been interested in dance, but working with Deborah Slater I came to understand dance as part of a theatrical gesture. You’ll notice at the end of Meringue Diplomacy there is a really nice dance that goes on, a very simple dance, choreographed by Carol Clements. It’s all part and parcel of what I think of as my brand. (laughter).

Promotional still of Terri Hanlon

How would you describe your brand?

Oh, God… well it’s interesting that you ask that. As I was mentioning Meringue Diplomacy—I feel like the term, it’s not quite right—but I’d say it’s a “fictional documentary,” because it really is one! Every fact is substantiated in Meringue Diplomacy except one: I do not have solid evidence that Carême was gay, but after copious research and the way he wrote about the head of the Russian imperial household, my San Francisco gaydar told me he must be! The next piece I’m working on is going to be really fictional because I think for the first time I’m going to completely build a character from scratch. Up until now I’ve found characters who really inspired me, like Carême, but now I have this idea that I want to take to the next step, building a character from scratch so I can really put all the aspects I want together.

With Meringue Diplomacy, the fact that the story is true—people have a hard time believing it but it was true, that Carême rose to such great heights. And of course it’s not in style to do work like that. God help you if you do something about a guy who worked for aristocrats. That is seriously out of style now. But I didn’t care, I thought it was such an interesting story. The more traditional doc I did after Meringue Diplomacy, The Frog in the Pond, I knew I would have a hard time getting that shown. It took two years to get it shown because, well, an elderly patrician white lady who is not a celebrity on screen? Are you kidding me? No! (laughter). Not going to be easy to get shown. But needless to say I’m delighted I did it for a lot of reasons.

For one reason, it was a great to visit my inspiration as a young artist. I had known Nina Van Rensselaer since I was twelve, and loved visiting her and seeing her ever-evolving collection. I would say my brand in general is Fictional Documentary. I love facts, and I love fiction. I did all my own research on Carême pre internet: going to libraries in New York and Paris, copying pictures from microfiche, etc. I really enjoy research. A professor in the Sociology Department at Columbia vetted my research for Meringue Diplomacy and made it required viewing for her class; my facts were that accurate. I was very proud of that.

You mentioned that you brought your friend to a concert and that they never spoke to you afterwards. Do you remember what happened at that concert?

(laughs). You know, darn it, I can’t remember exactly who was performing that night. It could have been someone with homemade instruments, or someone throwing stuff across the stage. I can’t remember, but I must have been thinking, “Wow, this must be powerful stuff if this woman won’t speak to me anymore.” It was great! I remember going to this one concert, Takehisa Kosugi, and he did this piece one night that totally blew me away. The piece consisted of him putting a piece of paper that he had balled up on a mic—it was out of this fucking world! It was amazing! You didn’t see or hear things like that anywhere else! It sounds more familiar today, but back then it was really, really wild. On both sides of the bay—Mills in Oakland, and in San Francisco—it was great, a very prolific time for people.

It was a very energizing, inspiring time for you and other artists. After having seen these other performances, what did you learn that you could do with your own art?

That’s deep! (laughter). The conceptual art was kind of the winner. It was also like studying philosophy. You really had to think when you saw these pieces. Let’s remember that video was just starting out as a portable medium at that point. Of course I had also seen Nam June Paik’s work. I thought he was just out of this world. And at the same time I was working with Fern and we were playing with words and I was working with sound. I started really falling in love with air waves.

Also, performance art is really hard work. It’s really hard physical labor. I had a good friend who was very active in the performance art scene who had really damaged her back, and I’m seeing all this and am thinking that I want to do something I can do in the long run. That’s when I started doing video, because it kind of fulfilled all my needs: I could work with sculpture and props, I love working with teams of people, and I can work with something that can be sent over the airwaves. That was something I really fell in love with. I thought, “Oh my god! This is such an amazing thing!”

In high school I was in love with the technology of the still camera. I got my father—unbeknownst to him, the poor guy he had no idea—(laughter) to buy me a hot camera, a Leica M4 with a slightly wide angle lens. It’s gorgeous, and I still have it. I knew everything you could possibly know about a camera, I was like possessed. And then, to come to this time where, holy shit, you can be a part of that! The video camera may weigh fifty pounds, but you can still carry it around and shoot on location! That’s how I decided to really become focused on video.

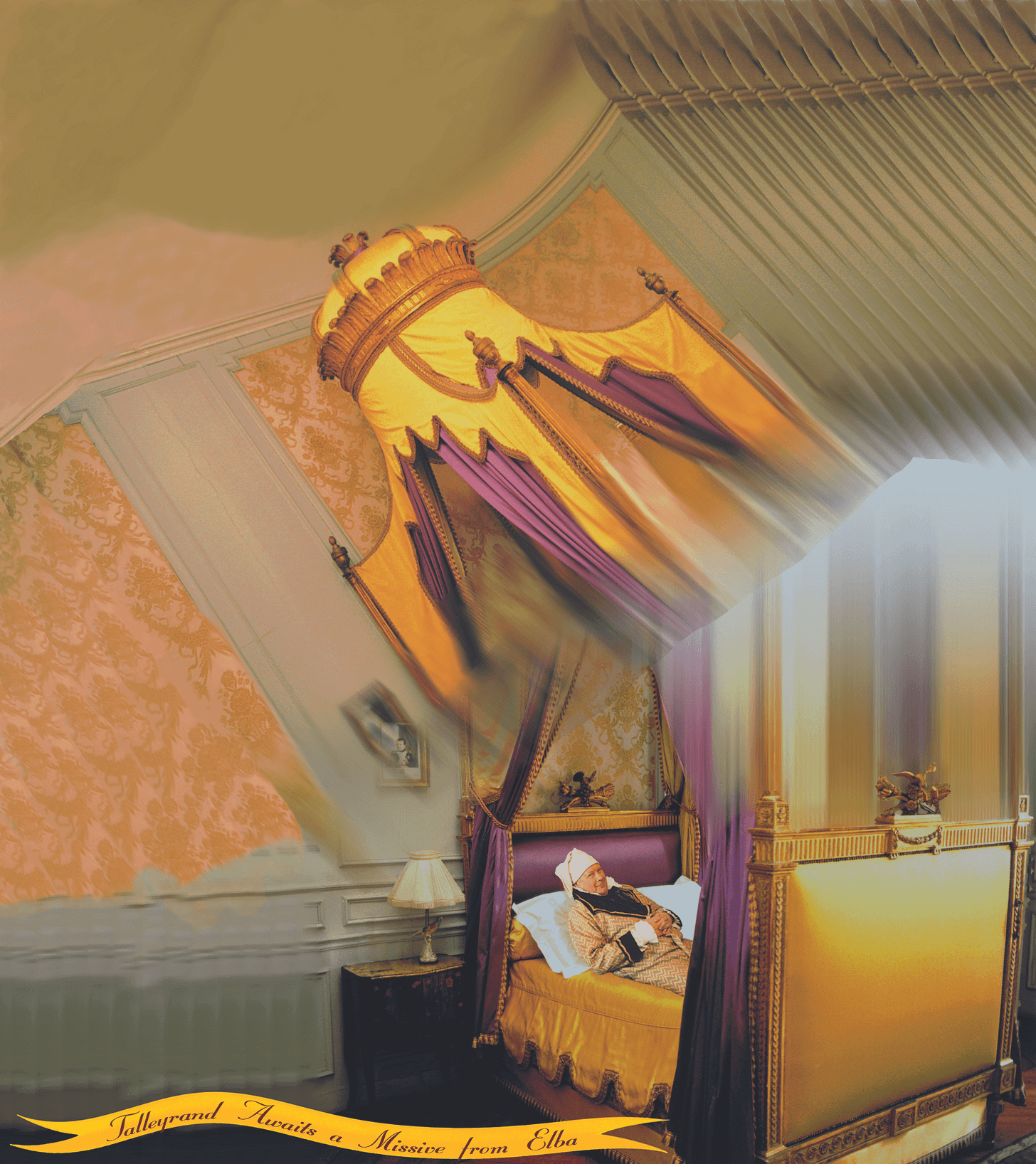

Jacques Bekaert as Talleyrand in Meringue Diplomacy (2010)

It’s funny—you learned so much about using the camera, yet it was so unexpected when you sent me Meringue Diplomacy that you told me to watch it on a small screen, like on a cell phone or a tablet. Usually people who do video work would never say something like that! What’s the appeal to you of watching these works on small screens?

Everybody thinks I’m completely insane when I say that, so you’ve got a point there. (laughter).The thing is, all my life I’ve been in love with Persian miniatures. They’re just so beautiful, and they’re always small, they’re always of a small size. To me, the cell phone, it’s my digital Persian miniature. That’s one reason. The other reason is that it simply looks better. As I mentioned on UbuWeb, this piece was made at the tail end of the lo-def era. I worked on it for 15 years and as soon as I finished it, all these gorgeous high-def cameras were coming out. It’s quite grainy, and when you have to compress it the way I did for UbuWeb, it’s just not going to look as good on a full computer screen.

So that’s just me, it’s just my pet peeve. But we have this running joke at night—David Behrman and I live in the country, which was a big change since we lived in Tribeca for forty years—after dinner he might read and I would say I would do a little bit of light streaming. And we have a big monitor, but I would always watch everything on my cell phone. I’ve seen so many pieces of art on my cell phone! (laughter). I like the intimacy of it too, you know!

I feel you. I’ve definitely watched movies from the comfort of my bed on my cell phone right next to me. It’s very cozy. At that point it’s easier for me to not be distracted as well. If I watch it on a computer screen, for example, I never feel as comfortable and can be easily distracted.

Yeah, it feels like you should be working. It feels like you’re fucking off or something, even if you’ve worked all day and you’re just taking an hour to watch something, you know? It’s very interesting. Also, I have to admit, when it was time for me to get a real job, one of my first jobs in New York in the real world was working for this really early silicon valley company. It was so early that there was a limited color palette. We had to hand color images over black and white with that, and as you can imagine, it was not easy. They were just starting to develop these digital graphic applications. You see those on some of my really early videos.

I was the person who went into the art departments of major corporations like Colgate-Palmolive and instructed the artist to put down their pencil and pick up the digital pen, or else they would soon be out of a job. It was very difficult. I was 25 and some of the artists were in their 40s or 50s . Sometimes they would cry. I had to be part therapist, part artist, and part educator. Also, around this time I was fortunate to work with Jonathan Cohen, a brilliant software designer. He made code from scratch to animate my video for “You Pay Rent on Your Brain,” as well as several other pieces.

This is going to sound really corny, and I apologize, but I used to sit in the office and fantasize—not about George Clooney, because he was just a young man (laughter)—I would fantasize that someday I would be able to hold these moving pictures in my hand. I’m not just making that up, it’s a true story! And I think a lot of people were hoping for that. To have this come true, is like… streaming totally rocks. I’m sorry, it’s so hard for most people like me to get on these websites that everybody knows about but, you know. I just think streaming is out of this world. It’s really great. I know that’s like saying, “Oh, I think the staple is really great.” (laughter). But, y’know, like—

It’s your work being put out there, it’s always going to feel good, for sure.

Exactly! I remember how excited I was when I would get a little piece in a film festival and PBS would pick it up. I would go to parties and someone would come up to me and say, “I saw your piece on Canadian television.” I’d never authorized that, I would be a little pissed, but I was still happy that people were seeing it!

It’s a good feeling when your work is out there and people have seen it, and people recognize you.

Now the problem is that there is so much media, which also makes it harder to get your work shown. I had this assistant a while ago—she was so cute, she said, “Well yeah, everybody’s a video artist now.” And I was like, “That’s interesting, you think so, huh?” (laughter). Interesting idea. But you know, everybody is putting their cats on YouTube, it’s part of this era. I’m also very excited about Instagram as a new TV frontier.

Earlier we still had the NEA where individual artists could apply. We did get some funds for She’s More Wild from them, but that all collapsed. Then we had to go through… I never learned how to kiss up, I never made it in that environment, of aligning yourself with a non-profit organization. That never worked for me. I worked with incredible people who I paid with my cooking. I basically did barter!

What’s the recipe or dish that you made that people enjoyed the most?

Oh my God! That’s a tough one to answer. I did so much cooking. What were some of my specialties… I know I made a very good chocolate mousse. I inherited some plates, because I was the only girl in the family. I would do the whole mise en scène: I would get out the 19th century limoges plates, poach a salmon and put garnish on it. It was fun.

I was very honest with my collaborators, two wonderful dancers, Eric Barsness and Carol Clements, the brilliant cameraman Howard Grossman, the fabulous composer Frankie Mann. I would say, “Look, I really don’t have any money, but you’re going to eat well.” And I made that come true! I can cook just about anything! Leg of lamb, a lot of French cuisine, you name it.

Is there a favorite dish you like to make now?

You know what? I’m trying not to get into a rut. I started to feel like… you hit a certain age and you feel like you’ve been cooking the same dishes for twenty years. It’s interesting, living in the country feels like growing up in California again. There wasn’t that much going on in California when I was growing up in the ’60s. Well, there was, but I didn’t know about it. We did a lot of cooking. When I was dating David, we made up after our first fight, when David invited me to the Alice Waters restaurant Chez Panisse. That’s what life was like in California. He was a smart guy by the way—David—still is. (laughter).

Now I’m working my way through the Ottolenghi books, which can be quite a lot of work. I bought one recently called Ottolenghi Simple, which is fairly simple. But it’s delicious, it’s all really really good. I make chicken with preserved lemon, that’s good. I’m trying to be kind of healthy.

David Behrman and Fern Friedman, early ‘80s

What I really appreciate about your work, and even about the conversations we’ve had, is how much you care about collaboration and how much other people and their lives mean to you. You’ve been friends with Fern for a long time. Was Fern at San Francisco State as well, or did you two meet after that?

I met Fern in that interdisciplinary graduate program I was telling you about. We became fast friends. When I moved to New York and got busy, she also got very busy and became a single mother. As happens in adult life, we fell out of touch. This album has brought us back together which has been really great. We’ve been talking a lot. I wrote Oren Ambarchi a letter thanking him. And Anne Klingensmith: David and I lived with Anne and Paul DeMarinis right around the time we made She’s More Wild. Everyone goes their separate ways, same thing with Anne. Paul I’ve spoken to occasionally but Anne I haven’t spoken to in a long time. So it’s great, it’s truly good. That’s really important in the arts, because, are you going to make a killing? Probably not. (laughter). So you better be enjoying it, enjoying the work and the people you work with.

I keep mentioning these guys, but Carol Clements and Eric Barsness, I’ve worked with them on two pieces, and it was just so much fun! I would involve the performer Massimo Iacoboni in my projects. He first came to New York City with an Italian avant-garde theater group and never left. Our jaws would hurt, there would be so much laughing when we were shooting these scenes, even when they were supposed to be serious. I can’t help making funny works. I think this next piece will have humor, but I think it’s going to have a lot of poignancy too. We’ll see.

You and Fern go way back, what is a memory of you two that you cherish?

She was a few years older than me. It’s interesting, and I hardly ever thought about it but my mother had a baby who only lived for two weeks and then died. That would have been my older sister! Of course, I never got to meet her. Fern would have been just slightly older than that sister. We really hit it off. She had a little more experience than me, she was a little older, a little wiser. We would go out and have great art talks and she would say things like, “You know, Terri, you’re in your 20s now, you really don’t need to be wearing a ponytail and braids all the time.” (laughter). She was trying to help me out! She would always say stuff like that.

We just had such great times. We would hang out at the cinematheque and the San Francisco Art Institute. We would have great parties. We had been spending a fair amount of time at Mills College at the Center for Contemporary Music, so I made a stamp and renamed our house The Center for Contemporary Talk. (laughter). We would have wonderful parties there.

Fern and I had such an intellectual rapport. Talking and developing ideas with her was really fun. She was serious, but she also had a sense of humor. That’s another thing about the art world, humor is not that popular.

I know, it’s not! It’s annoying!

I remember coming to New York and everyone was like, “Humor? Really?” I don’t know why Lovely Music turned down our album, but I’m sure that was one reason. It might not have been considered serious enough.

I have to say one more thing about that period versus this period. When our little record came out—this just popped into my mind the other day, I totally forgot about it—we made an agreement with this distribution company. This distribution company put out a little pamphlet, and in that pamphlet—I got very angry—they only gave David and Paul credit for this project! And I got so mad that I had a lawyer, who knew nothing about entertainment law, send this joker a letter. It was like a cease and desist. It said, “If you ever publish another catalogue and don’t credit us, I’m suing you.” I got this irate letter back from them—I don’t know if I still have it—and it was totally without apology and didn’t say anything like, “I’m sorry, we’ll fix that.” They responded, “Do you realize how lucky you are I’m doing this,” (laughs) the whole thing was just absolutely appalling! So anyways there’s a little story about what it used to be like, so I’m really happy to say that things have changed. That’s a very wonderful feeling.

David Behrman and Terri Hanlon, 1978

When did you first meet David? Oh, and what was your first date? I’m curious about both of those things.

Well, there are a few funny stories here. I’ll start out with how we met. I met David when I was working at a guest studio access program at Mills College, where students would get real life studio experience working with outside clients. I was then designing sound for the Eva Sisters pieces in addition to performing and conceptualizing content. He was sharing the directorship for the Center for Contemporary Music with Robert Ashley. It was a sweet gig for them, because they only had to commit themselves to about four or five months a year each for this job. I probably just met David in the hallways at that point. One of the graduate students who was helping me with The Eva Sisters’ sound design was a composer named Fast Forward. He was great, we were friends—he’s this British guy. And he said to me one day in his fine British accent, “You know, there is someone here that—and he’s kind of weird, but—you might want to invite him to San Francisco State.” Part of my job at San Francisco State was not only to assist the director of the program, but to also run a lecture series. And I had no shame, I would call anybody and ask if they’d like to come. So I invited David to that series, and he was very kind and said, “Sure, I’ll do it.” The pay was a whopping $25 to $50.

So he came over and I thought he was great, I thought his work was pretty amazing. However, he had a very nice girlfriend that I knew, so that was that. Then, a couple of years later—I think I maybe finished with the graduate program, or was about to be finished—I got a call from a woman named Suzanne Hellmuth, who was helping her partner out, Jock Reynolds. They ran an art gallery called 80 Langton Street in San Francisco. She called me and said, “Terri, I hate to bother you, but I’m going into labor, and I’ve got this guy coming out from New York for a residency. Can you take care of this for me? Can you be the administrator for the residency?” And what was I going to say, that I’m too busy? And, of course the guy was David Behrman so I said, “Oh, absolutely! I can squeeze that into my schedule.”

So David came out and I spent a week with him, and working, just doing things like making sure the door was closed at the end of the day. It wasn’t a very tough job. We would go out, and everybody loved David, people were always throwing him parties. That’s when I fell for him, and I think vice versa. After that we started to date. I think our first date was that week. David later told me that one reason he fell for me was that I was the first woman he ever met who owned her own voltmeter. (laughter).

You can see that I’m okay with talking, you’re not going to run into a long silence with me. I’ve always been this way, I’m half Italian, half Irish, so I can talk. So all my friends got together and for what was maybe our first date, we were sent to this communal restaurant in South of Market where you were not allowed to speak. So everyone placed bets on me, that I couldn’t get through it. And I did get through it! And a lot of people lost money that night. (laughter).

David, I thought he was hilarious, he would get off the plane from New York and he would take a big, deep breath of air and say, “Oh, God, this air!” And I’d say, “Oh, snap out of it!” When we were first married we were bicoastal for a couple of years. Some people think I developed that word’s common usage because a friend was a cartoonist for the New Yorker, and he started making cartoons about being bicoastal after we went over to his apartment one night, and I mentioned we were bicoastal and then you heard this word being used more and more… so that’s all I’m going to say about that! (laughter).

Anyway, we were bicoastal, but that got to be hard. It was really weird, like, was the carton of milk in the fridge in New York, or was it in the fridge in San Francisco? (laughs). We ended up moving to New York, to David’s bachelor pad that he bought for like $20 in the 70s. It was the building that Mimi Johnson and Robert Ashley were in, so they all got there around the same time before Tribeca was called Tribeca. David originally lived there with roommate writer/composer Jacques Bekaert. So that’s the story!

Terri Hanlon, mid ‘80s

Thanks for sharing all of that! That was fun! You two have been together a long time and created your own individual works. Do you feel there is a shared influence that goes back and forth in regards to the art that you two make?

I am always driven by experimental music in my work, in my video. I have been really lucky to work with many fine composers: Frankie Mann, Jacques Bekaert, Jon Gibson, Barbara Held, John King, Laetitia Sonami, Gisburg, Lenny Pickett, Rhys Chatham. I treasure Eric Barsnes’s singing as well as his choreography and dancing. I always find that I love to use some of David’s music in my work. As far as the other way around, a little bit, David did this piece called Useful Information that was more of a sociologically based piece that I think has my influence in it. I think David is very much in his world, computing, designing, as well as being a wonderful, highly trained musician—that keeps him pretty busy.

I think one of the reasons our relationship has lasted so long is because he is from a very theatrical family. His father was a playwright—I’m David’s third wife, so unfortunately I never got to meet my father-in-law. I heard he was hilarious, that he was a really funny guy, and people have said I’m pretty funny. I think David really appreciates my humor on a daily basis. That helps a lot for the long term. It’s crucial.

It’s essential for any long term relationship, for sure.

I think so. Unless both people are deadly serious and that’s the way they want to be all the time, then that’s the other way to go I guess (laughter).

We’ve talked this long already and we haven’t even touched on the album! How did the idea for She’s More Wild start out? What were the goals and ambitions for these works?

Basically, as I’ve been mentioning, the Bay Area was just so open at that point. I think it was great for David because things were quite serious in New York, and everyone did what they did in quite a serious way, and he was from a very serious musical and artistic family. His uncle was Jascha Heifetz, we’re talking pretty serious stuff here! So in California it was like a ticket to funland! (laughter). He could experiment and it wouldn’t necessarily get back home. It’s hilarious to say, but things were different then, there was no internet. If people weren’t writing about something, it might have just stayed local. So David and Paul were very open to experimentation. They respected Fern and me, they knew we were quite serious about what we were doing, so that created a bond.

When we lived with Anne Klingensmith, everybody was just blown away by her. She was a phenomenal singer, she really mastered the art of the Indian singing style. We all really wanted to work together. We were just tossing out ideas. My ideas are coming from being a third generation Californian, and I would spend time near Donner Pass, go to Lake Tahoe. My grandparents lived through the great earthquake, but my maternal grandparents had to live in a park for a year in North Beach. They were young and had several kids. No one was killed but they escaped their destroyed home with a mattress and a sewing machine. I grew up with the specter of natural disaster in my roots. Adults would always be like, “You don’t want to put a bookshelf above your bed, remember the great earthquake!” (laughs). That was all just bubbling in my psyche. I also studied sociology, so that was one idea that came up. Fern was feeding in ideas. She was studying linguistics and writing. All these things were getting mixed in together. And then I picked up a copy of The Girl of the Golden West, which isn’t the greatest opera in the world, but it had some interesting characters like this girl who works at a bar. So I thought, “Well, we could do that.”

Everybody brought things to it. It was a very long time ago. These guys, Paul and David, they’ve done phenomenal things with art and technology, but they also happen to be really good musicians. Paul just came up with the tune for “Cannibal Cowgirl,” and he and David ended up playing piano with four hands at some point. It was all these things coming together at different points.

How did you decide on the specific topics covered on the album? I know some of it was inspired by the opera, but what about “I Feel Like A Martian” or “Japanese Disease”, where you talk about white people obsessed with Japanese culture? Where did these ideas spring from and why did you want to cover them in your work? Or even “Archetypal Unitized Seminar”?

As I mentioned, I had taken a few sociology classes and I think it led me—and it still does to this day—to a great interest in the study of the human being: how humans behave and what they do. For the original album that Lovely Music rejected, it did not have the stories on it, it just had the music. I thought it would be a fuller experience if we put the stories on the record too, just to fill it out. Then we had these other pieces we made. “Japanese Disease” for me was very much an examination of 80s New York City. I’ve always been a foodie—that’s what we did in California—and all of a sudden there went from one or two Japanese restaurants to zillions of Japanese restaurants. You could just see it, It was amazing how interested people became. I had to write about that. The whole love of Japanese design and everything, I thought that was the way I would chronicle it.

With “Archetypal Unitized Seminar,” I frankly couldn’t wait to get out of California because, to me, all they did was exercise. It was all about exercise and nutrition! Also, encounter groups and The Esalen Institute! You pay rent on your brain, you know? I remember when I went to my high school, my poor parents were born in like 1907 and 1908, so they were old parents for their age group. They sent me to a convent boarding school in Marin County. You can imagine in 1971 San Francisco when things were getting fun, I was under lock and key. California life was pretty wild, but in some ways it wasn’t. All the kids that were put into the school thought I was from the east coast because I was talking too fast! (laughter). They said, “You’re talking too fast, you can’t be from California!” I felt like I had been wrongly dropped out of the stratosphere into California.

I recently learned that my great uncle, Charles Hanlon, was the entertainment lawyer for the Ziegfeld Follies and was bicoastal in the early part of the 20th century. He must have felt the same way about California!

What was the goal of the video aspect of this project? What was it like creating it?

That was the first time I used video on stage with performance art. I had a great time making the tape for that. All it was was one little monitor that showed tapes, but we were performing in other small spaces so it was visible. I did all my research at The National Film Archives and I had a great time. You can find amazing stuff—the one shot of Anne Klingensmith, the tape was from a film called She’s Wild, which I named the piece after. It was amazing, it was very inexpensive to buy the footage, it was really old. It gave that piece a little more flavor of what we were dealing with. I loved researching down there. Sadly, a lot of archival footage got destroyed in a really bad fire at the National Film Archives. A lot of it is gone now.

For the last performance art piece I did, This Setup No Picnic, with Frankie Mann, Fern Friedman and Julie Lifton, I got a kit from Edmund Scientific, that was basically two lenses. It was low quality but it was really fun because you could make a big projector out of a cardboard box and a couple of lenses. That was the next step. From there I went directly into making tapes and working on video. That, again, was for distribution. It was to make something that more people could potentially see compared to the performance art gigs that were tough and grueling, where you’d get an audience of 2 or 200 and would never know what was going to happen.

Three nuns in a tub, (L-R): Julie Lifton, Terri Hanlon, and Sharon Ludtke from Inversion of Solitude (1993)

What advice would you give to younger artists? What do you think would be helpful for them to know?

Don’t be discouraged. Don’t think that what you’re doing is not going to be seen. Follow what you really believe in. That’s the main piece of advice I would give, because it’s very easy to be discouraged now. Don’t do it thinking that if you don’t have a viewership of a million that it’s not good, because of course it's good! And, hang in there. That’s my biggest piece of advice. (laughs).

And, if it takes fifteen years to make a piece, then spend fifteen years on it! I’m a big Proust fan. The guy has only one big serious book. I made that decision in my work, and people would laugh at me and say, “Are you ever gonna finish this?” And I would say, “Yeah, I’m gonna finish it! It just takes time because I wanted B-roll from France.” It took a lot of time and money. Things take as long as they’re going to take, period. That’s all there is to it.

Is there anything else that you’d like to say?

I used to watch Harvey Weinstein walk by my studio with his yes men when I lived in Tribeca. It was a sight to see. This intimidating bully was always trailed by four 25 year old men with notebooks. I’ll never forget that sight. I think things have really opened up. When I was coming up, doors weren’t locked for you as a woman, it’s just that they weren’t open. That was my experience. I wasn’t told that I couldn’t do something, but when I did, I and the majority of my colleagues were always being overlooked. I heard a music patron say, I swear to God, “Well you know there really aren’t many women composers.” I was just about to— (pauses). That was really appalling. Knowing a lot of really great women composers whose careers were killed or damaged by this kind of neanderthal thinking. It was not pretty and I’m really happy that things are changing now.

She’s More Wild… is available at Forced Exposure and Kompakt.

Tone Glow Mix

Every now and then, artists will provide a mix personally made for Tone Glow. Mixes will always be available for streaming and download.

This mix is work that David Behrman and Terri Hanlon collaborated on over the past 40 years.

Fern Friedman as Doctor Gene Poole: from the radio play Sound Solutions, a collaborative project by The Eva Sisters (Fern Friedman, Deborah Slater and Terri Hanlon) and David Behrman.

Dr. Poole is interacting with David Behrman’s interactive “Sibilant SSS” program. Portions of this play were used in Looking Past the Future performed at the Marina Theater at Fort Mason, San Francisco. (Dr. Gene Poole: Fern Friedman). 1979; 0 to 2’ 49

I Love You In Spite of the Pain (2002) Music by David Behrman for Terri Hanlon’s video screened in the Post-Glamour Summit, Performance/Video Festival at New Langton Arts, San Francisco. Produced by Johanna Poethig as a response to 9/11. 2002; 2’ 49 to 6’ 12

Letter From S. N. Behrman to Siegfried Sassoon, August 22, 1939 ; Excerpt from My Dear Siegfried CD, XI Records

Maria Ludovici, text reading; Thomas Buckner, vocals; David Behrman, electronics. 2005; 6’ 12 to 16’ 06

Meringue Diplomacy: Eric Barsness as Antoine Carême sings “The Love Song” to Mueller, the head of the Imperial Russian Household. Mueller is played by Joseph Hannan. Terri Hanlon, lyrics; Modest Mussorgsky, tune; David Behrman, piano. 2010; 16’ 06 to 20’ 11

—Terri Hanlon & David Behrman

Download links: FLAC | MP3

Streaming link: YouTube

Download Corner

Every issue, Tone Glow provides download links to older, obscure albums that we believe deserve highlighting. Each download will be accompanied by a brief description of the album. Artists and labels can contact Tone Glow if you would like to see download links removed.

Trevor Wishart - Journey Into Space (self-released, 1973)

The liner notes for Journey Into Space describe the album as an “allegorical journey of a man towards self-realisation.” The reissue by Paradigm Discs splits the 79-minute piece into three movements, and their titles (“Birth Dream,” “Journey,” and “Arrival”) readily guide the listener into thinking about the work with this loose narrative in mind. Even then, Trevor Wishart doesn’t make it particularly difficult to latch onto some semblance of structure—some of these sounds are fairly on the nose. “Birth Dream” features noises that could signal some sort of “beginning”: a rhythmic sound akin to someone snoring, chimes that sometimes recall music box twinkles, some gooey muck that makes me think of primordial soup and womb sounds, and—for good measure—a good ol’ crying baby.

“Journey” begins with an even more obvious sense of storytelling: a man wakes up, puts on clothes, and starts his car to head to work. We then hear a countdown and the sound of a rocket launch, leading the album into more inscrutable territories. It’s this—a traversal of drones and free improvisation and musique concrète—that signify our emergence into space, into the unknown. The music strives to accomplish—in a rather accessible manner—a goal that Wishart had for his art:

I was interested in the idea of creativity from a political point of view. I felt that by creating things, people would learn that they can have an influence on the world, that they don’t have to just do the things that they’re told to do, or even to do things in the way you’re supposed to do them. You can actually make something yourself.

It’s a fun way of thinking about experimental art and its utility beyond mere aesthetic pleasure, but I’ve found a different way in which Journey Into Space has proven meaningful to me. My life has been one of relatively high guardedness wherein decisions are constantly labored over and the fear of not being able to control my future is rather daunting. There’s a contentment that Wishart provides here with his melange of electroacoustics, and it only occurs because of the general narrative underlying the whole record.

The sounds we hear during the album’s second half aren’t dissimilar to various avant-garde records of its time or kind, but I’m led to think about the discernability of each sound and how they come together in a swirling, quasi-unpredictable manner. Life comes at you with unexpected twists, but it’s only in stepping outside of your own little bubble that you can find yourself like the metaphorical spaceman who’s moved beyond the comforts and confines of his home—in one sense, he’s free. Even more, so much of this “new world” is familiar and identifiable—a personal reminder that much of my previous life experiences, be they good or bad, help me with future ones. Wishart’s goal may have been for people to see that they can influence the world, but that always has to start with an understanding that you, in some small way, can impact your own life too. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Download links: FLAC | MP3

Purchase Journey Into Space on the Paradigm Discs Bandcamp page.

Read an essay on the album by Nicolas Marty here.

Nicolas Collins - Let the State Make the Selection (Lovely Music, 1984)

The son of architectural historians, Nicolas Collins was drawn to experimental music after hearing Alvin Lucier’s I Am Sitting in a Room in the composer-cum-professor’s course at Wesleyan, fascinated with its handling of music via architectural acoustics. Collins eventually created what he calls the “backwards electric guitar,” which, among other things, finds the pickup on the instrument connected to the output of a small amplifier.

Three of his early pieces appear on Let the State Make the Selection. “A Letter from My Uncle” features an ensemble (comprised of Susan Lyall, Robert Poss, and Susan Tallman) feeding various sounds into their modified guitars and bass. Amusingly, the track begins with the sort of glitchiness that one may readily associate with his 1992 album It Was a Dark and Stormy Night. The track unfurls differently thereafter: screeches and scrapes, siren-like noise, reverberant recitation of text. Moments of beauty occasionally arise in the droning murk, but it’s primarily this convergence of lethargy and spontaneity that makes the piece so transfixing.

“A Clearing of Deadness at One Hoarse Pool” is the result of a real-time recreation of a sound installation housed in an empty swimming pool. While similar to “Letter,” the atmosphere here is far more ominous—it’s defined by a sustained and unrelenting drone whose every clang and tone submerses the listener in its massive soundscape. “Vaya Con Dios” is the grimmest of all, with a scattershot assemblage of sound bytes from Ronald Reagan and separate performances of the titular song by Julie London, Slim Whitman, and the Andrews Sisters. Every now and then, one can parse specific words and phrases, but the frenetic nature of the piece and the weaving of these samples is enough to convey the hypocrisy and horror of Reagan’s support of anti-communist regimes during his presidency. While Collins’s exploration of sound is interesting in and of itself, it’s exciting to see a composition that matches the unsettling nature of his music with a befitting message. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Download links: FLAC | MP3

Download many other albums and recordings from Nicolas Collins on his website.

Those wanting to learn about Nicolas Collins and his music should read an essay he wrote titled A Brief History of the ‘Backwards Electric Guitar’.

Peter Gordon - Leningrad Xpress (New Tone Records, 1990)

Peter Gordon’s 1990 album, Leningrad Xpress, is titled after a midnight train ride he took from Berlin to Warsaw that saw him seeking out his ancestors. “In the midst of looking for a Europe of the past, I discovered a new Europe being born,” he writes. “This is the Europe of the future, where ideas and people move freely in all directions.” Perhaps that’s what’s most heartening about all of Peter Gordon’s music, how so much of it is suffused with joyfulness and wonder.

As with all his albums, Gordon works primarily in pop contexts, and the title track kicks off the album with a bit of minimalism-inspired jazz, something like a more robust and endearing Penguin Cafe Orchestra (a brief, midtrack eruption of horns elevates the piece). The eleven tracks here were all meant to soundtrack different dance and theater works, explaining why the album sounds more diverse than the bulk of Gordon’s discography. They all cohere, though, given the boisterousness that characterizes every track.

Still, what shines through more than anything is what Gordon hinted at in the aforementioned quote: new possibilities existed, and they did so through collaboration. Looking at the liner notes while listening to these songs becomes a surprisingly endearing act, not least because it reinforces this notion that all this is only possible from collectively striving. “In the Fields” has searing drones, trumpet fanfare, and the occasional sound of a Jew’s harp. “Woyzeck’s Dream” has operatic vocalizing and throat singing over dramatic, stately piano. “Inside the Nuclear Power Plant” has percussion that makes one think of pickaxes, and it’s Julius Eastman’s voice that triumphs over the track in theatrical fashion. There’s a lot on Leningrad Xpress; it’s brimming with life. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Download links have been removed upon request.

Writers Panel

Every issue, Tone Glow has a panel of writers share brief thoughts on an album and assign it a score between 0 and 10. This section of the website is inspired by The Singles Jukebox.

Okkyung Lee - Yeo-Neun (Shelter Press, 2020)

Press Release info: Yeo-Neun loosely translates to the gesture of an opening in Korean, presenting window into the poetic multiplicity that rests at the album’s core. Balanced at the outer reaches of Lee’s radically forward thinking creative process, its 10 discrete works are born of the ambient displacement of musician’s life; intimate melodic constructions and deconstructions that traces their roots across the last 30 years, from her early days spent away from home studying the cello in Seoul and Boston, to her subsequent move to New York and the nomadism of a near endless routine of tours. At its foundation, lay glimpses of a once melancholic teen, traces of the sentimentality and sensitivity (감성 / Gahmsung) that underpins the Korean popular music of Lee’s youth, and an artist for whom the notions of time, place, and home have become increasingly complex.

Elegantly binding modern classical composition and freely improvised music with the emotive drama of Korean traditional music and popular ballads, the expanse of Yeo-Neun pushes toward the palpably unknown, as radical for what it is and does, as it for its approachability. In Lee’s hands, carried by a body of composition that rests beyond the prescriptive boundaries of culture, genre, geography, and time, a vision of the experimental avant-garde emerges as a music of experience, humanity, and life. Meandering melodies, from the deceptively simple to the tonally and structurally complex, slowly evolve and fall from view, the harp, piano, and bass forming an airy, liminal non-place, through which Lee’s cello and unplaceable memories freely drift.

You can purchase Yeo-Neun on Bandcamp.

Samuel McLemore: After debuting on Tzadik and spending well over a decade mining the depths of free improv and the avant-garde, Okkyung Lee—positioned uniquely as the undisputed star of the modern cello—steps into the realm of easy-listening composition with Yeo-Neun. The Yeo-Neun Quartet, assembled by Lee first in 2016 but on record for the first time here, surrounds her with musicians of not only equal skill, but of similar backgrounds: their combined credits range from experimental jazz ensembles to fusion folk groups and fellowships at Berklee. Inspired equally by television soundtracks and romantic string quartets, Yeo-Neun sees the entire ensemble tackling simple, straightforward compositions with the panache and verve expected of their history. Buoyed by their impeccable talents, Lee’s cello is the heart of each piece. Piano (Jacob Sacks) and harp (Maeve Gilchrist) play rhythmic melodic lines, in pairs or singularly, while the bass (Eivind Opsvik) plays simple droning accompaniments.

Framed in this ensemble, Lee virtuosically plays the full range of tonal possibilities available to the cello, from simple melodic lines to flourishes of extended technique, but never lets any approach dominate for too long. This can sometimes work against the material’s strengths, which are often at their greatest when a rupture appears between the relatively restrained ensemble and the wild cello (hear how it resembles a squirrel chattering up a tree on “one bright lazy sunday afternoon”) rather than when all the players are perfectly in sync. But it’s clear that’s not where Lee’s heart is with this project. The trio of tracks named after Korean ballads belie her goal to make simple, accessible, comforting music. Tasteful and unobtrusive, gorgeous but a little sad, Yeo-Neun is much like the way we always remember pop songs from our youth.

[6]

Ryo Miyauchi: Okkyung Lee lets the light in once Yeo-Neun begins. Though a cellist, the harp sings the most pronounced out of Lee’s ensemble in the first two tracks, and the tender music sets a homely scene as promised by the windowsill depicted on the cover. That said, it’s when Lee disrupts that very notion of agreement and intimate peace that Yeo-Neun becomes a record of its own. The madness arrives early in the highlight “Another Old Story (옛날이야기),” where the dance goes awry and the ensemble tumbles into the most obtuse shapes. Elsewhere, Lee commits the disruption herself through her cello. The instrument’s jagged scribble wrestles with the stately harp in “The Longest Morning” while the pianos, too, collapse due to the friction; it resists a moment of reflection with a sob and a moan in “Facing Your Shadow.” It’s the most stubborn thing you’ll hear throughout the album, hardly complying to become one with the group. But that hard-headed attitude perhaps illuminates Lee’s relationship with the cello that has stuck around with her thick and thin.

[6]

Vanessa Ague: Cellist Okkyung Lee is known for pushing her instrument to the outermost limits of its technical capabilities, but with Yeo-Neun, both the title of her latest album and the name of her quartet, she channels explosive sonic exploration into a more conventional form. The ensemble offers an unusual instrumentation, comprising Maeve Gilchrist on harp, Lee on cello, Eivind Opsvik on bass, and Jacob Sacks on piano, and it proves to be quite compelling. They create music that is at once jazzy, experimental, and ambient, finding a narrative in the tranquility born out of a mashup of style. The album unfolds slowly; its first two tracks prove to be lackluster, well-crafted but drab in their placidity. However, upon reaching “another old story,” Yeo-Neun picks up the pace. Here, harp and bass function in a plucky call and response with cello and piano; their delicately interlocking, rhythmic melodies become increasingly ornate as the piece continues.

The record shines strongest in the moments where ethereal sound is paired with extended techniques, perhaps most notably during “in stardust,” where the creaking of a bow being harshly dragged across strings eerily colors a sparse melody. “The longest morning” also creates a captivating blend of styles, mixing a catchy, folklike melody with scratching cello and chaotic improvisation. Each piece on Yeo-Neun provides a vignette of a different sonic territory, but it sounds its strongest when its paths are winding. Lee has triumphed experimentation, and the new routes she travels with Yeo-Neun prove most mesmerizing where a variety of styles meet in cacophony.

[8]

Sunik Kim: Triadic memories splintering and disintegrating, climbing knotted loops and the sound of breathing, Dean Blunt’s Redeemer refracted, harp clusters rising over low screeching glisses—this is a shocking turn for Okkyung Lee, whose work I’ve often had difficulty accessing due to my personal bias against much non-piano ‘solo free improv,’ which, especially on the noisier ‘extended technique’ end, often just sounds like a dead end, a race to punish an instrument for its own sake, an act of physical endurance and mastery that serves itself rather than the music. Yeo-Neun flips the script: the ascetic harp, piano and bass backing makes every croak and shriek of Lee’s cello a compelling textural element in a larger composition rather than just a solo show of technical prowess. More than anything, Yeo-Neun reminds me that notes are nice, and as much as ‘experimental’ artists and listeners ramble on about texture, timbre, and freedom from scales, a handful of perfectly selected piano notes will almost always take my breath away more than any showy ‘experimental’ fireworks display.

[8]

Gil Sansón: Listeners familiar with the work of Lee are likely to be surprised with the music presented here, as it sounds rather unlike her previous output to focus on the more gentle side of chamber music. It’s a peculiar type of ensemble, with harp and piano balancing cello and double bass, and the arrangements are carefully done and the music breathes comfortably in a diatonic environment that requires a bit of an architectural approach to avoid new-age territory. This is never a problem here and the seemingly meager musical material (from the point of view of harmony, primarily) is cleverly and sensitively handled by an ensemble working as a unit. The music never feels like a vehicle for Lee’s trademark cello sound, quite the contrary, she blends with the ensemble in purpose and intention, while at the same time retaining the visceral quality of her last production after adjusting it for ensemble playing. Somehow this often rough and expressionist approach, once adjusted to fit the present music, is not only still felt upon listening but it also prevents it from falling into the pitfalls of new age or ambient music. Despite what may appear on superficial listening, there’s plenty of interest here, from a purely musical point of view. And cello players who want to avoid sentimentality and the cliches associated with the instrument should do themselves a favor and check this release.

[8]

Mark Cutler: Well, this is surprising. I must admit, I’ve struggled with much of Lee’s solo output. I remember her once complaining around the release of Ghil that her gender and chosen instrument led to her being frequently booked with jazz and even classical acts. Against this, she insisted that she was not a cellist but a noise musician, and would like to be treated accordingly. Yet, when it came to the music, I too could not ignore that instrument. As she walloped and abused her cello every which way, I found it difficult to relinquish myself to the pure sound as I usually can with noise records. Something about the sound of those tortured sinews cut through the music for me. All I heard was a mass of stretching and scraping, and I didn’t enjoy it.

Some of that same stretching and scraping appears on Yeo-Neun, but it is, for me, otherwise an unrecognizable offering from Lee. Though she has experimented with a number of instruments and compositional styles in the last few years, never has she produced something so restrained and conventionally lovely. Playing here as part of a chamber quartet, Lee uses her instrument sparingly. Generally, Jacob Sacks’s piano and Maeve Gilchrist’s harp take center stage, playing Lee’s breezy compositions in near-tandem as Lee and bassist Eivind Opsvik skitter around the margins. These pieces supposedly feature both composed and improvised elements, and it speaks to the cohesion and restraint between the players that I cannot easily tell what is written and what is not. Yeo-Neun proves that, despite her prior assertions, Lee is equally at home in the conservatory as she is at Issue Project Room. I hope she continues to explore the capacities of the quartet format in addition to her more bracing solo output.

[8]

Leah B. Levinson: Here, simple motifs, limited harmony, heavy repetition, and spacious instrumentation make for compositions that breathe and invite wandering ears. This use of simplification and repetition is shared with popular film scoring styles, which takes me somewhat out of listening and evokes the album as a soundtrack, a work with its protagonist missing. This is especially jolting because Lee, primarily known as an improviser, leaves the space that would usually be filled by a soloist, unoccupied. Solos here are intermittent, sparse, and undramatic. At times, the use of repetition and counterpoint provoke hypnotic listening but moments of development often feel too insistent to continue an entrancing effect. I find myself wanting these arrangements to alternately do more or less, landing most satisfactorily only at the start of each piece when a new motif is introduced.

Revisiting the artist’s Tzadik debut, 2005’s Nihm (a similarly composition-heavy album), I found an analogue to Yeo-Neun with the former’s closing track, “4:37 Tuesday Morning.” It’s a standout of the debut for the way it teases cohesion and legibility while refusing both. On it, harp maintains on a two-note ostinato, which a cello/clarinet duo float around, producing long-tone dyads that counter settled harmony with blunt dissonance. Its elements are two separate agents in counterpoint, equal and complementary even when at odds; there is no missing lead. This and the piece’s refusal of development produce a nice sense of linearity and stillness, qualities I found myself wishing were further explored on Yeo-Neun, an album which, for all its strengths, consistently dodged my ear.

[6]

Jeff Brown: When all four performers play in unison it sounds like a giant instrument instead of separate parts, and from there they drift into melodies that hold conversations. You can hear this in how the wild stabs of improvisation (bow scratching, atonal note plucking) don’t distract from the rest of the instrumentation. When listening to this album, I envision images of happy solitude, and I get this sense of being content with moving on. The pieces unfold at a leisurely pace, and while things swell up occasionally, nothing’s out of place: these songs progress naturally. Towards the end of Yeo-Neun, a touching bit of sadness appears on “Facing your shadows”: The cello howls next to the harp, with the piano and bass erratically punctuating certain moments. Far from maudlin, this counterpoint suggests a sobering look at one’s failings, with quick, precise playing that builds before the final note rings out into poignant silence. Without words, the musicians create an atmosphere that’s as rewarding as a night to oneself.

[9]

Shy Thompson: The cover image of Yeo-Neun evokes something very similar to what I feel from the music therein: a window into something emanating a soft and gentle glow. It feels approachable, yet the tiniest bit obfuscated. It’s a comfortable warmth that invites you to bask alongside it, getting to know it by letting it wash over you. Having been familiar with much of Okkyung Lee’s work, what surprises me most isn’t the change in style, nor is it the unexpectedness of hearing her perform in a chamber ensemble; it’s the feather-light touch and incredible restraint. What I’m used to hearing from offerings like Noisy Love Songs or Ghil is an unrestrained fervor that lays bare a devotion to her instrument. Yeo-Neun shows me that intensity in a different—but equally important—way. Her cello speaks to me just as sternly as it always has, but more softly. Rather than imply this is more personal or emotional than what she has done prior, this reminds us of the breadth of her emotional range. We’ve had a lot of impassioned musical conversations, but this one feels like a serious heart-to-heart.

[7]

Joshua Minsoo Kim: I leave my window blinds open nowadays. Not that I ever left them closed indefinitely, but I’ve made a conscious decision to let in as much light as I can—it’s just that much easier to wake up when the sun’s rays keep me accountable. Yeo-Neun is an album that feels like those 9 o’clock blues, when getting up feels undesirable given the day ahead. I sense a serenity to these tracks, even in the most strident of passages. Maybe it’s just that these tracks find their DNA in Korean ballads, but I sense an identifiably Korean wistfulness here, the kind that veers on the saccharine but grips it so tightly because it’s a form of mourning, a means for survival. I let every bit wash over me: the stately piano, the cascading harp, the spurts of frenetic cello and bass. They remind me I’m alive, and push me ever-gently towards my next step, even if it’s just brushing my teeth at a reasonable hour. The title, which translates to “opening,” is poetic: Yeo-Neun reminds you to exist, that there’s more that awaits, to embrace the pretty and ugly moments all the same.

[8]

Alex Mayle: Lately I've been listening to a lot of ceòl mór. Originally played on the clàrsach, it hails from the Scottish Highlands and is built around improvisations of a simple melodic theme called the ùrlar. The clàrsach, also known as the Gaelic harp, is heavily featured on Yeo-Neun and is played by Maeve Gilchrist, though in a very different style and context: ceòl mór is played in a flowing legato manner dissimilar to the distinctly rhythmic and occasionally staccato sound found here. That difference highlights one of the many ways this album caught me off guard, which was a recurring motif throughout my first handful of listens.

My main point of reference for Okkyung Lee is Ghil, a solo work filled with dissonant cello explorations, so I was startled at the pleasant harp playing at the beginning of the record. This is the debut of her new quartet and it is immediately clear that while Lee is the bandleader, she's neither trying to steal the show nor repeating what she's done in the past. Drawing from pop and Korean folk, each piece is built from simple melodic phrases, repeated and improvised in gorgeous fashion. The Yeo-Neun Quartet is not afraid to get ugly, though, and one of the finest glimpses of that is halfway through "in stardust (for kang kyung-ok)" when Lee and Opsik use their bows to make an discordant creaking while Gilchrist and Sacks form a somber melody that's hauntingly beautiful.

Similarly on "facing your shadows," Lee and Gilchrist take turns creating beautiful dissonance while Sacks and Opsik play an otherwise tonal melody until it all comes crashing down in a lovely mess of sound. There's more chaos still, such as on "another old story (옛날이야기)," though it is few and far between; the bulk of the album sees the four bouncing simple melodic phrases between each other, adding embellishments as the song progresses. The complexity that arises from these relatively straightforward ideas reminds me of improvisations on the ùrlar in ceòl mór, and every moment uncovers more depth to be explored on a future listen. When I first started listening to Yeo-Neun I was surprised by what seemed to be an album filled with simply pleasant music, relying heavily on the intrinsic beauty of well played instruments, but each successive revisit revealed explorations in timbre woven into intricate melodic phrases.

[9]

Average: [7.55]

Still from Queen of Diamonds (Nina Menkes, 1991)

Thank you for reading the thirteenth issue of Tone Glow. We hope you’re holding together well.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.