Tone Glow 166: Writers Panel & Recommendations Corner, 10/30/2024

Our Writers Panel on Able Noise's 'High Tide' and Aeson Zervas' 'Hazlom'. Also: Our Recommendations Corner on Flagdoku and the Kasane Teto Plush Doll.

Writers Panel

For our Writers Panel, Tone Glow’s writers share thoughts on albums and assign them a score between 0 and 10. This section of the website is inspired by The Singles Jukebox.

Able Noise - High Tide (World of Echo, 2024)

Press Release info: Able Noise are a cross-continent duo based between The Hague (NL) and Athens (GR), built around the experimental baritone guitar and drum playing of George Knegtel and Alex Andropoulos. After a few formative attempts at collaboration, they officially came together in 2017 as the Able Noise we see now, uniting over shared thoughts on art and performance encountered while studying at The Royal Academy of Arts in The Hague.

The shift to a studio environment [for High Tide] was a significant one, since Able Noise was primarily conceived as a live band, thinking of and writing for the live concert experience specifically. Consider their practice an Active Performance of sorts, one that seeks to challenge understandings of the medium of the live arena, how its properties and limitations can be addressed creatively, and the dialogical relationship between performer and the audience. […] High Tide is a woozy and often disorientating listen that plays quick and easy with conventional notions of structure, at once both centreless and impressionistic, yet somehow guided by an imagined formless space.

Purchase info: The album is available to purchase at the World of Echo website and at Bandcamp.

Matthew Blackwell: Able Noise is a live band built for the studio, a duo that features five or six musicians. George Knegtel’s guitar and Alex Andropoulos’ drums form the foundation of the group, but both of these facts mean that the foundation is constantly shifting. The first 10 seconds of the first song of High Tide are all it takes to realize this, as “To Appease” takes its woozy, hallucinatory quality from tape being manipulated more than the performance itself (listen closely and the tape machine’s reels themselves are audible). The cast of collaborators further disturbs the band’s boundaries, with new instruments appearing and disappearing—suddenly a new voice, a clarinet, a violin joins, not as featured artists but as temporary members. It’s arty but welcoming, it’s dramatic and experimental, it’s post-rock on a smaller, but no less ambitious scale. Not to sound hyperbolic, but there’s some Gastr del Sol and some Dirty Three and some Still House Plants in Able Noise’s DNA. It makes for an unstable mixture and it’s all the better for it.

[7]

Michael McKinney: In an interview hosted by Glamcult, the members of Able Noise—Alex Andropoulos and George Knegtel—repeatedly return to the import of place: the idea of a venue informing a performance, or of how they tie their improvisations to whatever moods hang in the air before they play a single note. This is hardly a new idea, but it does set up an interesting question: what happens when you replace the stage with a studio? High Tide, which is presented as the duo’s debut LP, offers up ten different answers.

High Tide is a record of big swings made quietly. Its most (and least) successful moments are its uncanniest: it’s old-school math rock with half the tracks on mute; it’s lethargic ambient music; it’s pastoral folk held underneath a storm-filled sky. This is a record made entirely of trapdoors and false walls; notably, Able Noise invite a raft of collaborators but leave their contributions up for debate. The disorientation, it seems, is the point.

The album’s first thirty seconds feature no less than five tempo changes, but it’s an obviously digital thing; you can practically hear the hands fiddling on the mixing board. Location is still king, and here, they’ve got nothing but each other, their collaborators, and a recording studio. In taking advantage of everything that this entails, they recall the histories of dub and Screwtapes alike, blurring production and post-production, treating the decks and dials as an equal partner in their work.

It’s tempting to link High Tide to the members’ other media of choice. Both members have backgrounds in art; Andropoulos studied sculpture and Knegtel grabbed a camera. Both are acts of creation, but also of reduction and preservation, and they offer a helpful frame of reference here: what material gets to stay in the frame? What material should wind up on the floor? This is a record where you can hear the sides sloughing off mid-session; its tracks are often a bit shaggy, with the loose ends left pointedly hanging. (If it weren’t all so low-key, it would be confrontational.) Process work can be a captivating thing; there’s a million reasons sketchbooks end up in museums. Not everything on High Tide moves me as much as I wish it did, but its best moments tap into something elemental: how does your world inform your work?

[6]

Jinhyung Kim: Here’s a cold take for Tone Glow (and maybe for some of those reading): the only Still House Plants record I really like is their self-titled EP; its seamless grooves and tumble-dry drum work are threaded by vocals that just drip with melismatic longing. SHP's other releases don't do much for me. They’re nice enough, and Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach does something wonderfully bold with her voice on later records. But despite acquiring a more jagged edge, Fast Edit and If I don’t make it, I love u have failed to sink their teeth into my memory; the warmth that subtends the earlier music feels as if it's evaporated, without anything to replace it and make the dislocated elements of its sonic palette cohere.

When Able Noise’s Recordings came out in 2020, I couldn’t help but place it under SHP’s shadow—not just because it came out on GLARC, who also put out the SHP self-titled back in 2016, but also because Able Noise’s sound is evidently cut from the same cloth: guitar micro-loops with a very similar tone, irregular yet satisfyingly iterative drumming, etc., in service of a mellifluous (post-)post-rock-y zen. The most salient difference is how Able Noise likes to subtly layer and process material—e.g. loosely doubling (or doubling + staggering) a guitar part to make the left and right channels flutter in and out of unison, or saturating the aural field with ambient fuzz or light distortion; furthermore, the recording quality itself varies, putting the listener at different distances from the music. One is beguiled by the unity of a patchwork tapestry, seams and all. Pleasant, definitely. But also not really my thing—too few hooks or divots in the surface of the thing for me to latch onto. I forgot about Recordings almost as soon as I stopped listening to it. Comparing again with SHP: whether you sand down or serrate the edges of this particular sound, perhaps doing so threatens to dissolve the delicate contours that hold it together.

High Tide, unlike Recordings, does not obfuscate the demarcation of individual tracks with a flatly nominal “side A” and “side B,” but the songs ebb and flow in a broader continuity. It’s a process of refinement more than anything else—some cuts even seem to be new versions of passages heard on Recordings. The mix sounds more consistently full and detailed without sacrificing the warm patina of room noise or tape hiss, allowing for the band’s little studio tricks (especially cross-channel ones) to shimmer with greater clarity. My favorite moments are when Able Noise play with modulation; “To Appease” is a standout for relying primarily on speed-shifting tape playback of a simple guitar-and-drum groove to provide accompaniment for muted sing-song transmissions from the pleroma. In the closing minutes of “Providence,” a rapidly ascending guitar motif produces an analogous effect—a barbershop pole amidst a percussive flurry. Ultimately, though, there’s little about High Tide that makes it any more memorable than the last record. I enjoy hearing these sounds as they wash over my room, but no more than I like my big, old wooden desk—it’s good, sturdy, reliable. But I’m not taking it to my next apartment.

[5]

H.D. Angel: Your friend-of-a-friend’s go-to, one-pan recipe. The two main ingredients (meditative Raincoats-ish kitchen sink post-rock, nerdy electroacoustic noodling) each hang around the right level of accessibility: not so out-there that they ask for rarefied virtuosity, not so obvious that they require a savant to be anything but boring. Idly watching the cooking happen is worth whatever results from the half-hour spent. Maybe, with a little elbow grease, you could “do it yourself”—but they did it for you already, so just chill.

[6]

Marshall Gu: Able Noise once told Glamcult, “‘Experimental’ serves as somewhat of a disclaimer to unsuspecting audiences of the fact we refrain from employing rock structures and that the drums often don’t play a straightforward beat. Just a ‘heads up’ almost.” I wish I got the notice sooner! This is not experimental beyond that. Drums not playing a rock beat and the shrugging off of conventional structures in rock music have been done to death since rock music took off, and so the “experiments” on High Tide sounds like people playing around with their instruments rather than true experimentation—or maybe the line between experimentation and play is too blurry to tell now. To wit, I’ve heard all of this before but shaped into more pleasurable songs by others. Is “Ceaseless Sun” not just them working out a melody already written by the Incredible String Band? Is “To Two” not just them working out an American Football practice session from 1998? Is “Garden” not just any cute twee singer/songwriter thing, is “Inertia” not a bassline aimlessly moving around so someone else can play what sounds like flute over top, and is the first 90 seconds of “To Appease” not just someone playing around with a knob? “How does one create a definitive recorded music initially rooted in improvisation,” the press release wonders. If only a century of jazz worked that out for us!

[2]

Joshua Minsoo Kim: A lot of tracks on High Tide are funny. Or at least they start that way until the humor leads to unsuspecting awe. You hear that on “To Appease,” a track whose title feels like a nod to those wanting the music to land at a normal tempo after all the tape manipulation. “Providence” sounds like a drummer duetting with the patter of rain, or maybe that’s the sound of windshield wipers. It sort of just exists before erupting into a blissful wall of sound—filling all the silence, you realize, is enough to bring serenity. It’s the simplicity of these maneuvers that keep winning me over. “Inertia” sounded crazy over my car speakers because its simple bassline is massive and bloated compared to the sparkling ambience. “To Two” is slowcore turned mediumcore turned fastcore and then slow again; by the time it settles, it sounds like the tape’s been garbled. This is an album about the joy in simple experimentation, and noticing the huge repercussions of every musical decision (a number of these tracks walk a thin line between the dingier New Weird Americana acts and the prettier Freak Folk ones). It’s an album where the “studio is an instrument,” except at the smallest possible scale.

[7]

Mark Cutler: A self-described live-only band, Able Noise use the occasion of playing in a studio to make playback an explicit part of their sound. On opener “To Appease,” the recording of Knegtel’s guitar playing lurches up and down in pitch in a way that suggests someone fiddling with the speed knob on a record player. Eventually the audio careens so low that it becomes a tuneless, bassy rumble. To my surprise, it stays there while what seems like an entirely new song begins in the detritus of the old. Other tracks clearly loop, layer or reverse parts of the instrumentation in ways that would be near-impossible in a live scenario.

Nearly half the tracks here are under three minutes long, with the shortest being just 93 seconds. Though I enjoy each individual track on the album, their brevity and abruptness makes this feel very much like a collection of clippings from longer, looser improvisations. Given that the absolute best pieces are the 5+ minute ones, I wish Able Noise had trusted themselves and their audience enough to situate more of these fragments within the longer stretches of improvisation that generated them. A more expansive—even if less focused—album might better wed their live and recorded output.

[7]

Matthew LaBarbera: Oh, it’s nigh time for some labile joys–free to prise a prize from apprise–to undo Hegel’s ploys. It’s just you and me out here drawing lines in the sand and chasing away the sea. Buttered snare rolls for breakfast, and later we’ll fight for dinner. It’s dizzying just being outside, seaside, dayside, foreside, topside, underside, downside, by-your-side. Besides, high crimes and misty meaners, just what could they mean, all cloudtalk and fogface? Grid extends into volume and, I’ve gotta be honest with you, I’m lost.

Every day I take my tiny dog walking across our luckless little isle. He’s really a small thing, and ours is a wind-cursed part of the world, truly wuthering stuff. Rocky hills like heads offer no lee, wirehairs flattened and combed by the tremulous sacrament of the Anemoi. Scrabbly strands of footing just cliffside, and all I can imagine is him at a hop and suddenly getting whipped up, drawn up like a kite, Rufus Velificans. His bodkin bark dissipates into nothing, and I’m left standing there in a cauldron of winds.

I’m not sure about all this tapping the glass. Who’s making the demands here? Appease of cheese for lunch (with bread and olives), and wine for washing. I shall ‘fetch thee jewels from the deep, and sing while thou on pressed flowers dost sleep.’ A bedding of blossoms, a chorus of nightjars, and cricket guitar: hortus cubiculatus. Drunk on your own inertia, satisfied as the center of the spool until the whole thing gets wobbly. Coming a cropper fernlengths, reeds whistling aulos-song in Sakadian rhythm, argot of an Argot, and splashing out on the copper shore of formlessness.

I got this scar back when I was a kid. I once wandered way out into the marshes, past the Stewarts’ property to where the air turned briny and effluvial. Each step was a war against vacuum, and I was hitting a faulty rhythm—shluup!, balance, puhluh!—too fast. In my haste, my march faltered, and I, turning on a mucky pivot, was out of coordination. Grasping hand meets slicing edge. Mr. Stewart called it speargrass, as he wrapped a bandage round purlicue-wise, but I’ve never been able to find the proper name. Wide as a palm and terrifically sharp, the long leaves had an almost iron glint in the sun.

All right, I’ll start making some demands now. Firstly, we jettison genre; a style is an instrument with which to render script. Instead, we bait our traps with tantalizing concepts, a counterspoor. Discard if we can the paradigm of ‘idiomatic tools towards non-idiomatic ends’ and let us frighten off its grammar. The guitar-bass-drum-voice machine is not a series of blanks to be filled but a fundamental unit, a ground beneath which all things take on strange and uncertain relations. It’s really about what’s possible to imagine once the inviolable has befallen scientific reduction. This is what happens when you disassemble the motor. The monolith loses all hieratic gravity and is simply returned to element. And here is the transformation, the brand of distinction, the passage from nonage: to recognize the fragments of the altar as more than just inert pieces of rock.

I’ve always felt like I could see in slow motion like the action of the world was unfurling before me. Not even traveling in lines, along trajectories, but spilling out as turbulences and microturbulences and macroturbulences all swirling around each other, pulling taut pockets of countervailance. Like I’m at a holographic remove, mist curling around my slow swiping fingers, ebbing and eddying.

[gribouillage]

These things take time, and we’ve got plenty out in the intertidal. That’s why I need you and you me. The fable toys with coherence but that’s facade. We’ve taken the thing apart and need to put something back together, whether it comes out a vacuum cleaner or a machine gun. Yes, we proceed by way of dynamic duolectics rather than static hermitneutics. Would you prefer to be Dipoenus or Scyllis? Scylla or Charybdis? When the process gets stuck, just give it a solid thwack and watch it clatter on somewhere new, finessing the sly divide. It’s monstrous, in a way; a mutilation, maybe.

[7]

Average: [5.88]

Aeson Zervas - Hazlom (Heat Crimes, 2024)

Press Release info: Past meets present on nine swaggering renditions of the fiery Cairene street rave sound shotted by likes of EEK & Islam Chipsy that has emerged in ballistic permutations from the likes of ZULI, 3Phaz and 1127 in recent years. No doubt it’s bang up for it in a way that his preceding album did not hint at, and all the better for it, connecting threads between the deep past and heritage of Mediterranean rim musics that continue to inform and branch into the present. Plangent horns and microtonal keyboards edge into weirder basslines gnawed by noise. Zervas’ zeroes in on the relationship between Greece and Egypt and the broader Arabic world here, but with a crucial artistic license that prompts him to mess with the aesthetic and find something fresh but timeless in the process, uncannily echoing in parts Actress’ hazed out take on Detroit techno.

Purchase info: The album can be purchased at Bandcamp.

Michael McKinney: For all the immediacy afforded by a well-tuned bassbin, dance music is awfully tough to pin down: it exists between spaces, times, and histories, jumbling up universes even when it’s aimed directly at a dancefloor. It is an international endeavor where the most meaningful interactions often take place next to sweat-soaked strangers. It is a tangling of universes presented as something deeply physical, even if many of its listeners never set foot on a dancefloor, preferring to trawl Discogs or YouTube, chasing threads across decades and continents in the process.

Hazlom sits at each of those intersections. It hints at full-on rave ballista but never quite pulls the trigger; it suggests vertiginous ambience but is content to peek over the edge. It is a series of scuzzy and blown-out mahraganat-techno tracks, its sound pulling from Athens and Detroit in equal measure. Each beat sounds like a rave half-remembered, and each melody recalls generations of Mediterranean folk-music traditions; it is built upon dial-up synthesizers, and drums filled with ball bearings, and speakers hammered within an inch of their life.

In its best moments, Hazlom recalls, of all things, Ghettoville, Actress’ masterwork of abyssal electro-dirges: a dark cloud hanging over a warehouse rave, with beats suffocated underneath the weight of all this pitch-black ambience. It also brings to mind Slikback, a dizzyingly productive electronic-music producer whose work vaults scrambles the borders between trap, noise, and guns-blazing techno. Like the best stuff from both of those names, Hazlom goes deep on a highly specific bit; unlike them, it’s just not that compelling once the rubber meets the road.

Maybe it’s unfair, but the most compelling thing about Hazlom is its ideas. It’s got all sorts of proper nouns that ought to hit: zero-gravity hard-drum? Ambient mahraganat? Street-rave illbient? Sure! But by the time it’s run its course, it feels like a series of tools you’d hear in a particularly adventurous DJ’s set—the first hour of an all-nighter from ojoo or Objekt or ZULI, say. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, and this is doing something compelling in that space, but as a full-length, it just doesn’t offer all that much to latch onto besides the grim—if compelling—ambience of it all. With Hazlom, Aeson Zervas is trying to do something extraordinarily difficult: a full-length LP of dance-not-dance music, stuff that carves out a ravine between peak-time raves and the 5 a.m. drive home. It’s commendable, to be sure, but that’s an awfully high bar to meet.

[5]

Maxie Younger: Hazlom opens with its three strongest songs: great, cutting loops that draw brittle spirals of noise, whorling ever-closer to a nonexistent center. Aeson Zervas’ approach here—a more kinetic, yawping upgrade to the sleepy yarns of his self-titled release from May of this year—is terrific in longer bursts when he allows time for a track’s every element to move at its own pace, rubbing and clashing against its neighbors as though their synchronicity forms by mere chance. This phenomenon comes to a head on “Χωρίς τίτλο 10,” the peak of the collection, where mottled, greasy synth lines ooze menacingly between shrill walls of drum-machine staccato that jolts forwards and backwards with mercurial glee. The album’s best tracks all ride on that rare lightning-in-a-bottle quality, like you’ve stumbled onto a warty, shelved experiment; it’s no surprise, then, that the magic doesn’t strike nearly as often as one might like it to, particularly on the back half.

There’s a great EP tucked inside Hazlom, but its gradual slide into less dynamic, filler-y tracks and weaker grooves give it the feel of a deluxe reissue, the chaff from an overflowing folder of demos and b-sides interleaved with top-level cuts. This effect isn’t enough to eclipse the highest highs, but it does suggest an opportunity to hone in. Zervas’ wildest instincts are moving his nascent body of work in a good direction; all that’s left is for him to follow them all the way through.

[6]

Samuel McLemore: Hazlom is a perfectly fine album in a vaguely techno, ambiguously ethnic style that doesn’t do enough to stand out. I could quibble with multiple aspects of the musical compositions that aren’t to my particular liking—the rhythms don’t have enough movement or drama on most tracks, the textures and timbres are terribly monochrome through 95% of the album, there’s no arc or coherence to the track order—but I think the main fault is the lack of a definable personality or point of view. The requisite Boomkat blurb makes a comparison to Actress, which is smart because Actress is not only an obvious influence, but also represents a best-case scenario for the style Zervas is working towards. But the comparison also backfires because part of the appeal of the British producer’s rather uneven discography is the personality that bubbles up through the otherwise anonymous music—unique compositional methods, mixing choices, samples, melodies, and a million other idiosyncratic details form to make the picture of this man. Whoever Aeson Zervas is, he’s not there yet.

[4]

Mark Cutler: I had to check multiple times that this wasn’t a beat tape. Ever since Fatima al Qadiri’s Global .WAV project ten years ago, I’ve expected the aggressively minor-key dance music of the Mediterranean region to stage a full-scale takeover. But these tracks, as they stand, don’t have enough direction to sustain their runtimes. Notable exceptions include “Χωρίς τίτλο 9” and “Χωρίς τίτλο 16,” which layer on enough competing elements to fill the sonic space on their own. But for the most part, I really need a Greek guy rapping over these instrumentals ASAP.

[6]

Jinhyung Kim: Earlier this year, I was obsessed with Cheba Wahida's Jrouli—a contemporary raï record whose sheer motor propulsion and declamatory force hits like a fucking freight truck. I like to make a distinction between passive and active hypnosis as musically induced states: passive hypnosis is when I tune out the music, letting it permeate the space while occasionally tickling my perceptual periphery; active hypnosis is when whatever’s playing holds the center of my attention, always pulling it to the sound source. In either case, I like to do other things, but the former lets me focus while the latter helps when I'm doing something from which I want steady distraction. Of course, both also allow for dedicated listening—I can listen for minute variations and subtle shifts, or I can open my mind to a swirling onslaught.

Hazlom reminds me of Jrouli not for any strong formal similarity—even as a shared North African folk tradition comes into play—but because I find both actively (and powerfully) hypnotic. Both capture a sound whose riotous energy conjures a lively sociality; besides a plethora of vocal samples that break through the fold in one beat or another, each independent gesture or layer in the mix bears a human signature, despite its synthetic genesis. Aeson Zervas repeatedly impresses in his ability to produce an irresistible forward drive out of what at first appears as a haphazard disparity—until the listener adapts to the idiosyncratic soundscape and pulse of any given track; it’s this injunction to adapt that constitutes Hazlom's active-hypnotic pull. The varying timbral shapes of all the individual sonic elements maintain their rough edges when jutting up against each other, generating delicious frictions rather than blurring together. I don’t know if I’d describe any one of these songs as an “earworm,” but there are plenty of peculiar motifs or melodies that lodged themselves in my musical memory, echoing with the same persistence as a line of conversation whose isolation from context amplifies its profundity, or humor—or both.

[7]

Joshua Minsoo Kim: It’s been nearly a decade since EEK’s Kahraba, an album that introduced a large number of Western music nerds to mahraganat. Inspired by hip-hop, reggaeton, and grime, mahraganat brought shaabi—an Egyptian folk music—into the 21st century’s increasingly globalized musical network. But as with any sort of “genre introduction” to “music nerds,” Kahraba wasn’t exactly a representative album, as it wasn’t aiming for the sort of pop music that could rack up millions of views on YouTube. Instead, Kahraba zoomed in on the genre’s mesmerizing beats to create a sort of relentless psychedelia, where nonstop percussion and squiggling synths could be a multi-channel conduit for ecstatic release.

Aeson Zervas’ music is distinct from either of these things, as well as the works of underground Egyptian producers like 1127, for constantly interrogating songs as time capsules. His self-titled LP would put old tracks through gauzy filters, amplify traits associated with low fidelity, and maybe throw in a synth that already felt like a nod to a bygone era. Hazlom is a much more interesting and elaborate consideration of the past. The opener features a sample, but to hear him incorporating a beat that carries the same spirit of the original track feels like a whip pan from past to present—something even more pronounced with the split-second trap beat that closes the song.

It’s all about these slippages. An incantatory vocal sample anchors “Χωρίς τίτλο 11,” but the presence of spoken word, as well as a gaudy synth pad, makes the song feel—if only for brief moments—like a corporate jingle by way of James Ferraro. Much like Kahraba, the appeal is in the compounding of the digital and the “real.” Where that album’s imperfect drumming would occasionally remind you of the person playing—as if he’s trying to catch up with (and bolster) the synths—so too do these samples oscillate between having a pure rhythmic and textural function, and then grounding everything in an actual place and time. “Χωρίς τίτλο 12” sounds like you’re hearing people at a street market, but then the repeating, sampled yell will remind you of its artificiality and the use of modern technology.

If you actually go back and hear old shaabi—electro or not—what’s alarming is how so much of the stuff sounds just like Hazlom. Listen to Ahmed Adaweya’s “Ady El Marakeb”: the recording is shoddy, the singers sound like they could be samples themselves, and the whole thing erupts into a sort of cacophonous noise—due in no small part to the garbled mix. What Zervas does here that he didn’t on his self-titled record is complicate the way we think about traditional music, especially the kind that’d be played in everyday scenarios and on the street. In purposefully recapturing the accidental aesthetics of older songs, Zervas clarifies that all music is mediated by a million factors, be it recording technologies or the circumstances that bring people to hear it in the first place. Nothing can ever capture a feeling or genre or era perfectly—even the current one. And yet, by making an album that sounds like it could’ve been made in at least four different decades, he gets pretty close.

[7]

H.D. Angel: What’s in a space? Lately I’ve been pondering the environments we attach to music in our minds, like the filmic, dimly-lit rooms of Portishead or the sunny vistas and neighborhoods of ’70s Laurel Canyon rock. Per “dancing about architecture,” plenty of effort has been expended over the years, by both musician and listener, trying to map abstract songs to the concrete spaces they conjure and vice versa. Imagining a vivid scene that gives shape to a recording is such a hard-wired emotional response that we rarely question it unless it inspires some kind of nagging cognitive dissonance—which can be exploited for fun. Plenty of electroacoustic music complicates our imagined spaces. Along more functional lines, you might get what someone like Actress does to dance music. It’s removed from “the club,” but not in the traditional IDM way, with its own self-contained playground of techno-utopian sound design. Instead, he’ll give you a sketch, a few gestures, and force you to play charades. What’s a 4/4 house track when the kick drum has been sucked out through an airlock, or actually kicked around on the city pavement? Soon, our own architectural instincts as listeners start to feel a bit cryptic.

These tricks of space are always cultural, too. Recorded audio will fill whatever space you allot it—AirPods, a studio, a phone speaker in a glass—but that might not be the space it’s mixed for; thus, the memes about listening to party music like this. Music can conjure spaces from thin air, but it also anticipates the ones it’s played in. A rap song built for America’s ubiquitous car stereo might be pre-treated to sound like the inside of a vehicle, with windows rolled down for a smooth night drive on the interstate; or like the outside, as it’s cruising and rattling down a summer street.

I’m not fluent in electro-chaabi, the Egyptian dance genre that Aeson Zervas mines on Hazlom, but from its blistering, tinny, EDM-wise timbres I readily imagine the lively outdoor gatherings it’s meant to accompany in Egypt. Zervas’ tracks are extended, Actress-style impressions, focused on the odd qualities these spaces accrue in our minds and memories. The hazy, microtonal loops that center these songs serve split purposes, as both the driving lead melodies of the tracks themselves and the nostalgic sampled material that roots them in a richer history. Walking around with Hazlom’s tracks in my ears, I’m confronted with a panoply of aural spaces, all butting heads in my own head: a sampled singer or instrumentalist working as a shaabi street performer in some bustling corner of Cairo in the recent-to-distant past; the Aeson Zervas track itself, blaring from a speaker in the same place in the present; Zervas at his laptop, clicking around intently; a noisy, claustrophobic textural layer within my headphones, which draws me into my contemplation; and the world around me, perhaps a section of forested creek by a North Carolina sidewalk.

The best tracks deepen this experience with further abstraction, like the feminine-voiced ASMR snippet enjambed into “Χωρίς τίτλο 13.” There’s a certain joy in this kind of naive confrontation with an unfamiliar sonic space. Surely many of the American teens exposed to Brazilian funk through RateYourMusic will complain that the mixing sounds muddy and monotonous in their $20 SkullCandys, but some will reach out towards the work, watch some videos of bailes, imagine being physically shaken by those massive speaker setups, and annoy their parents buying equipment to try and replicate the fun at home. And for all the navel-gazing we might do about our different experiences with art being incommensurable, when a song gets really weird or distinctive, I think everyone’s brain can go to a similar place.

[7]

Average: [6.00]

Recommendations Corner

For our Recommendations Corner, Tone Glow’s writers have the chance to write about anything they want that’s caught their interest.

Flagdoku

I wish I had a way of rationally explaining my newfound interest in flags. The best I can do is to say that, one day in July, I woke up obsessing over how I would perform in a hypothetical scenario where a man-on-the-street interviewer pulled me off the sidewalk and asked me to name a bunch of different country and state flags. The idea of bombing the quiz and coming off like one of those terrified rubes you’d see profiled in a “JayWalking” segment irritated me so much that I decided there could be no alternative but to spend the remainder of the month committing each and every relevant flag I could find—EU members, OPEC countries, unrecognized governments, regional independence movements—to memory. Nights passed in delirium as I drilled Seterra quizzes with the clinical efficiency of a high school quiz bowl champion: 100% scores were deemed false positives until I could repeat them back to back, three times, four times in a row. I came out the other side with enough knowledge to run a Jeopardy category several times over and have strong opinions on successful flag design (“Good” Flag, “Bad” Flag can stuff it.)

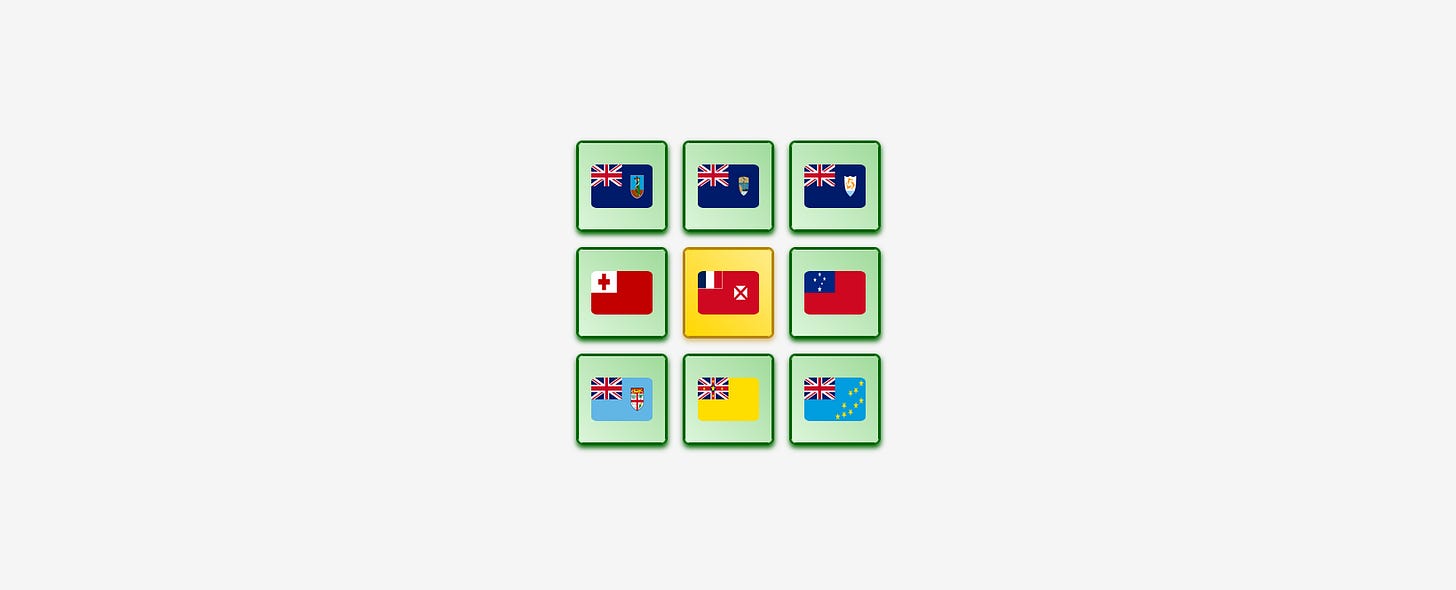

It’s tough to say what the point of all this is, what it means for my life, and why it doesn’t qualify as an immense waste of time and mental resources. Perhaps, psychologically, it gives me a means of seizing some form of intellectual control in a time when my relationship with the world is usually defined by an overwhelming lack of knowledge and context (if you could bottle the feeling of calling out the correct quiz show answer moments before it’s revealed, it would surely sell out in minutes); but, I’d rather not chase a pat justification and instead embrace that this is going to be My Thing for at least a few more months. My most cherished pastime during this period of feverish acquisition has been the browser-based game Flagdoku, a new high point of the wave of “daily -dles”—novel, minimalist trivia puzzles with easily shareable results screens—that infested the internet after the Wordle explosion of 2021. The game is quick to grasp: fill out a nine-by-nine grid with different flags that match the intersecting categories of each column and row. To make things a little more interesting, each puzzle features a “flag of the day” that fits every category at once. For instance, the flag of Iceland meets all of puzzle #161’s stipulations of Nordic Cross, White, Red, 3 Colors, Bands Only, and Main Color: Blue.

Flagdoku is a capricious, exacting, yet strangely lenient taskmaster. Per the game’s labyrinthine database of potential answers, flags like the controversial Minnesota redesign and Snake Hill, an Australian micronation, are considered to have only two total colors, blue and white, despite featuring multiple shades of the former. On the other side of the coin, the flag of the Northern Mariana Islands picks up a “Black” designation from the thinnest stroke outline surrounding its central star and a small shadow at the base of its posterized latte stone graphic. Part of the fun of following the game’s daily challenges is seeing the increasingly granular requirements for solutions—“Name: 4 Letters,” “No-Touch: White, Yellow,” “Star color: White”—as the glut of options make simpler categories less rewarding to puzzle out. There aren’t many activities that tap into the obscurantist music-nerd thrill of churning out gigabytes of Topsters charts crammed with rows of evocative, possibly apocryphal album covers (does the “Laser Kiwi” flag really need a database slot?), but Flagdoku’s completionist, heads-only attitude—buoyed by a progress meter that shows how many of its 1,000+ flags you’ve used as successful responses—makes it the perfect venue for flexing with ridiculous deep cuts. As far as addictions go, it’s in the upper echelon for at least locking some actionable knowledge in my brain; whenever I drop the habit, at least I’ll know I can tell apart a Saint Helena from an Anguilla. —Maxie Younger

Kasane Teto Plush Doll (Round1, 2023)

I probably don’t need to explain who Hatsune Miku is. Even if you’re relatively disconnected from Japanese trends, even if you don’t know what the Vocaloid voice synthesis software is, and even if you’ve never heard a single song that uses her sound bank, you’ve probably at least seen her depicted somewhere. She’s become a bit of a folk hero, a connective tissue that bridges the divides between nerdy Japanese subcultures. She sits at the confluence of anime, music, visual art, and video games, almost as an avatar for fandom itself. If you know her, you almost certainly adore her.

I definitely need to explain who Kasane Teto is. She was conceptualized as an April Fools joke, a barely-believable prank in 2008 that may have convinced a few thousand people at most she was going to be the next official Vocaloid character. Her design bears a strong resemblance to Miku; her color scheme is deep red instead of the iconic mint green, and Miku’s long twintails are swapped out for two tightly coiled ringlets. The “01” tattoo adorning Miku’s arm—which represents her status as the first character created by Vocaloid’s parent company Crypton Future Media—is replaced with “0401,” giving the game away that she was born on April 1st. Despite her obvious intention as a throwaway gag, she started to develop a fanbase. Vocals were provided by singer Mayo Oyamano and Teto was made into a sound bank for UTAU, a competing voice synthesis software under a shareware license. (In some of Teto’s most popular early songs, UTAU creators make a point to mention that Teto is for the proletariat while Miku is the capitalist option.) Still, it’s not like she was ever particularly popular.

Fast forward to 2023: Vocaloid is no longer the undisputed best voice synthesis program. The word has become more of a general descriptor for music with robotic vocals than something that’s only made by the software that bears the name. Synthesizer V, which has become a popular option for Vocaloid producers, announced that Kasane Teto would be legitimized as an official sound bank. To commemorate the occasion, she was given her own design that wasn’t just a riff on Miku. With this, the dam was broken and she exploded in popularity. Art of Teto, in both her old and new designs, flooded Japanese art communities. For the first time ever, the most popular Vocaloid songs were using the voice of Teto (both instead of and in addition to Miku).

As I hold a plush Teto doll in my hands, which was released in collaboration with the Round1 arcade chain, I’m in disbelief that this object even exists. I remember how huge a deal it was when she was added as a DLC character in the Miku-themed Project Diva 2nd rhythm game as a cosmetic skin, her likeness acknowledged in an official capacity even though she was still singing with Miku’s voice. Now, Teto feels more real than ever—and it’s all because a persistent sub-fandom willed her into existence. —Shy Clara Thompson

Further Ephemera

Our writers do more than just write for Tone Glow! Occasionally, we’ll highlight other things we’ve done that we’d love for you to check out.

Vanessa Ague wrote a review of Max Richter’s In a Landscape for Pitchfork. She also wrote about Charles Gayle, Milford Graves and William Parker’s WEBO for the Quietus. For her website The Road to Sound, she wrote about Basilica Hudson’s 24-Hour Drone event. Ague also wrote about the Sun Ra / El Saturn archive for I Care If You Listen.

H.D. Angel wrote a review of Nídia & Valentina’s Estradas for Pitchfork.

Matthew Blackwell wrote a review of Anna Butterss’ Mighty Vertebrate for Pitchfork. He also wrote about BASIC’s This is BASIC for Pitchfork.

Rae-Aila Crumble wrote a review on Yeat’s Lyfestyle for Pitchfork. She also wrote about the harkening critters compilation for Pitchfork.

Mark Cutler released two albums, Quartus Quærendus and Not Welcome (Themes and Variations), both of which can be found at Bandcamp.

Marshall Gu wrote a review of Sarah Davachi’s The Head As Form’d In The Crier’s Choir for RA.

James Gui wrote a scene report on Kyushu’s underground music scence for Bandcamp. He also wrote an essay on the emergence and interactions between electronic and underground music scenes across Asia for Pitchfork. And for his Ley Lines column at Bandcamp, he wrote about Palestinian music.

Michael Hong wrote an interview feature on babyMINT for NME.

Vincent Jenewein wrote an essay titled Sound Characters: A Prolegomena to a Concept for Soap Ear. He also wrote about Fluxion’s “Pendoulous” for his Substack, Infinite Speeds.

Colin Joyce wrote a review on Félicia Atkinson’s Space as an Instrument for Pitchfork.

Jinhyung Kim wrote an essay titled Meme/Art/Propaganda for a zine to accompany a work by Jack Morillo.

Joshua Minsoo Kim interviewed Jonathan Rosenbaum and Amina Claudine Myers for the Chicago Reader. He also wrote a review of Collaborative Cataloging Japan’s exhibition, Community of Images: Japanese Moving Image Artists in the US, 1960s-1970s, for the Wire. For Crack Magazine, he wrote a retrospective review on Animal Collective’s Sung Tongs.

Sunik Kim wrote an essay titled Proletariat of a Cursed Colony: The Kanto Massacre as Perverse Logic of Capital for Bellona Mag. They also wrote an essay titled The Dark Filter of Sound: Timestretching, Eroticism and Reification for Soap Ear.

Michael McKinney wrote an interview feature on Hassan Abou Alam for DJ Mag. He also interviewed Roomful of Teeth’s Cameron Beauchamp for Passion of the Weiss, and DJ Lag for wav.world.

Jude Noel wrote a review of 2nd Grade’s Scheduled Explosions for Pitchfork. For the same site, he also wrote reviews of Popstar Benny’s Oasis and Tony Vaz’s Pretty Side of the Ugly Life.

Eli Schoop wrote a review on Cindy Lee’s Diamond Jubilee for Bandcamp Daily.

Shy Clara Thompson wrote a review of the Virtual Dreams II: Ambient Explorations in the House & Techno Age, Japan 1993-1999 compilation for Pitchfork.

Evan Welsh co-curated the Just Cause Vol. 1 compilation, whose proceeds go to the Palestine Children’s Relief Fund.

Thank you for reading the 166th issue of Tone Glow. The Writers Panel is back???

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.

TETO